An eloquent preacher during his life, St. Anthony has become one of the Church’s most popular saints.

A favorite in much of the Catholic world, St. Anthony of Padua has more cities and places named after him than any other saint—68. This includes 44 in Latin America, 15 in the United States, four in Canada, four in the Philippines, and one in Spain. Four capes, three bays, two reefs, and two peaks also take his name.

Even more numerous have been, until recently, the statues of St. Anthony in churches, where he is depicted holding the Christ Child, the book of Scriptures, and a lily or a flaming torch.

A Saint with Worldwide Appeal

Anthony must have been a favorite of missionaries who took this likable saint to the Western Hemisphere and to many other lands around the world. But over the years it seems to have been laypeople who have adopted St. Anthony of Padua as a kind of all-purpose saint—finder of lost articles, helper in troubles, healer of bodies and spirits. Hundreds of thousands have prayed the quaint old responsory: “If miracles thou fain would see, Lo, error, death, calamity . . .”

We might be tempted to ask, as a friar once asked St. Francis of Assisi: “Why after you? Why after you?” The answer seems to be both the immense popularity of St. Anthony in his lifetime and the flood of wonders that followed his death.

St. Anthony’s Early Life

Anthony was born in 1195 (13 years after St. Francis) in Lisbon, Portugal, at the mouth of the Tagus River, from which explorers would later sail across the Atlantic. His parents, Martim and Maria de Bulhões, belonged to one of the prominent families of the city and were among those who had been loyal in service to the king. The infant was baptized in the nearby cathedral at the foot of Castelo de São Jorge, which still dominates the city. His parents named him Fernando.

Fernando Martins de Bulhões attended the cathedral school and, at the surprisingly young age of 15, entered the religious order of St. Augustine. “Whoever enters a monastery,” he later wrote, “goes, so to speak, to his grave.” For Fernando, however, the monastery was far from peaceful, because his old friends came to visit so frequently. Their vehement political discussions hardly provided an atmosphere for prayer and study.

After two years of this, the young man asked to move and was sent to Coimbra, 100 miles north. This was the beginning of nine years of intense study, including learning the Augustinian theology that he would later combine with the Franciscan vision. Fernando probably was ordained a priest during this time.

St. Anthony Joins the Franciscans

The life of this young priest took a crucial turn when the bodies of the first five Franciscan martyrs were returned from Morocco. These holy men had preached in the mosque in Seville, almost being martyred at the outset, but the sultan allowed them to pass on to Morocco, where, after continuing to preach Christ despite repeated warnings, they were tortured and beheaded. Now, in the presence of the queen and a huge crowd, their remains were carried in solemn procession to Fernando’s monastery.

Overjoyed and inspired by the martyrs’ heroic deaths, Fernando came to a momentous decision. He went to the little friary the queen had given the Franciscans in Coimbra and said, “Brother, I would gladly put on the habit of your order if you would promise to send me as soon as possible to the land of the Saracens, that I may gain the crown of the holy martyrs.”

After some challenges from the prior of the Augustinians, he was allowed to leave that priory and receive the Franciscan habit, taking the name Anthony, after the patron of their local church and friary, St. Anthony of the Olives. He was allowed to take vows immediately, as the order did not yet require a novitiate.

True to their promise, the friars allowed Anthony to go to Morocco, to be a witness for Christ and possibly a martyr as well. But, as often happens, the gift he wanted to give was not the gift that was to be asked of him. Anthony became seriously ill, and, after several months, he realized he had to go home.

Detour in Italy

He never did arrive home. His ship ran into storms and high winds and was blown east across the Mediterranean. Months later, he arrived on the east coast of Sicily. The friars at nearby Messina, though they didn’t know him, welcomed him and began nursing him back to health. Still ailing, he wanted to attend the great chapter of the Pentecost Mats (so called because the 3,000 friars could not be housed and slept on mats). Francis was there, also sick; however, history does not reveal any meeting between Francis and Anthony.

Since Anthony was from “out of town,” he received no assignment at the meeting, so he asked to go with a provincial superior from northern Italy. “Instruct me in the Franciscan life,” he asked, not mentioning his prior theological training. Now, like Francis, he had his first choice—a life of seclusion and contemplation in a little hermitage near Monte Paolo.

Perhaps we would never have heard of Anthony if he hadn’t gone to an ordination of Dominicans and Franciscans in 1222. As they gathered for a meal afterward, the provincial suggested that one of the friars give a short sermon. Quite typically, everybody respectfully declined. So Anthony was asked to give “just something simple,” since he presumably had no education.

Anthony also demurred but finally began to speak in a simple, artless way. Suddenly, the fire within him became evident. His knowledge was unmistakable, but his holiness was what really impressed everyone there.

St. Anthony Turns to Preaching

Now he was exposed. His quiet life of prayer and penance at the hermitage was exchanged for that of a public preacher. Francis heard of Anthony’s previously hidden gifts, and Anthony was assigned to preach in northern Italy. It was not like preaching around Assisi, where the faith was strong: In the north, he ran into heretics, well organized and ardent.

The problem with many preachers in Anthony’s day was that their lifestyles contrasted sharply with that of the poor people to whom they preached. In our experience, it could be compared to an evangelist arriving at a slum in a Mercedes, delivering a homily from his car, and then speeding off to a vacation resort.

The heresy of that time thus had its grain of truth. The so-called “pure” (Cathari) began by wanting to go back to Gospel poverty. Scandalized by the wealth of the Church, they practiced strict poverty and engaged in manual labor. But they also denied the validity of the hierarchy and the sacraments. They saw themselves as the only “real” Christians.

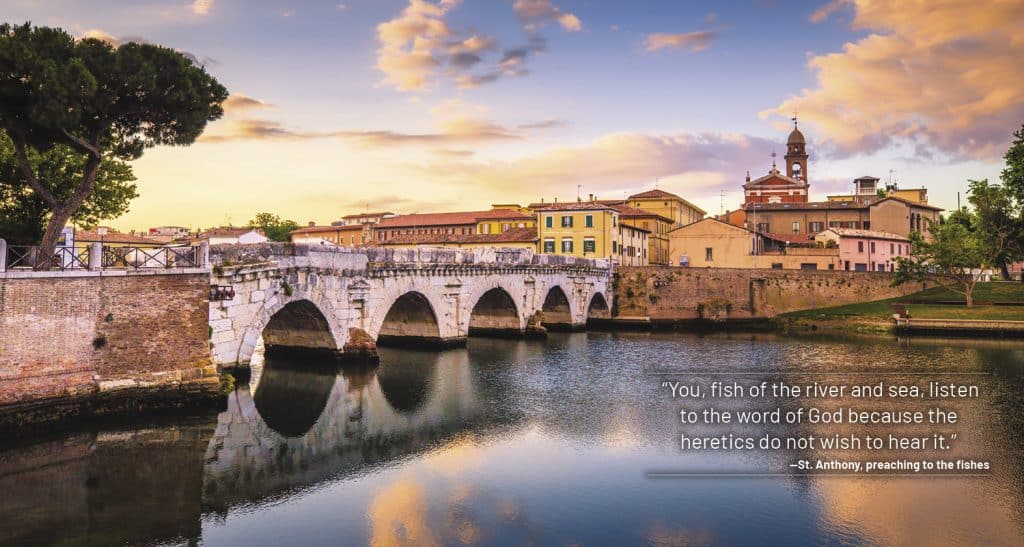

Anthony saw that words were obviously not enough. He had to show the Cathari Gospel poverty. People wanted more than self-disciplined, even penitent, priests. They wanted the unselfish genuineness of Gospel living. And in Anthony they found it. They were moved by who he was more than by what he said. In Rimini, one hotbed of heresy, he was able to call the people together—that alone was a sign of his fame.

Despite his efforts, not everyone listened. Legend has it that one day, while preaching to deaf ears, Anthony went to the river and preached to the fishes. That, says the traditional tale, got everyone’s attention.

Anthony traveled tirelessly in both northern Italy and southern France—perhaps 400 trips—choosing to enter the cities where the heretics were strongest. Yet the sermons he left behind rarely show him taking direct issue with the heretics. As the historian Daniel Clasen interprets it, Anthony preferred to present the grandeur of Christianity in positive ways. It was no good to prove people wrong. Anthony wanted to win them to the right, the healthiness of real sorrow and conversion, the wonder of reconciliation with a loving Father. The word fire recurs in descriptions of him. And though he was called the “Hammer of Heretics,” the word warmth describes him more fully.

Public Preacher, Franciscan Teacher

Anthony’s superior, St. Francis, was cautious about education such as his protégé possessed. He had seen too many theologians taking pride in their sophisticated knowledge. Still, if the friars had to hit the road and preach to all sorts of people, they needed a firm grounding in Scripture and theology. So, when he heard the glowing report of Anthony’s debut at the ordination, Francis wrote in 1224, “It pleases me that you should teach the friars sacred theology, provided that in such studies they do not destroy the spirit of holy prayer and devotedness, as contained in the Rule.”

Anthony first taught in a friary in Bologna. The theology book of the time was the Bible. In one of Anthony’s extant sermons, there are at least 183 passages from Scripture. While none of his theological conferences and discussions were written down, we do have two volumes of his sermons: Sunday Sermons and Feast Day Sermons. His method included much allegory and symbolical explanation of Scripture. Nature was a fertile field from which Anthony gathered symbols and allegories—as did Jesus—such as the lilies of the field, the nest of birds, the web of the spider, the last cry of the dying swan. But above all, Anthony made references to fire, which is why he is sometimes portrayed with a book (the Bible) in one hand and, with the other, holding a flame out toward the onlooker.

On the occasion of St. Anthony being declared a doctor of the Church (January 16, 1946), the minister general of the Friars Minor, Valentine Schaaf, wrote: “Our Holy Doctor was the connecting link which joined the chain of the ancient Augustinian tradition [which Anthony had learned in Coimbra] to the then barely emerging Franciscan school. . . . After Anthony, it was especially the Seraphic Doctor St. Bonaventure and the Venerable John Duns Scotus, the Subtle Doctor, who continued to adhere more rigidly and faithfully to the Augustinian spirit, which is briefly expressed in the following words: ‘The fulfillment and the end of the Law and of all divine Scriptures is love.’ Both unanimously assert that theology is a practical science insofar as it is the end of theology to move and lead man to love God.”

Anthony continued to preach as he taught the friars and assumed more responsibility within the order. In 1226, he was appointed provincial superior of northern Italy, but he still found time for contemplative prayer in a small hermitage. Around Easter in 1228 (he was only 33 years old), he went to Rome, where he met Pope Gregory IX, who had been a faithful friend of and adviser to St. Francis. Naturally, the famous preacher was invited to speak. He did it humbly, as always. The response was so great that to many people it seemed that the miracle of Pentecost was repeated.

Padua Enters the Picture

Padua, Italy, is a short distance west of Venice. At the time of Anthony, it was one of the most important cities in the country, with a university for the study of civil and canon law. Religion there was at a low point. There was constant fighting between the tyrant Ezzelino, a ruthless, brutal man who led the Ghibellines, and the Guelph party in nearby Verona. Anthony divided his time between solitude—to write the two volumes of his sermons—and preaching to the people of Padua. Sometimes he left Padua for greater solitude. He went to a place loved by Francis—Mount La Verna, where Francis received the wounds of Jesus. He also found a grotto near the friary where he could pray in silence and solitude.

In poor health and still serving as provincial superior of northern Italy, he went to the general chapter in Rome and asked to be relieved of his duties. But he was later recalled as part of a special commission to discuss certain matters of the Franciscan Rule with the pope.

Back in Padua, he preached his last and most famous Lenten sermons. The crowds were so great—sometimes 30,000—that the churches could not hold them, so he went into the piazzas or the open fields. People waited all night to hear him. He needed a bodyguard to protect him from the people armed with scissors who wanted to cut off a piece of his habit as a relic. After his morning Mass and sermon, he would hear confessions. This sometimes lasted all day—as did his fasting.

Anthony was instrumental in a matter of social justice. Under the law, a Paduan debtor was put in prison if he could not pay. A new law read: “At the request of the venerable Friar (and holy confessor) Anthony of the Order of Friars Minor, it is established and ordained that henceforth no one is to be held in prison for pecuniary debt.” Debtors did have to relinquish their possessions, but they were free.

In another instance of civic involvement, he failed to move the tyrant Ezzelino to release the leader of those opposing him. Anthony was so disappointed over this that he withdrew from public life.

Last Days and Canonization

The great energy he had expended during Lent left him exhausted. He went to a little town near Padua, but seeing death coming close, he wanted to return to the city that he loved. “If it seems good to you,” he said to one of the friars, “I should like to return to Padua to the friary of Santa Maria, so as not to be a burden to the friars here.” The journey in a wagon weakened him so much, however, that he had to stop at Arcella. He had to bless Padua from a distance, as Francis had blessed Assisi.

At Arcella, Anthony received the last sacraments and sang and prayed with the friars there. When one of them asked Anthony what he was staring at so intently, he answered, “I see my Lord!” He died in peace a short time after that. He was only 36 and had been a Franciscan but 10 years.

The following year, his friend Pope Gregory IX, moved by the many miracles that occurred at Anthony’s tomb, declared him a saint. Many years later, during exhumation of Anthony’s body for transferal, Anthony’s tongue was found to be still lifelike and of a natural color, though the rest of his body had disintegrated. St. Bonaventure, head of all Franciscans in the world, was present at the transfer, and he cried out: “O blessed tongue, you have always praised the Lord and led others to praise him! Now we can clearly see how great indeed have been your merits before God!”

Anthony was a simple, humble friar who preached the good news lovingly and with fearless courage. The youth whom his fellow friars thought was uneducated became one of the great preachers and theologians of his day. He was a man of great penance and apostolic zeal. But he was primarily a saint of the people.

3 thoughts on “Who Was St. Anthony?”

My mother would always take us to St. Antony’s Church on Tuesdays.

When I was 14 years old, she bought me a prayer book from which I used to say a prayer to St. Antony to ask for simple things one after the other and surprisingly it was always granted. He has all along, heard my prayers. I’m now 77 years and recently when my daughter -in-law found her wedding ring missing, St. Antony found it for her in the most unlikely place.

Thank you St. Antony .

When I was a child, our Mother taught us to pray to Saint Anthony if we lost something. I can not tell you how many things have been found after praying to him, wedding ring recently. Now nearly 70 years old, I have fond memories of my dear Mother telling us stories about the Saints and teaching us our prayers.

Where are our saints of today? Pope Francis, Mother Teresa, Padre Pio? I guess it takes time for us to appreciate them and St. Francis and St Anthony are today.

Comments are closed.