This parish-based agency in Chicago offers hope to those jailed in both body and spirit.

Seventeen-year-old Jaime Chavez swaggers into the agency living room as if he owns it. Wearing a bulky jacket and a loose-fitting shirt, he moves with a confidence indicative of a modern teenager. With a wide smile and a shiny earring, Jaime’s trendy exterior is belied by his reserved, humble voice. He is, in many ways, the typical American teenager.

But Jaime has lived in a place that is miles from typical. On two different occasions, Jaime spent a month in the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center in Chicago, Illinois, for gun possession. Stripped of his belongings, separated from his family and sharing space with strangers, Jaime edged dangerously close to being a seasoned regular at the Cook County Detention Center.

“It’s definitely not cool,” he says, “knowing that you won’t be going home the next day. The first time I went in there, it was bad. The second time I figured, ‘What am I doing here?’ I saw myself coming in and out of places like that. I didn’t want to end up in jail.”

Sustaining Jaime through his ordeals were a rejuvenated faith, a flair for poetic self-expression and hope for a life better than the one he was living. Backing him were the people of Kolbe House—the Chicago Archdiocese’s prison and jail ministry.

The Healing House

Jaime is just one of thousands, on both sides of the prison walls, who have been rescued by the more than 40 workers and volunteers of Kolbe House. Located just two blocks from Cook County Jail, Kolbe House is an inconspicuous building that rests in the heart of a restless neighborhood.

Dangerous and diverse, manic and multicultural, this busy area seems anchored by Assumption Parish, headquarters of Kolbe House and its prison missionaries. It’s an engaging place. Though it is not a halfway house, it has the feel of a well-lived-in home. And like many homes, it’s bustling with footsteps and voices of workers breezing in and out of assorted rooms. This is a home with a frenzied family-staff. This is an agency on a mission.

It was named after St. Maximilian Kolbe, the Polish Conventual Franciscan who was imprisoned in Auschwitz and murdered in 1941. Kolbe House—the only agency of the Archdiocese of Chicago that deals directly with inmates—started in 1983 to reach people whose lives have been damaged by crime. The agency and its workers labor with the same drive and selfless abandon as the martyred saint.

It’s been an uphill battle from day one. Starting with no operating budget and existing primarily through donations, Kolbe House has stayed afloat even when financial cutbacks and wavering fiscal support threatened to sink it. Kolbe House workers have pressed on in their mission to offer spiritual liberation to the physically captive and help to restore their beleaguered humanity.

By offering Masses, religious services, spiritual counseling and Bible study, workers and volunteers offer a refuge to the incarcerated. Simply being present in the jails affords inmates a much-needed—and often missing—lifeline.

Father Arturo Pérez-Rodríguez came to Kolbe House in 2003. He believes that providing these essentials is vital to inmates’ lives and to their faith journeys. “I love this because it’s direct ministry. It’s important to just be with these people without judgment of them,” he says. “We take these people for who they are and where they are at. We offer a spiritual grounding for their lives.”

Father Arturo has experienced divine moments inside Cook County Jail. God’s grace, he believes, is found in all corners of the facility. “There’s a real sense of the presence of God in their lives,” he says. “It’s exciting for me in the way that they talk so openly about faith. For me it’s quite inspiring.”

Mending the Broken People

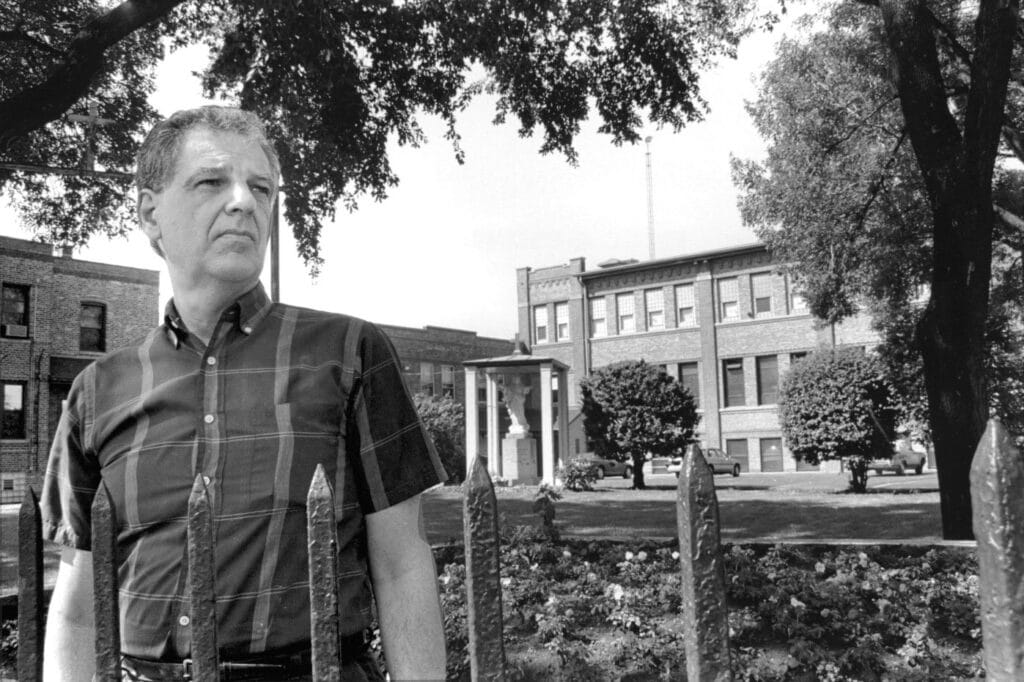

Father Larry Craig, director of Kolbe House since 1983 and pastor of Assumption Parish, has been the agency’s driving force from the beginning. Working in prison ministry for 37 years, Father Larry has seen it all: bureaucracy at its ugliest, inmates at their weakest, families inching toward emotional and financial ruin, and the faith that sustains them all. Looking more like a philosophy professor than a priest, Father Larry is a tall, imposing man with forceful eyes, shrouded in a mane of silver hair. When speaking about the thousands of men, women and children he and his team have aided, his posture softens.

“The Church believes that we’re all part of the body of Christ, and that body needs all of its members,” he says. Acting as a voice for those whose own voices are often ignored, Father Larry and his staff seek to heal the wounds of prisoners. In their often-tattered faces, this priest sees the face of God.

“God becomes human in relationship to other humans,” he says. “That’s where we uniquely experience God and that’s where hope and conversion become a support for life.” Along with aiding in matters of the soul, Kolbe House helps in matters of physical survival as well.

To the recently released—as well as the families of those doing time—support often comes in the form of money for rent, heat or electric bills, clothing or food. Sometimes parolees simply crave a sense of belonging.

“We hope that people who are isolated or alienated feel welcomed back,” Father Larry says. “People who are released from prison can be rescued. They can feel like they belong.”

Making a career out of helping to mend broken people, Father Larry handles inmates and their families with compassionate candor and a listening heart. “We know where they’re coming from so we try to jump right in and say, ‘O.K., this is what I think is happening here. Now let’s see what we can do about it.’”

A Harsh Sentence

Chicago resident Dino Pavlis has had the good fortune to be on the receiving end of Kolbe House’s assistance. Married to Irma for 10 years, Dino has watched as his wife endures inside Cook County Jail for the last 17 months. Since she has yet to stand trial, Dino, who is Catholic, cannot discuss her case.

What he is open to discuss is the emotional wreckage with which he struggles every day. Dino’s association with Kolbe House, as well as Irma’s relationship with Gilda Wagner—one of the agency’s part-time prison chaplains—has helped to ease the sting of separation between husband and wife. Sharing space with more than 40 other inmates, Irma, 33, must navigate through a claustrophobic and sometimes dangerous environment. She finds peace through her weekly visits with Gilda. These visitations provide the inmate with a gentle, human closeness, something Dino can no longer provide.

“When I visit, I can’t even touch my wife’s hand because of the glass,” he says. “What helps me is that I know there’s somebody to visit Irma on a regular basis and who brings the Eucharist. For my wife, who’s very Catholic, the Church provides a physical presence.”

Inside prison walls, kindness is elusive, from inmates as well as guards. “Not all the guards are bad but, as a general rule, they have this grouchy factor,” Dino says with a smile. “And of course she’s dealing with aggression from the other inmates.” Dino says his wife survives the routine of prison life by reading in private and attending Bible study groups and prayer services. Latching on to a small cluster of other Catholic inmates also helps. In a caged life, Irma’s faith is her great escape.

“Celebrating a weekly Mass is very important to her,” he says. “It gives Irma a spiritual base and allows her to transcend her physical realities.” For Dino, support groups hosted by Kolbe House help to ease his own realities. Irma, in the end, isn’t the only one serving time: Dino is also locked away in his own prison. If jail is punishment for the convicted and the accused, then the penalty of waiting and living without is handed out to the families. Dino is all too aware of his own harsh sentence.

“I’m barely surviving this, but I’m O.K.,” he says. “I take great comfort in Kolbe House.” Befriending the Friendless Comfort is a luxury rarely afforded anyone rocked by crime and punishment.

Perhaps the place where comfort is most needed is death row. The long arm of Kolbe House extends there, too.

Charles Walker was a murderer. In the summer of 1983, Walker—drunk and in search of cash—approached Kevin Paule and Sharon Winker as they fished at Silver Creek near Mascoutah, Illinois. Tying the couple to a tree, Walker shot them both in the head and walked away with $40. Convicted and sentenced to death, Walker came to know Deacon Ron DeRose from Kolbe House. Deacon Ron—a volunteer since 1988 and fulltime chaplain since 1995—began a spiritual mentorship with Walker. In his jovial voice, Deacon Ron remembers fondly his experiences with the death-row inmate.

“It was wonderful to be able to pray with him, to be able to hold his hand as the last hours, the last minutes of his life ticked away,” he says. “We laughed, we cried, we prayed. Charles had made his peace with God.”

After refusing to move forward with his appeals, Walker welcomed death. On September 12, 1990, he was executed at Stateville Correctional Center. Deacon Ron—along with Deacon George Brooks, director of advocacy for Kolbe House—has seen the range of grief that haunts the inmates of death row. Weathered by the memories, Ron still looks back on his experiences with a peace-filled heart.

“All I can say is that there were holy moments. It’s been a wonderful journey through the last 10 years. I’ve had some wonderful, colorful, spiritually moving experiences,” the deacon says. “Being with people at that moment when they, in their brokenness, reach up a hand to God—it’s been awesome. I found people who were truly repentant for what they had done.”

What Deacon Ron has kept close to his mind and heart is something many cannot acknowledge: These jailed men and women, guilty or innocent, are still of value. “These inmates are in a system that takes away their dignity, their sense of self,” he says. “We help them to understand that they still are somebody.”

Starting Over

Jaime Chavez is proof of that. While serving time in the Juvenile Detention Center, Jaime happened across Making Choices—a Kolbe House published newsletter of poetry and artwork created by those in and out of jail. Filled with candid prose and illustrations, the publication was a creative endeavor that guided the young poet out of a shadowy place.

Unbeknownst to Jaime, salvation lay hidden in the pages. “I read the Making Choices newsletter on the inside, and it got me interested in what Kolbe House was doing,” he says. Jaime began attending Masses and poetry workshops while serving time in the detention center. After he was released for the second time, Jaime saw an opportunity to begin again.

“I came to the Making Choices group once I was released,” he says. “Kolbe House got me interested in school and then helped me to enroll. Now I am in my first year of college.” Jaime Chavez, once a high school dropout with a criminal past, has reinvented himself. The people of Kolbe House—who helped Jaime obtain his G.E.D.—were a main ingredient in that reinvention. But his work with them isn’t over. For this young student, an ongoing involvement with the agency is an essential factor to his success.

“They keep asking me about school. They help me when I don’t understand something, like registering for classes,” Jaime says. “It keeps me motivated and gives me people to talk to. Also I feel I can’t do things wrong because if I do, I’ll disappoint them. They care.”

To Rescue and Heal

It may seem like thankless work: counseling criminals, advocating for those condemned to die, helping their families. On the contrary, for the workers of Kolbe House, this is their calling: a grace-filled opportunity to rescue and heal. And they have learned as many lessons as they have imparted.

Father Arturo is often astounded at the inner strength that many prisoners have. ”I’m amazed at the peace that some people are able to have at spending 30 years in jail,” he says. “They know what they’re going to confront. They’re fearful about what they are going to confront but they’re grounded.”

Deacon Ron has been equally moved by those he has encountered in his ministry. Even in the most desolate of places, grace abounds. “I find God is working very powerfully behind those walls. The strength of faith that I see in some of these people is genuine,” the deacon says. “Anytime a person’s life is in crisis, the future is uncertain and the present seems unbearable—those are the times when people reach out to God.”

In the heart of an often-depraved environment like a maximum-security prison, thousands of inmates over the last two decades have sought healing and forgiveness, companionship and compassion. Kolbe House workers have been there to witness it all.

What began as a dream in the spring of 1982 is now a blessing to the many who toil behind bars. The people of Kolbe House journey into the darkest of places—armed with patience and eager hearts—all working in the spirit of the biblical passage: “When I was in prison, you visited me.”

And Restorative Justice for All

The wide arms of Kolbe House embrace all those rocked by crime. Though their primary focus is support for the incarcerated, Father Larry Craig and his team advocate for victims as well. “We do in fact minister to victims of crime and their families,” he says. “We continue to be concerned about the accused, victims, those who work in the system, etc.”

Kolbe House favors restorative justice, which is healing the wounds of victims, offenders and communities that have been damaged by crime.

“We are, of course, very interested in restorative justice—whatever it takes to restore the balance between humans,” Father Larry says. “We give food, clothing and referrals to whomever comes to our door. Our pastoral counseling extends to all such people.”

Father David Kelly, C.Pp.S., who works at Kolbe House part-time, helps at the Precious Blood Ministry for Reconciliation in Chicago. Father Kelly works with families of the imprisoned as well as victims of crime. He is also involved in initiatives on the juvenile level that are related to restorative justice. Deacon George Brooks, director of advocacy for Kolbe House, also tackles this issue on a legislative level.

Though Kolbe House aids both victims and perpetrators, Father Larry believes that, on many occasions, only a fine line separates the two. “There are very few, if any, ‘good guys’ or ‘bad guys’ in the world,” he says. “Everything is a bit gray. Most of the detainees themselves have been victims of crime at some point in their lives.”

Learn more about Kolbe House here.