In the spirit of St. Francis, this retreat center opens its doors to refugees.

Driving up the long, steep hill from Danville, California—escaping the congestion of the town and the roar of I-680—one who sees the first sign for San Damiano retreat center breathes a sigh of relief. What a far more welcoming sight the friary, with its graceful Spanish architecture, must be to a refugee who hasn’t had a permanent home in 17 years!

The story of Franciscans housing refugees intertwines the three Abrahamic religions—Christianity, Islam, and Judaism—in stunning harmony. It echoes St. Francis‘ experience of Islam. And it offers small steps toward answering the larger question of refugees confronting the United States and the world.

A Refuge of a Different Kind

San Damiano’s red tile roof and white walls surround a courtyard filled with fountains and flowers native to California. It’s easy to see how the place has become an oasis for retreatants seeking prayerful beauty and calm.

But if, as some believe, the retreat business is dying, what’s the future for this and centers like it? Or, as Franciscan Brother Mike Minton, the center’s director from 2015 to 2016, asks, “How do we become something the world needs?”

His community considered several possibilities suited to its mission of being “a Franciscan presence in northern California. ” Since 1961, the friars of the St. Barbara Province have made the 55-acre site “a peaceful environment of natural beauty where spiritual renewal and growth may be sought by people of all faiths and backgrounds.”

The friars have sought to build on that foundation.

For example, the Franciscans’ commitment to care for creation has led them to offer a 12-session course in permaculture, a method of sustainable farming based on natural ecosystems. Trying to offer winter shelter to the homeless proved impractical, however. So the discussion evolved to, “Whom can we help? Maybe refugees?” When Brother Mike saw an ad in a local paper requesting housing, it seemed a perfect fit. He exclaimed, “We’ve got 80 bedrooms!”

Meanwhile, Amy Weiss was losing sleep in her role as director of refugee and immigrant services at the nearby Jewish Family and Community Services East Bay. Because real estate prices in the area have skyrocketed, she had nowhere to house the influx of refugees. Her umbrella agency, HIAS (formerly called the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society), is the oldest of the nine resettlement agencies in the United States. “We do this work not because we’re resettling Jewish people, but because we are Jewish people, ” says Weiss, echoing the ancient tradition of hospitality that Jews practice because they know the migrant experience firsthand: “‘My father was a refugee Aramean who went down to Egypt with a small household and lived there as a resident alien'” (Dt 26:5).

In a partnership that might seem improbable, she welcomed the Franciscans’ offer of emergency and transitional housing. This “love at first sight” led to ongoing collaboration: she has placed nine men at the retreat center who have stayed for periods of three weeks to seven months. The relationship remains fluid: depending on what’s happening at San Damiano, the friars must sometimes say no or ask for a brief delay.

A Place of Safety and Hope

The collaboration began two months before Pope Francis, in September 2015, asked every convent and monastery in Europe to house refugees. It isn’t always idyllic: some guests have quarreled over the washing machine and cleanup, or the timing of meals. Mistrust and suspicion have arisen because of religious differences. A retreatant fearfully warned Brother Mike, “There’s an Arab with a backpack in the courtyard!” But, as he says, “A Franciscan place should be able to take people who are at odds and bring them together.” Grinning, he adds, “Pax et bonum [‘Peace and good’] is the bumper sticker; with human beings, it’s always a process.

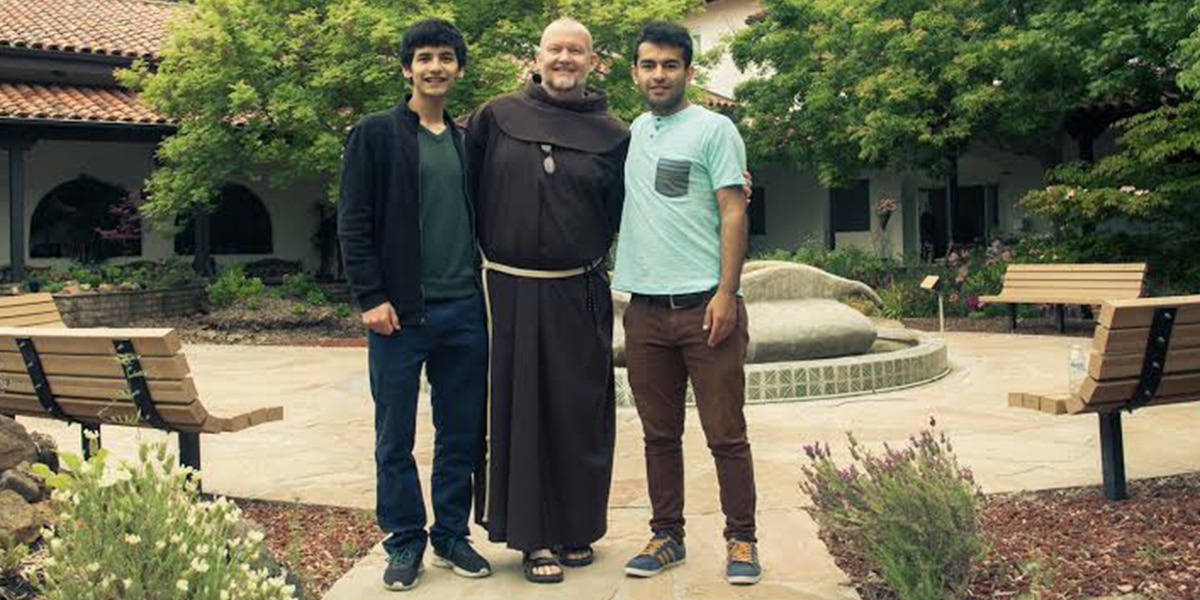

Brother Mike asks only that refugees define goals and work toward them. While it’s tempting to linger indefinitely, they must shape their futures in a new country and move forward. For example, Jalal, 21, says, “Here I have a dream and freedom.” He wants to be a chef; his brother Kamal, 20, studies computer science. They hope to bring the rest of their family here, just as another refugee brought his wife and five children to the United States.

Originally residents of Afghanistan, the brothers’ family was targeted by the Taliban because their father served in the army. Leaving when Jalal was 4, they fled through five different countries. The family finally arrived in Russia, but without legal status there, they could not be schooled or employed. The San Damiano friars were deeply touched by a Nativity scene that these Muslim brothers painted and gave them at Christmas dinner.

The screening process to enter the United States is intense and can take years. While waiting in refugee camps, undocumented refugees face formidable obstacles, many stemming from language barriers and cultural differences. Often, they are pumped with adrenaline for the process, but can finally calm down at San Damiano.

The relief in the voice of a Ugandan reaching San Damiano is palpable: “This is the only place in my life I’ve been fed without expectations.” Those who come as families or friends move on more quickly; those without rely more heavily on the Franciscans for emotional support. Those who have sustained serious psychological damage can receive pastoral counseling. Some mask wounds or avoid memories too painful to confront.

When an employee saw a resident lifting a laptop high and low around the grounds, she thought he was searching for a signal and explained that he could get Wi-Fi in his room. The boy replied, “I’m Skyping with my mom. I just want her to see how safe I am. “

Many Faiths, One Human Family

Brother Mike speaks for the San Damiano community: “When we first thought about doing this, it seemed like we were doing a really good thing. But what I’ve discovered is that our refugees have called us to the best humanity we can be. God created humans, not religions. Now we all stand bigger, fuller, and better within our own traditions.”

He refers to the joint effort: Episcopalians arrange transportation and free haircuts, Mormons donate from their food banks, and Muslims give clothes. A Methodist minister who had been making a retreat at the center met the refugees and donated money toward their expenses.

Two weeks later, she e-mailed that her congregation had prayed for Catholic Franciscans, in partnership with a Jewish agency, helping Middle Easterners of various religious backgrounds. Given the incentive of vulnerable need, humans can move past their divisions.

While only about half the refugees are Muslim, Brother Mike has a long-standing interest in Islam. He prays at the mosque on Fridays, fasts for part of Ramadan, and has taken close to 300 Christians to visit the mosque, helping them wrestle with their feelings about Islam. Long engaged in Muslim-Christian dialogue, he hosted 90 people for a retreat where each religion learned about the other “branch of the family” and prayed together. As Islamic scholar Dr. Nazeer Ahmed said: “Coming together in the spiritual domain has huge effects. It’s like opening a second window into the infinite vastness, seeing the beauty of creation not only through the inner eye of our own tradition, but also through the other’s.”

St. Francis and the Sultan

Brother Mike’s hospitality places him squarely within the lineage of St. Francis. Nothing in Francis’ culture would have prepared him to think Muslims might be good. The emphasis then was on killing the infidel to serve Christ. Popes offered the promise of heaven to Crusaders who would “cleanse” the Holy Land of the evil “enemy.” Francis went along on the Fifth Crusade in 1219 and crossed the battlefield to speak with Malik al-Kamil, the sultan of Egypt.

Scholars disagree on exactly what motivated Francis to go initially or stay and visit, but evidence is clear that the experience affected him profoundly. The two leaders who tried at first to convert each other grew in appreciation that each already loved and revered God. In an atmosphere of violent hatred, Francis, the man of peace, tried—and failed—to stop the Crusaders from attacking the Muslims at the Battle of Damietta.

His willingness to cross the battlefield parallels an earlier experience, to which Francis attributed his conversion: embracing the leper. In his day, lepers had ashes spread on their heads, their funerals were held with their families present, and then they were banished outside the city walls, forced to cry the chilling word unclean. For Francis to hug the leper meant embracing the other; there he found “that which had before seemed bitter was now changed for me into sweetness of soul and body.”

It’s possible the same thing happened with the sultan. After their time together, when Francis was steeped in Islam, the effects showed in his prayer. When he told people to fall to the ground in adoration, he must have remembered the posture Muslims take five times a day. When he savors God as light, mercy, compassion, and forgiveness, he seems to echo Islam’s “99 Beautiful Names for God.”

“Be at home,” Brother Mike said almost casually to visitors. What depth his words must carry to those who have not had a home for so long. G.K. Chesterton wrote, “St. Francis walked the world like the pardon of God.” Perhaps at San Damiano, he continues to walk one corner of this world in a similar style.