Both the US government and the Catholic Church had a hand in the establishment and operation of Native American boarding schools, where, for nearly a century, thousands of children were sent without their parents’ consent. Now religious congregations across the country are finding out about their own involvement and working toward repairing shattered relationships with Indigenous communities.

When I was growing up, I remember experiencing Indigenous culture firsthand and feeling so enriched and excited by it. For many years, my family has spent vacations in northern Ontario at a cabin along one of the many lakes that dot the Great Lakes region. Ultimately, it was love that brought my family in close contact with the Ojibwe people and culture: My oldest brother dated and later married a woman from the nearby Mississauga First Nation Indian Reserve (what would be called a reservation in the United States).

The first powwow I attended was unforgettable. I remember hearing the sound of the pulsing drumbeat and traditional chants from the parking lot and being filled with wonder and even a bit of trepidation. At 11 years old, I was in for a deep plunge of cultural immersion that day, as I ate the food, listened to the swirling chants, and soaked in the colors of the traditional clothing worn by dancers in the powwow circle. Years later, on return trips up north, I started noticing signs along the highway that passes through two Ojibwe reserves, including my sister-in-law’s, on the way to our family cabin. Signs that read “Protect Our Children” and “Every Child Matters” alluded to something dark and sinister, but I wasn’t sure what was at the bottom of these messages.

The more I read about the origin of these roadside signs, the more I found out how widespread and pernicious were the abuses that took place in Canada’s residential schools. As truth and reconciliation efforts have made strides in our neighbor to the north, more information has come to light about the reality here in the United States at what were called Native American (or Indian) boarding schools. That our Indigenous brothers and sisters suffered abuses at the boarding schools—some of which were Catholic-run—is a profound injustice in need of repair.

Native communities, which have absorbed enormous intergenerational trauma, are currently walking the long road to healing. Thanks to their resilience and willingness to do the hard work of restorative justice with allies in the Church, though, there is hope for a brighter future. But before true healing can happen, it’s important to understand what caused this trauma and why it still has so much impact today.

Not Ancient History

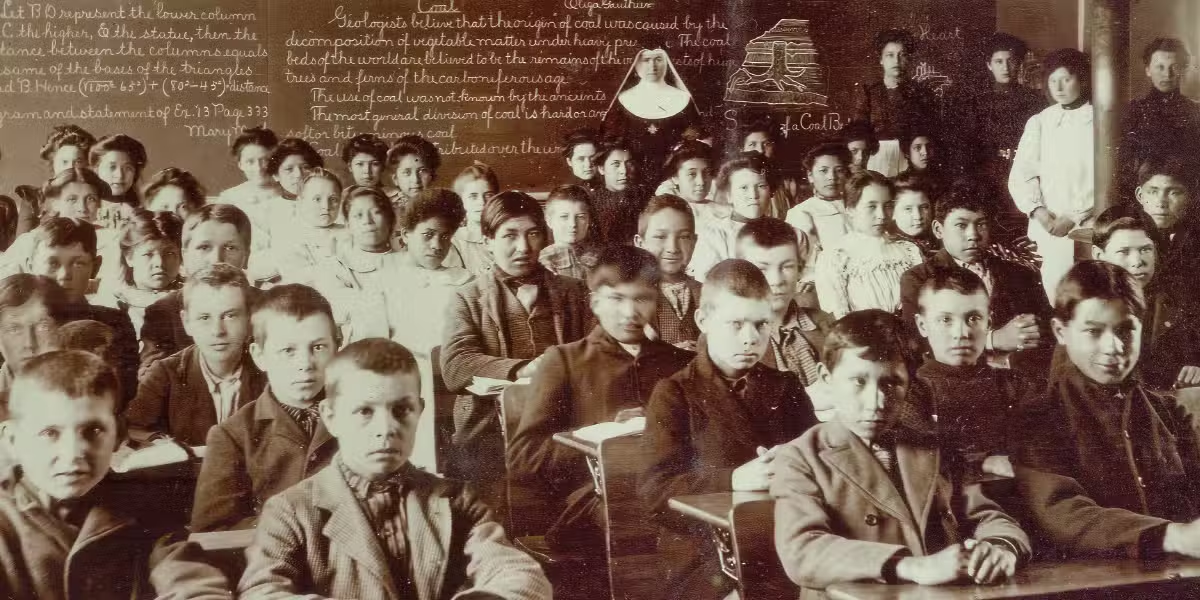

In the 1880s, and under the guise of providing Native children with a proper education and instilling in them American values, the boarding school system took shape. After many were forced onto reservations, Native families sustained further trauma as children were taken from their parents without consent and often with the threat of violence or legal repercussions should they refuse. According to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS), 523 boarding schools operated at various times in the United States, and, by 1926, there were nearly 61,000 Native children in the schools, which existed in 38 states and impacted Alaskan and Hawaiian Indigenous peoples as well. That comes out to about 86 percent of all Native school-age children in the United States at the time. If this sounds like ancient history, consider the fact that the system of boarding schools continued through the 1960s. Legislation passed by Congress in 1978 finally put the power of consent back in the hands of parents.

There were a number of ways that boarding schools set out to wipe Native identity from the minds and spirits of children, including cutting boys’ hair (which would typically only happen upon the death of a tribal elder), giving students Anglicized names, and prohibiting students from speaking their language or practicing their spirituality. Richard Henry Pratt, an American military officer and one of the early proponents of the boarding school system, once infamously summed up the government’s approach: “Kill the Indian, and save the man.” In 2021, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland (an Indigenous woman herself) launched a federal investigation, with the results revealing that physical, sexual, and emotional abuse were rife at these institutions.

Officially, over 500 children died at various boarding schools in the United States, although that number is sure to grow as more research is done. Both marked and unmarked burial sites have been identified at 53 different schools. The report notes, “Federal records indicate that the United States viewed official disruption to the Indian family unit as part of Federal Indian policy to assimilate Indian children.”

When collective trauma, stemming from actions such as the US government’s assimilation policy, continues to have a negative impact over time, it becomes intergenerational trauma. It’s often manifested in any number of social ills, from increased incidences of substance abuse to unemployment to suicide. According to the Centers for Disease Control, non-Hispanic Indigenous people die by suicide at a rate higher than any other racial or ethnic group. A 2020 American Community Survey, conducted by the US Census Bureau, showed that one in three Native Americans lives in poverty, with a median income of $23,000.

A Time to Listen

But what does all of this have to do with the Catholic Church in America? Alongside efforts by NABS, an organization called Catholic Truth & Healing

(https://ctah.ArchivistsACWR.org) has attempted to catalog all of the Catholic-run boarding schools, a daunting task. The group started compiling the list of schools in 2021, and though the current number of Catholic-run schools listed is 87, it’s expected to grow as more information comes to light. Congregations of Catholic women religious ran 74 of the Catholic boarding schools, and some of those groups are just now finding out about their involvement.

The Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration (FSPA), located in La Crosse, Wisconsin, is one such group with ties to a boarding school and is still very much in the process of discovery, archiving, and working toward healing. A page on the FSPA website dedicated to truth and reconciliation states: “We’re studying our own history and impact at St. Mary’s Boarding School in Odanah, Wisconsin, from 1883 to 1969. Our hope is that we take action in dismantling systemic racism and White supremacy in ourselves and our areas of influence. Our intention is to address our complicity in unjust systems, both historically and now, and strive to enhance dignity and wholeness to those who have suffered for generations.”

The congregation’s vice president, Sister Georgia Christensen, FSPA, is passionate about this justice issue and committed to the painful but essential process of healing. “Educating ourselves is the first step,” she says. “We’ve attended webinars and had book discussions. We’ve participated in powwows, and we’ve done two walks for missing and murdered Indigenous women [Known as MMIW walks, these events help to raise awareness.]. We provide justice training for our own people and, in fact, just completed a training session for 50 of our members and staff. It was very intense—a three-day workshop where we set up peace circles.”

A major part of the education piece is deceivingly simple and not as easy as it sounds: listening. For a people whose history has been told largely by its colonizers, it’s incredibly important that the power to own and share their history be returned to them. To this end, the FSPA’s Truth and Healing Team has participated in listening sessions, where members of the Ho-Chunk and Chippewa/Ojibwe nations speak about the traumas experienced at St. Mary’s, as well as the effects of intergenerational trauma. The result of these listening sessions has been a positive step for both parties.

“It’s relationship-building that is working toward providing us the opportunity to say we’re sorry and we want to do something that will work toward healing,” Sister Georgia says. “I think one of the biggest things for us is really to develop relationships. When we started our Truth and Healing Team, we had sisters, affiliates, partners in mission (our staff), and we had an Ojibwe member on the team.” The team has since expanded to include a member from the Ho-Chunk Nation, a man who Sister Georgia says has been “extremely helpful and challenging, which is exactly what we need.”

Documenting a Collective Trauma

Coupled with the education piece is the painstaking but crucial task of archiving the FSPA history with the St. Mary’s Boarding School. This is important work for the congregation’s own understanding of its past, but even more so for the Ojibwe and Ho-Chunk people. The archives have been opened and made available to them, which helps families track down information on their connection to St. Mary’s Boarding School.

FSPA archivist Meg Paulino shares a particularly impactful moment that occurred as she was reading through some correspondence between the school and a Native American family. In the letters, she noticed that a 12-year-old boy had been sent back home to his family due to illness. A notice in a local newspaper reported that the boy had died, but the names didn’t match up. “I looked through all our record books and couldn’t find him there,” she says. Frustrated, Paulino dug deeper into the story. “Finally, I went to, of all things, FindaGrave.com,” Paulino recalls. “I just went deep into it. I was going to find this young man.” She discovered that the boy had a younger brother who was also at the boarding school. The records show that the younger brother remained at St. Mary’s after his brother was sent home. He would never see his older brother again.

“This was one of the first times [working in the archives] I broke down crying,” says Paulino, who, being a mother of young boys herself, deeply related to this story. “This one really hit me hard, and it made me realize how important it is to help people find their ancestors and loved ones. It’s a very small part of my job in the archives, but I drop everything when it comes to finding out what happened to children such as this boy.” Paulino was able to share everything she found out with the boy’s family, giving them a sense of closure they wouldn’t have had otherwise. Along with sharing documents and correspondence with nearby Indigenous communities, the FSPA Truth and Healing team has returned cultural items and artifacts to the Bad River Chippewa Tribe in what was called a “repatriation ceremony.”

Apologies Need Action

Quickly offered, shallow apologies for egregious wrongs are commonplace today, which is something the FSPAs want to avoid. Educating themselves on and transparently documenting the FSPA history at St. Mary’s Boarding School must come before an apology. “It’s a learning process,” says Sister Georgia. “I think the apology gets woven into it. You don’t start with it.”

As similar efforts are underway at numerous congregations and orders across the country to bring about justice and reconciliation, we, as Catholics and Americans, have to face up to what amounts to an act of genocide. Many of those who work closely on the issue of boarding schools in the United States watched intently as Pope Francis made what he called a “penitential pilgrimage” to Canada in 2022. In his address to a group of Indigenous leaders in Maskwacis, Alberta, he stated: “I am here because the first step of my penitential pilgrimage among you is that of again asking forgiveness, of telling you once more that I am deeply sorry. Sorry for the ways in which, regrettably, many Christians supported the colonizing mentality of the powers that oppressed the Indigenous peoples. I am sorry.”

During his July 2022 visit to Maskwacis, Alberta, Pope Francis prays in front of a banner bearing the names of 4,120 Indigenous children and the residential school where they died. Truth and healing efforts are currently underway in the United States.

As monumental as Pope Francis’ visit to Canada was, it set the stage for more work to be done. Finally, on March 30, 2023, the Vatican officially repudiated the Doctrine of Discovery, which for over 500 years had justified the colonization of Indigenous peoples, land seizures, and the myriad human rights abuses that followed. All but four of the Native American boarding schools in the United States have closed, and those that remain are firmly in the hands of the Indigenous people who run them and send their children there—this time, by choice. Unlike the Canadian government, which issued an official apology to Indigenous peoples and formed a Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2008, our own government has yet to do either. In fact, the word genocide is nowhere to be found in official reports, such as the Department of the Interior’s 2021 investigation.

The work of the FSPA Truth and Healing Team, NABS, and many others helps ensure that, by studying and accepting the hard truths of history, we’re not doomed to repeat the same mistakes. For Sister Georgia, these efforts are deeply rooted in the Franciscan charism. “I see it as a part of simple, honest living and getting back to creation,” she says. “Trying to live the Gospel was what St. Francis tried to do, and I think that’s what we’re trying to do.”

In their own ways, often unseen by many, these groups are continuing to respond to God’s directive to St. Francis at San Damiano: “Francis, go and repair my house, which, as you see, is falling into ruin.” Those on a mission to address our country’s sad history of Native American boarding schools are placing a stone back in the San Damiano Chapel and rebuilding God’s house. “Maybe it’s bigger than a stone,” says Sister Georgia. “It’s a huge effort.”

Additional Resources

• Information on the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration’s truth and healing efforts: FSPA.org/content/ministries/justice-peace/truth-and-healing

• The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition: BoardingSchoolHealing.org

• “Healing with Our Indigenous Brothers and Sisters,” an article by Adrienne Castellon on Canada’s residential schools (St. Anthony Messenger, November/December 2023): FranciscanMedia.org/st-anthony-messenger/healing-with-our-indigenous-brothers-and-sisters

• The United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention (which includes its definition of genocide): UN.org/en/GenocidePrevention

• The US Conference of Catholic Bishops Subcommittee of Native American Affairs: USCCB.org/committees/native-american-affairs

2 thoughts on “Trauma and Truth: Native American Boarding Schools ”

The British writer Nigel Biggar has written a book on this subject titled: “Colonialism, A Moral Reckoning,” copyright 2023. I thought the book was informative. He mentions the mass graves of Indians in Canada, but the causes of those deaths are not what some people have come to imagine.

Which are the four remaining Native American boarding schools, and how can I support them?