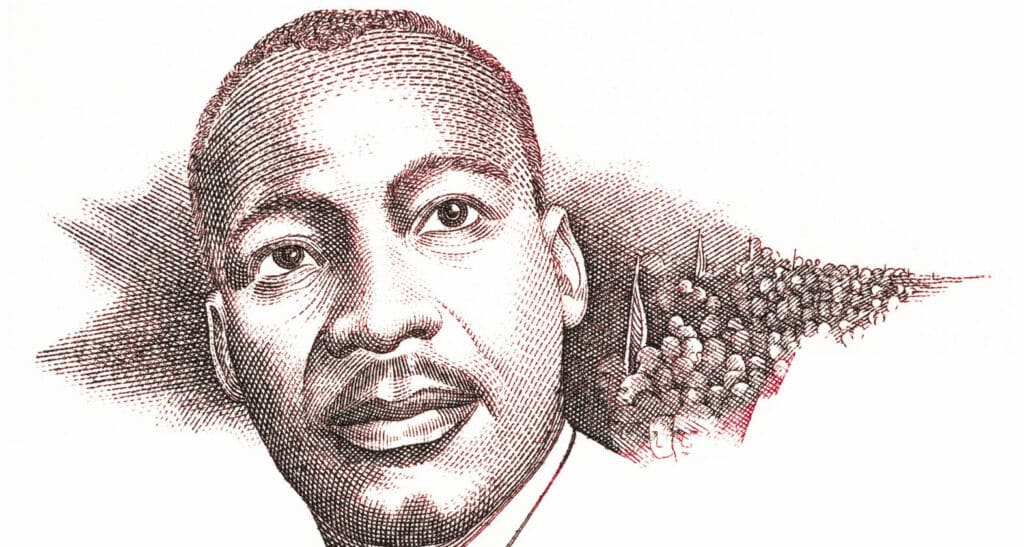

What do an American civil rights icon of the 1960s and an Italian mystic from the 13th century have in common? More than you might think.

In a 2021 letter to the Rev. Bernice King, daughter of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Pope Francis wrote, “In today’s world, which increasingly faces the challenges of social injustice, division, and conflict that hinder the realization of the common good, Dr. King’s dream of harmony and equality for all people, attained through nonviolent and peaceful means, remains ever timely.”

This wasn’t lip service to a fallen American icon. At his talk before the United States Congress in 2015, Pope Francis singled out Dr. King—along with Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton, and President Abraham Lincoln—as ideal representations of the American people.

Born the son of a preacher and a choir director on January 15, 1929, Dr. King championed civil rights for Americans of color through nonviolent means until his assassination in April 1968. An American civil rights activist and an itinerate 13th-century Italian mystic might have little in common, but the spiritual principles laid by Francis of Assisi 800 years ago clearly took root in Dr. King’s mission.

As we celebrate his life and his life’s work in January, these famous quotes show an uncanny understanding of the Franciscan spirit.

“Darkness cannot drive out darkness: only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate: only love can do that.” Dr. King drew upon Matthew 5:43–45 when he gave his “Loving Your Enemies” sermon in 1957 in Montgomery, Alabama, but much of it could have been written by Francis himself. The civil rights movement was in motion by then, and Black Americans faced mounting aggression.

In fact, even after the Civil Rights Act was signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson in 1964, people of color faced poll taxes, literacy tests, and other forms of psychological or physical intimidation. But Dr. King insisted on social change through nonviolent protest.

In his own time, St. Francis of Assisi saw political unrest and a brutal caste system. Born into a family of means, he shed his wealth for a life of radical simplicity, for which he would be known. But he was a saint with a tireless capacity for love as well: love of the natural world and all its inhabitants. And with that, he recommended that his early brothers go into the world with the same interminable love.

“The friars are bound to love one another because our Lord says, ‘This is my commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you’ (Jn 15:12). And they must prove their love by deeds, as St. John says: ‘Let us not love in word, neither with the tongue, but in deed and in truth’” (1 Jn 3:18).

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” While Dr. King was incarcerated in April 1963, he penned his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” And though he never deviated from the path of nonviolent resistance, he could, at times, lose patience when he was met with resistance—even among fellow clergymen. Dr. King was a prophet, not a saint.

Though the central theme of the letter is about countering racial injustice with love, Dr. King covers a lot of bases in 7,000 words. He rails against the civic lethargy of Black clergy as well as White clergy who “stand on the sideline and mouth pious irrelevancies and sanctimonious trivialities.” He also reminds us that God is the true keeper of history. Grace will always side with the righteous.

In recognizing injustice, he had a kindred spirit in St. Francis. In the valley just below Assisi, lepers were kept out by city walls, and those who suffered from the disease rang bells to make their presence known. One major step in Francis’ conversion was his meeting with a leper on the side of the road. Rather than recoil, he embraced him. From then on, he lived his life in solidarity with those on the periphery.

He recalled the incident, writing: “When I was in sin, the sight of lepers nauseated me beyond measure; but then God himself led me into their company, and I had pity on them. When I had once become acquainted with them, what had previously nauseated me became a source of spiritual and physical consolation for me. After that, I did not wait long before leaving the world.”

“We must learn to live together as brothers or perish together as fools.” Dr. King employed several tactics to both further his mission for Black Americans while also dismantling White separatism. Among them was religion. In a 1964 speech in St. Louis, Dr. King reminded us that division among races isn’t just immoral. It’s unholy. As a preacher, he would rely on his religious acumen to remind Americans that we are all imperfect children of a perfect God—essential members of one body of Christ.

There is scriptural support for that position. The Gospels are awash with references to the unity of God’s human family. “So we, though many, are one body in Christ and individually parts of one another” (Rom 12:5) is but one example.

On the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in August 1963, when King gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, he longed for a day when “the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.” Historians differ on whether that dream was realized.

Centuries before, as Francis of Assisi lay dying, he prayed that his early followers would continue his mission but always lead with love. All roads, he understood, begin and end there. “Because I am not able to speak much because of my weakness and the pain of my illness, I make known briefly my will and intention to all my brothers present and future,” he said. “Namely, that as a sign that they remember me, my blessing, and my testament, they always love one another as I have loved them and do love them.”

“We must accept finite disappointment, but never lose infinite hope.” Dr. King had reason to despair—and behind closed doors, he might have. But he kept a brave face in public. This quote from February 1968 illustrates a kind of hopeful realism with the civil rights struggle: Battles are often lost, though the war will surely be won.

Hope, in fact, was the bedrock of his work. “If you lose hope, somehow you lose the vitality that keeps moving,” he said that same year. Two months later, he would be murdered in Memphis. A kindred spirit, St. Francis drew strength from one source: God. As his order grew and became unwieldy, Francis sought solitude to pray, yet he understood that he wasn’t, ultimately, in charge. This must have given him a measure of hope.

“Be my rock of refuge, a stronghold to give me safety,” he wrote. “For you are my hope, O Lord. On you I depend from birth; from my mother’s womb you are my strength; constant has been my hope in you.”

“Life’s most persistent and urgent question is: What are you doing for others?” In this century of excess, could we give up all material comforts and live among the poor? It was just as unthinkable in Francis’ day. Nevertheless, he shed his worldliness and embraced Lady Poverty, “a fairer bride than any of you have ever seen,” he told a childhood friend.

To renounce his father’s wealth and live among the poorest was not only an act of defiance against his inheritance, but an act of charity fueled by grace. Solidarity with the poor, for Francis, was an act of love. He coached his brothers to do the same: “And to this poverty, my beloved brothers, you must cling with all your heart, and wish never to have anything else under heaven.”

Though a true intellectual, Dr. King kept his words and his ideals grounded in everyday Christian principles. He was a son of God first, a citizen of the country second. Therefore, Gospel-infused charity was the true heartbeat of his beliefs. He wrote and spoke widely about not only political inequality in America but also the country’s need to end poverty, illiteracy, racial violence, and exclusion. Nobody should be refused a seat at the table.

The questions Dr. King asked his audience in that Montgomery, Alabama, speech in 1957 still resonate: What are we doing for the least of us? How are we bettering the lives of others? In what ways can we work for justice, to counter hate with love, to work for peace?

Decades later, he awaits an answer.

Sidebar: The Pope and the Preacher

When Pope Francis spoke before Congress during his US visit in 2015, he highlighted four people who symbolized the best of what the country has offered the greater world: Dorothy Day, who embodied a spirit of service; Thomas Merton, whose spiritual hunger governed his life; President Abraham Lincoln, the great defender of liberty; and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., a champion of equality.

Pope Francis praised the slain civil rights leader for daring people of color in this country to dream big. “That dream continues to inspire us all. I am happy that America continues to be, for many, a land of ‘dreams,’” he said. “Dreams which lead to action, to participation, to commitment. Dreams which awaken what is deepest and truest in the life of a people.”

Could the pope give such a speech today before our two bitterly divided political parties? Would his words be dismissed as “woke”? In that speech he called Americans to our better angels—as the 16th president did—and to rise to the challenge of loving those on the margins.

Pope Francis closed his speech with: “It is my desire that this spirit continue to develop and grow, so that as many young people as possible can inherit and dwell in a land which has inspired so many people to dream. God bless America!”

4 thoughts on “The Franciscan Spirit of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.”

Dr King showed the country that change can happen through non-violent resistance. I appreciate the parallels drawn here between Dr. King and Saint Francis of Assisi. Both men have much to show us—especially now with Ukraine and Gaza—in kindness and compassion towards others. God send us more prophets of peace. Pax.

Thank you for this look at two great men centuries apart but joined by a shared mission to spread peace. Amen

Beautiful writing. Pray for peace. 🕊️

Gorgeous. Thank you to the Franciscans for this analysis. 🙏