This wife and mother wanted to model her life on Dorothy Day’s. But she quickly learned that hospitality begins in the heart, not the home.

I wanted to be Dorothy Day long before I’d ever heard of her.

As a teenager, I was volunteering in an assisted-living home while my peers were hanging out in shopping malls; as a college student I was doing internships in African orphanages and mentoring at-risk kids in my community. For as long as I can remember, my heartbeat has sounded like impact, impact, impact—whether from pure altruism or my own pride, I have often debated. But whatever the motivation, I’ve long bristled at the idea of wasting my time on earth.

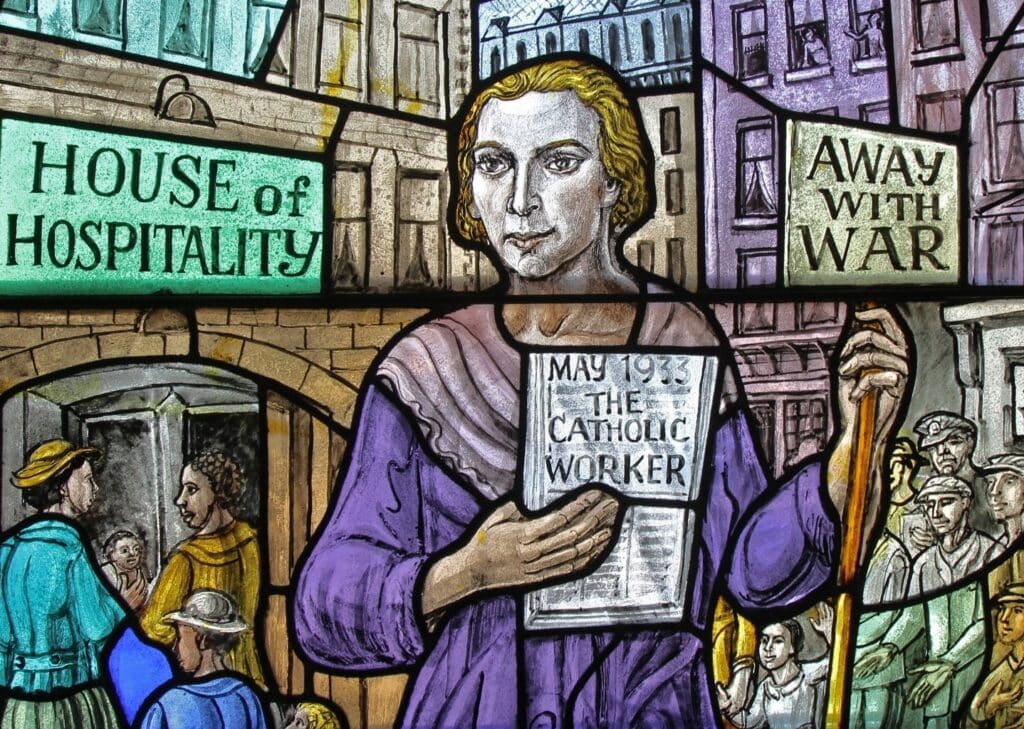

Around the time I married my husband at a green 23 years old, he introduced me to Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker Movement—both of which I heartily approved, as though the world were anxiously awaiting my assessment. But I didn’t give her much further thought until we began researching Catholic social teaching before our Confirmation into the Church years later. As most who have done so can tell you, you can’t dig far into the social doctrine of the Catholic Church without clinking your spade against this stalwart woman. Our involvement with a local Catholic Worker only solidified my admiration, and Day’s lens of solidarity and hospitality began to deeply form my emerging worldview.

A Reality Check

When Kate Hennessy’s book Dorothy Day: The World Will Be Saved by Beauty came out last year, I snatched up the chance to explore the more intimate world of Day’s, certain that her granddaughter could provide me with the keys to unlocking the predicament of how to live the radical life I felt called to, even as a mother of young children. Alas, I found no magic formulas or mystical insights: Dorothy Day, it seems, struggled to balance her dual vocations of mother and justice advocate as much as anyone. Sometimes she got the balance right; often she got it wrong.

The book evoked a bit of controversy among Day devotees, some disappointed by their heroine’s maternal shortcomings and others dismayed by the perceived agenda of the non-Catholic author. I thought it was more or less both a tender and fair portrait. People are complex, and saints are no exception.

But the real intrigue of the story was Tamar, Day’s only daughter from her common-law marriage to Forster Batterham. Tamar and her husband, David Hennessy, had nine children and struggled to make ends meet. For reasons that remained a bit mystifying, Day discouraged Tamar from making her home at the Catholic Worker, despite Tamar’s apparent desire to do so.

At the time of my reading of The World Will Be Saved by Beauty, my husband and I were preparing to move our family of five (with one on the way, I was surprised to find out) to start a house of hospitality with a friend. Although reading about the ideals of Dorothy Day, Peter Maurin, and the Catholic Worker Movement at that particular time in my life was inspiring, the effect on Day and Tamar’s family life was sobering—not least of all because I so fiercely wanted to protect the well-being of my own children.

When a Dream Dies

A few months in, it became clear that our family wasn’t well suited for the Catholic Worker life. For the second time that summer, we packed up our children and all our belongings. We went home. The grief I felt was tremendous; a grieving not just of one failed house of hospitality, but of everything I had thought my life would be. The past decade had been one disillusionment after another, and with this final nail in the coffin I mourned the woman I once thought I was.

I couldn’t stop thinking about Tamar.

Her life, I feel certain, did not turn out the way she had once imagined as a child swept up in the love and kinship of the Worker. The Hennessy family struggled through poverty, unfruitful farming, hyperfertility, loss of faith, and a strained marriage; and while the Catholic Worker network provided Tamar with lifelong friends and support, most of her days were spent alone in her home.

“You have a house of hospitality,” Day would remind her adult daughter, pointing to Tamar’s nine children as well as the neighborhood kids and other visitors she routinely welcomed into her surely cramped home. While author Kate Hennessy’s documentation of her granny’s encouragement comes across as a brusque write-off of Tamar’s desire to reintegrate into the Worker, I can’t help but read the words differently.

When we moved back home after the debacle of a house of hospitality attempt, there was no doubt in my mind that it was the right thing to do. Yet it felt like a death to me—a necessary one, sure, but a death all the same. Weeks after returning, I wept to my spiritual director about the pain of such dying. She looked at me, bemused, and gently asked, “Why do you call it a death?”

Maybe she hadn’t understood the part about crucifying my dreams for the sake of my family. Maybe she hadn’t been listening as I’d detailed the image of what my former 20-something self had imagined her life to be; maybe she wasn’t clear on how far from that ideal I was destined to live. It was the death of a dream. Wasn’t it?

Rising from the Ashes

I left that appointment and drove straight to a spiritual retreat, where one of our assigned exercises was to read the story of Lazarus and pray over what God wanted to tell us through it. Angry at the Holy Spirit for having the gall to make such an assignment, I huffed my way through John 11 until I heard the still, small voice like a punch in the gut: “What looks like death is not the end. What looks like death is a chance for truer life.”

As I write these words, it has now been nine months since our hopes burned down and we began rebuilding from the ashes—nine months, the gestation of human life. We moved back to a different house in the same city—this one serendipitously placed in a small collision of socioeconomic structures.

Here at the literal corner between daffodil window boxes and subsidized housing, we sit as bridge builders and peacemakers. We didn’t choose this house; this house chose us. It bade me walk across its creaky floors with a cup of coffee to contemplate hospitality.

Day had a house of hospitality; we all know that. And we rightly revere her for it. But Tamar had one too, even if her mother was the only soul to recognize it. Tamar welcomed children as Jesus himself once did—her own, yes, but also those of other women, their lanky limbs running through her kitchen on hot summer days. She welcomed the lonely when she herself was so dreadfully lonesome. Tamar didn’t feed hundreds, but she fed a few. Her doubting heart may not have believed she was offering the bread of life, but the few ate and were nourished. Where is Christ if not in that?

I admit I still idolize Dorothy Day; part of me still wishes I were more like her. I doubt that will ever change. But as the days roll by, I find myself thinking more about Tamar. I think about the sacrifices she made for her husband and children, how dutifully and silently she tried to do the right thing. I think about how she wrestled with God and doubt, how she suffered interpersonally without the temperament to express her needs. I admire her strength and I pity her frailty, just as I do my own.

Children of all ages, races, and wealth are jumping on the trampoline in the backyard. I can hear their squeals of delight as I type. I’ll talk with mothers later on in the heat of the day—we’ll talk about the garden, we’ll talk about racial injustice, we’ll eat cantaloupe, and we’ll live this fruitful, painful, mundane life together, side by side.

I don’t think this kind of house of hospitality—Tamar’s kind—will ever look or feel important. But I do think it will matter. And I think Dorothy Day would say it does too.

The Little Way of Dorothy Day

by Joel Schorn

Dorothy Day looked to St. Therese of Lisieux for guidance in her day-to-day life with the Catholic Worker. She even invoked Therese as a kind of patron saint of their work: “We should look to St. Therese, the Little Flower, to walk her little way, her way of love.” Dorothy also believed that the answer to violence and the destruction of modern war lay with little Therese, whose tuberculosis-wracked body had been resting in its grave for half a century when Dorothy wrote, “On the frail battleground of her flesh was fought the wars of today.”

The little way is the way of peace, Dorothy believed. “Paperwork, cleaning the house, dealing with the innumerable visitors who come all through the day, answering the phone, keeping patience and acting intelligently, which is to find some meaning in all that happens—these things, too, are the works of peace, and often seem like a very little way.” We can see the importance of finding meaning in everything that happens, of seeing the presence of God in all people and things, but how could Dorothy describe these tasks as “works of peace”? How could such a huge problem as the violence in the world find itself laid at the door of a house of hospitality? What did she mean when she said, “In these days of fear and trembling of what man has wrought on earth in destructiveness and hate, Therese is the saint we need”?

For Dorothy Day, the small acts of mercy the Catholic Worker practiced opened the road to peace, for the way of peace is a little way. “Year upon year of serving meals, making beds, cleaning, and conversing with destitute, outcast people,” Catholic Worker historian James Allaire wrote, “provided Dorothy with ‘schooling’ in the Little Way. Added to this daily routine were her writing and publishing the Catholic Worker newspaper, speaking around the country, praying, fasting, protesting, and enduring jail on behalf of peace and justice.

“The Little Way is the way of Gospel nonviolence because it invites us to love one another as Jesus loved us (Jn 13:34), an unrestricted love that brings mercy and compassion to all people. Jesus’ nonviolent love extended even to giving his life in redemptive suffering on the cross.”