Two close friends of St. Oscar Romero Latin American saint have a conversation about his life and love for the Salvadoran people.

On March 24, 2015, thousands of Salvadoran Catholics and people from other parts of the world gathered in the capital of El Salvador, San Salvador, for the 35th anniversary of the death of Archbishop Oscar Romero. Two months later, on May 23, another transcendent—and perhaps the most important—event in the modern history of El Salvador occurred: Archbishop Oscar Romero, martyr of the Catholic Church, was beatified, thus becoming the first Blessed of El Salvador. His canonization is set to take place on October 14 in Rome.

I returned to my country for this significant anniversary and met the auxiliary bishop of the Archdiocese of San Salvador, Jos é Gregorio Rosa Chavez. We had both lived in community with Romero in the late 1970s. Rosa Chavez was the rector of the San Jos é de la Montaña Central Seminary in San Salvador in 1977—the same year that Romero was appointed archbishop of the archdiocese.

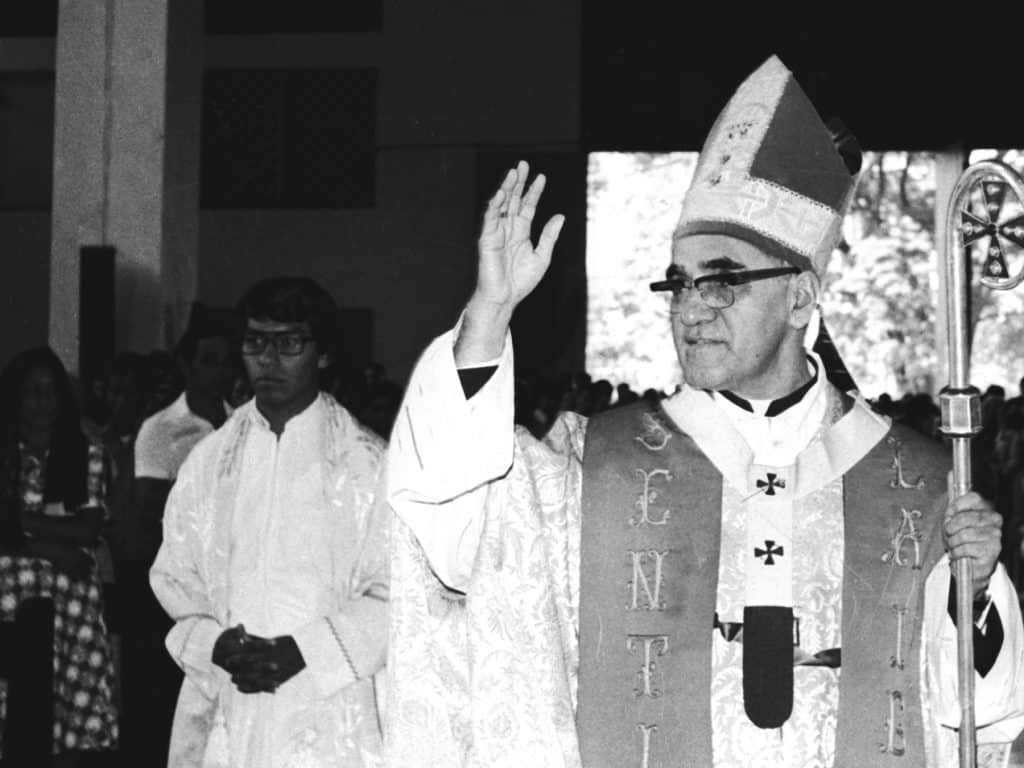

Romero lived for a short time in the seminary where I was a seminarian. During that time, I accompanied him on his trips through the Salvadoran towns and had the opportunity to photograph him with his people. Rosa Chavez was the cohost of a radio program, Sentir con la Iglesia (To Feel with the Church). In a way, both of us were inspired by Romero to live our vocation to the Church through the media.

The following is my interview with Bishop Jos é Gregorio Rosa Chavez, just prior to Romero’s May 2015 beatification.

Oscar Romero, A Look Back

People ask me what Romero was like. But it is difficult for me to answer accurately. For me, he was a human being who surrendered himself to god and his people. But back then, when I met him, I did not realize the true dimension of the man and what he now means for the world. Could you tell me about the human side of Romero?

He was reserved, a person of few words, discreet, timid, introspective, thoughtful, often worried, sometimes fearful, sometimes hesitant. That’s how you and I knew him. Romero was also a man of strong character but in a humane way. No one would dare stop him on the way to church for his personal prayers. He enjoyed being with simple people. He did not like being with the important people because he saw a lot of hypocrisy in them.

He was very demanding of himself and of others. He was scrupulous about not offending the Lord. Some of his internal conflicts had to do with his character. That was one of the crosses he carried but, in the end, managed to overcome when he realized the love his people had for him.

When Father Octavio Ortiz Luna [a Salvadoran Catholic priest] was killed [on January 20, 1979], we all went to the funeral Mass. People surrounded the bishops, and Romero uttered a beautiful statement: “How well people respond when we know how to love them.” At that point, he felt very much embraced by the people.

On a theological level, I understood the meaning of being embraced by people; there is a kind of reciprocal affection and commitment. That is very much the tone given by Pope Francis when he says that one must be a shepherd with the “smell of the sheep.”

At the international level, Romero advocated a dynamic change in a preference for the poor. Was he radical, or was it simply that he had always had that sentiment for the poor in his heart?

One Wednesday, I interviewed him and asked him, “They say that you have been converted; what do you think of that?” And he said, “I would say that it is not a conversion but an evolution.” When he was the bishop in another diocese, he saw reality in a different way. Then he arrived here, saw the reality of ingrained injustice, and realized that he had to accompany the people in denouncing the injustice. He was attentive to what God was asking of him.

In the Diocese of San Miguel, it was a quiet, nonthreatening atmosphere, and suddenly here he encounters all the injustice of military, economic, and political power that massacred people. So he had to respond to that reality.

There is another question that was posed: “Aren’t you afraid that they will kill you?” His answer: “I’m not afraid, but apprehensive. God goes with me, and, if something happens to me, I am willing.”

That enduring sense of martyrdom linked to his ministry ran throughout his time in San Salvador.

Martyr, Man of God

Romero is a martyr for faith. What is the significance of that?

The case of Romero marks a stage in Church [history] regarding martyrdom that highlights the position of the Vatican on the model of pastor. Romero was a product of the Second Vatican Council; he is a model of the pastoral thrust of the council. His ministry also reflects the world Synod of Bishops in“Pastores Gregis” [an apostolic exhortation by St. John Paul II], where the profile of the bishop is described: to be pastor of the poor, fighter for justice, defender of the weak, a prophet who denounces. When one reads the document, one could easily say that profile describes Romero.

Romero’s death is martyrdom for the faith. It wasn’t the typical martyrdom [brought on] by pagans. People who called themselves Christians killed him, people who went to Mass on Sundays and received Communion; that is unusual.

How can that be explained?

Romero was killed because he followed Jesus Christ in his choice for the poor, for justice, for human dignity, for a more dignified life for all, which is what the Church demands today. So that is a recent rationale for the argument that makes theologians say that he is a martyr of the Church. In the doctrine of the Church, this marks a novelty and an advance. There are many cases like this, so they will now be understood as martyrdom.

Thirty-five years ago, you wrote a symbolic letter to Romero after his death, in which you gave a general idea of how the people were doing. If you were to write it again, what would you say?

Yes, I remember that letter. I wrote it a month after his murder. In it, I told him that people were going to put flowers at his tomb, that we felt as if he were still among us, that the problems in the country continued, that the people needed hope, and that his words were very alive in their hearts. It was a letter that came out of my heart. Yesterday, at the anniversary memorial, we could see Romero still present on the lips of people—believers and nonbelievers.

Romero is an interesting phenomenon. A journalist was asking me if we would forget his legacy over time. Note that it doesn’t work like that with him. Usually as time goes by, you forget people who have died. Here it is the opposite; more and more people know and love him. And what will happen on May 23 is that we are going to see a saint, a saint who impacts the whole world.

Those feelings are the same today. There are still people carrying flowers to his grave, and there are problems in the country. There is a lack of hope. Why doesn’t the situation in El Salvador change?

I have also been asked why the process of canonization took so long. For 20 years, we had the same government guiding the country, one that rejected all that Romero had done, who never spoke well of him. One slogan that the people chanted during the Saturday Mass was: “If Romero is holy, why did it take so long?” One reason was that the government did not support this process and did not let it proceed. This same mind-set hindered a solution for the roots of the crisis that led to the civil war. It was a structural crisis of injustice, inequity, and exclusion.

That was the tone for 20 years. Then the gap widened, and the poor became poorer and the rich became richer. Mauricio Funes arrived in 2009, changed direction, and emphasized social progress. So now Romero was resurrected in the public discourse. That’s how we arrived at the current government, which took a step closer to national dialogue and created an autonomous council, in which all are represented. Romero was killed because he followed Jesus Christ in his choice for the poor, for justice, for human dignity.

And there I am with three other representatives of the Catholic Church. An action plan has been developed with goals, budget, international assistance, and a period of five years for implementation. We are entering a new stage in the history of the country, and the world is aware of this. There is worldwide sympathy within the United Nations and the European Union for this initiative.

We did not have this before, but now we have broad international support, and there is optimism that we are going to take off.

What has been the prophetic role of the church after the death of Romero?

There is a growing self-awareness in the Latin American Church. After the 1979 General Conference of the Latin American Episcopacy and Caribbean (CELAM) in Puebla, Mexico, the Latin American Church missed the opportunity to emerge as a force for justice, as if disinterested in the world it had to serve. Hence, its prophetic role was diminishing.

But then the more recent 2007 CELAM in Aparecida, Brazil, brought back that fervor. And there was also Jorge Bergoglio, the current pope, who as a cardinal coordinated the team that drafted the final document. That connection gave his pontificate the link to the Church’s role in history as a prophetic Church, and that is why Pope Francis has so much affection for Romero.

There is so much similarity in both [men]. The magazine New Life of Spain published an article where I compared the two of them in seven points. For Pope Francis, Romero incorporates what he wants for the Church and for the world.

What would these seven points be?

Marian devotion, so deep in both; shepherds with the smell of sheep; a Church for the poor and with the poor; a vision for a missionary Church that proclaims the paschal mystery; seeing in the poor the flesh of Christ; a Church that is present in the world as yeast, as light and salt. Finally, both evangelize as they are, what they do, and with what they say.

The Good Shepherd

The similarity between both shepherds is amazing. Since you knew Romero so personally as the rector of the seminary, what was your personal experience with him?

You know, when he was named archbishop, I was just beginning in the seminary. That same month and year, we were reopening it after it had been closed during a period of crisis. We removed cobwebs, cleaned, swept, mopped; it was like a building ruined. Romero arrived, and he asks, “Do you have a little space for me to stay?”

So we prepared an apartment for him. He lived with us for several months in his quarters, where he set up his office. It was there that he started something interesting, the radio program Sentir con la Iglesia, broadcast on Wednesdays. He was the host. There were two microphones, and we talked with each other about issues regarding the Church and the country.

I was already familiar with his method of communication from the time when I was an adolescent seminarian. When he had been in San Miguel before that, he had a radio show that was called Oracian de la Mañana (Morning Prayer). One day, we ate dinner together as we were listening to Vatican Radio, and Romero said to me, “Let’s go to the sacristy after dinner.”

There [in the sacristy] was his recording equipment, and he was getting ready to record his radio program. I was standing by, listening to what he was saying, when he suddenly said, “I have next to me a seminarian by the name of Gregorio Rosa, who will say a few words.”

He gave me the microphone without any prior warning, so I improvised a few words. He continued recording, and at the end he said, “That turned out very nicely.” I remember that phrase very well; it was the beginning of my vocation as a communicator. He was passionate about the radio. This shy man who we met with those human limitations became a prophet of the people in front of the microphone. There the spirit of God moved him.

If you read his diary, this topic [of the radio program] appears almost every day: What if the radio program was ruined? What if it was sabotaged? What if the program did not go well or didn’t air? The radio would always be on his mind. One time, they [the Salvadoran government] almost blew up the radio [station], and he uttered this famous phrase, “Even if we lost our radio station, each one of us must become the microphone of God.”

The Ongoing Legacy of Oscar Romero

Oscar Romero Oscar Romero Oscar Romero Oscar Romero Oscar Romero Oscar Romero Oscar Romero Oscar Romero Oscar Romero Oscar Romero Oscar Romero Oscar Romero Oscar Romero Oscar Romero Oscar Romero Oscar Romero Oscar Romero Oscar Romero

4 thoughts on “Oscar Romero: Pastor, Peacemaker, Saint”

Father Romero is a Great Saint. I pray that more of us, laypeople and clergy, emulate his dedication to work of the Good LORD

I simply don’t understand humans inhumanity to other humans! It seems to me we keep repeating history since the beginning. What’s wrong with us?

Father Oscar Romero is a vibrant yet humble martyr that is an inspiration for the people of the United States at this time. Speak Truth to power-with love of the people.

Oscar Romero expanded the dimensions of the ways the church in the modern era could respond to the church. He paid attention to what priests were doing for the poor and opposed persecutions of those priests and the poor even when it was done by people who went to mass and recieved communion. The church has to have a preference for the poor not for the rich and powerful even if the powerful claim to be Catholic. It must insist the powerful love the poor, love justice and do not abuse their power.