A quiet leader, Pope Paul VI guided the Church through the sweeping and controversial reforms of the Second Vatican Council during turbulent times.

Pope Paul VI, despite his enormous impact on the Church—the most obvious being the reform of the liturgy brought about by the Second Vatican Council—is curiously obscure to many Americans. He is perhaps best known for his 1968 encyclical “Humanae Vitae” (“Of Human Life”), which upheld the Church’s controversial ban on the use of artificial birth control.

Paul VI has the disadvantage of being sandwiched between two far more charismatic personalities: Pope John XXIII and Pope John Paul II (elected after Pope John Paul I’s monthlong reign). His was often the unglamorous work of a bureaucrat, not of a beloved papa figure like John or a superstar evangelist like John Paul II. But as the man charged with implementing an enormously controversial council and shepherding the Church in its transition to facing the modern world as a renewed evangelistic force, he faced titanic challenges with intelligence, resolve, and deep holiness.

Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini was born on September 26, 1897, the last pope born in the 19th century. He was ordained in 1920, became a bishop in 1954, and was named a cardinal in 1958. He was a cleric groomed for the papacy by his work in the Vatican, serving in the Secretariat of State (1922–54) and witnessing the torments of what was arguably the most violent century in history.

At the pope’s request, from 1939 to 1947, Montini created an office that worked to find over 11 million displaced persons and provide refugees with shelter, food, and other material assistance. In addition, he helped escaped Allied POWs, Jews, anti-Fascists, Socialists, Communists, and others. It gave him a unique perspective and skill set for the work to which God would call him when Pope John XXIII died in the summer of 1963, having convened the Second Vatican Council in October 1962.

John XXIII initially hoped the council would be able to finish its work by December 1962, after a single two-month session. Montini, with a more realistic grasp of the immense challenges facing the Church, remarked of his friend wryly, “This old boy does not know what a hornets’ nest he is stirring up.”

As pope, Paul VI accomplished so much that it is difficult to summarize in a mere 2,500 words. His biographer, Peter Hebblethwaite, gives a reasonable assessment of his crowded papal career (stretching from June 1963 to August 1978) with these words:

“He managed to complete the council without dividing the Church. He reformed the Roman Curia without alienating it. He introduced collegiality without ever letting it undermine his papal office. He practiced ecumenism without impairing Catholic identity. He had an Ostpolitik [way of negotiating with Communists] that involved neither surrender nor bouncing aggressivity. He was ‘open to the world’ without ever being its dupe. He pulled off the most difficult trick of all: combining openness with fidelity.”

Shepherd of Vatican II

Pope Paul’s most obvious achievement was, of course, to shepherd the Church through the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), the largest rethink of its tradition since the Council of Trent, 400 years earlier. He understood, better than most, that the paradigms that had governed the Church’s engagement with the world since the 16th century were no longer sufficient.

This did not mean that the Gospel was inadequate, of course. But it did mean that the Church needed to return to the sources of its tradition—particularly the Scriptures and the Fathers of the Church—and approach the world with a view not of defending a fortress under assault, but of proclaiming good news as the early Church had done.

Paul VI understood that the Church needed to proclaim the faith with a unified voice, an irony given the hostility the council would meet. The priorities he laid out for the council were a better understanding of the Church, Church reforms, advancing the unity of Christianity, and dialogue with the world. He requested the council fathers to avoid new dogmatic definitions and to restate the faith in simple language.

For Catholics born before 1960, perhaps the most notable change was in the liturgy. Priests faced the congregation instead of the altar and spoke in the vernacular instead of Latin, and laypeople were encouraged to take a more active role in worship.

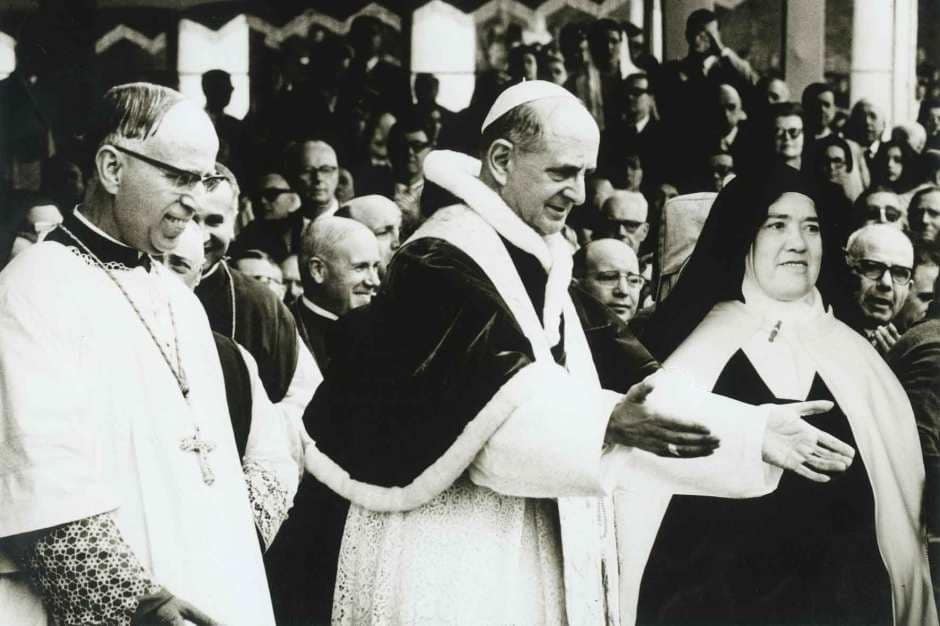

Pope Paul VI was also notably solicitous of the goodwill of the representatives of other Christian traditions at the council, sought their forgiveness for the sins of Catholics that had contributed to the disunity of Christendom, and took particular care to remind the council that many bishops could not attend because they lived under Communist rule. He understood that Christians now stood together in a world that both desperately needed the Gospel and presented the Church with a host of threats that it could not afford to meet with internecine squabbles.

Catholic Ecumenist

Pope Paul VI sought to affirm whatever could be affirmed in common with those from other faith traditions. “Unitatis Redintegratio” (“Decree on Ecumenism”) and “Nostra Aetate” (“Declaration on the Relationship of the Church to Non-Christian Religions”) are the two great models for this approach. Compare them with the documents of the Council of Trent, and the immense shift in tone is plain. Trent reveals the mind of an embattled Church, struggling to condemn one false proposition after another in the heat of combat with the Reformation.

At Vatican II, under Paul VI’s guidance, the Church emphatically shifts to a glass-half-full approach to other Christian traditions and to religious traditions beyond the Christian sphere. Again and again, the Church, while not papering over the real differences between the Catholic communion and other traditions, focuses on what can be affirmed in common.

As a result, Pope Paul made unprecedented strides in healing some of the Church’s ancient and open wounds. For instance, his meeting with Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras I in Jerusalem led to rescinding the excommunications of the Great Schism of 1054. Similarly, after nearly 2,000 years of what had amounted to monologue (and countless shameful persecutions by Christians culminating in the horrors of the Shoah) he inaugurated respectful interreligious dialogue with various representatives of the Jewish people, as well as conversations with other religious traditions, both Christian and non-Christian.

Globe-Trotting Evangelist

Paul VI took his name in honor of St. Paul and, like his namesake, was driven by an evangelistic imperative that governed everything he did. Indeed, he declared in “Evangelii Nuntiandi ” (“On Evangelization in the Modern World”): “Evangelizing is, in fact, the grace and vocation proper to the Church, her deepest identity. She exists in order to evangelize, that is to say, in order to preach and teach, to be the channel of the gift of grace, to reconcile sinners with God, and to perpetuate Christ’s sacrifice in the Mass, which is the memorial of his death and glorious resurrection.”

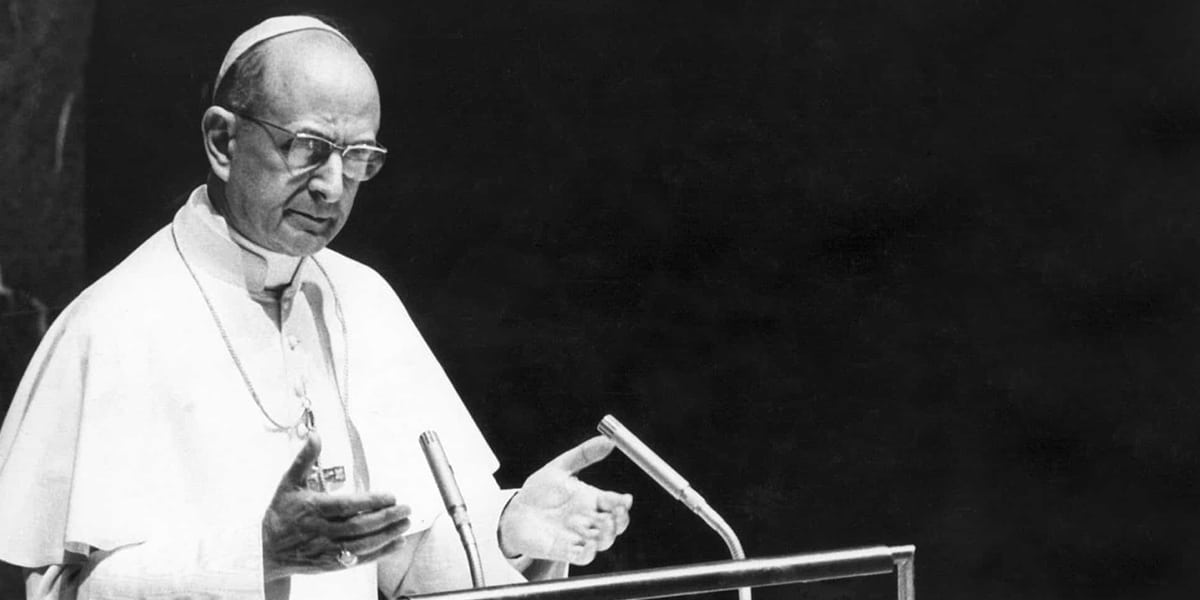

Accordingly, he became, like his namesake, something new in the history of the papacy: a globe-trotting evangelist. He visited six continents. He was a kind of prototype for the great popes who have followed him, leaving the Vatican to bear witness to the flock around the world and to call into the fold those not yet baptized.

This drove his reform of the liturgy as well. Vatican II’s “Sacrosanctum Concilium” (“Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy”) had declared that “all the faithful should be led to that fully conscious, and active, participation in liturgical celebrations, which is demanded by the very nature of the liturgy” (14). The Ordinary Form promulgated by Paul VI sought that, and the goal was in large measure achieved. The implementation of the Extraordinary Form in 2007, while a clear conciliatory gesture to those who prefer Latin over the vernacular, was not a rebuke of Paul’s reform of the Mass. The most obvious evidence of that fact is that the Ordinary Form remains the Ordinary Form.

Defender of the Poor

Pope Paul VI was, in many ways, “to the manor born.” His mother was from a noble family. His father had been a member of Parliament, his brothers a doctor and lawyer. This was reflected in his own career: He never pastored a parish and was funneled straight into curial work. He served three popes before he became pope himself and was accustomed to moving at the very highest levels of the Church.

He was, however, also a committed disciple of Jesus Christ who understood that the Church was called to model Jesus’ teaching to “let the greatest among you be as the youngest, and the leader as the servant” (Lk 22:26). In a dramatic gesture of renunciation, during the Second Vatican Council, he descended the steps of the papal throne, ascended to the altar, and laid the papal tiara on it. Later, the tiara was sold and the money was given to charity. No pope since has worn one.

Pope Paul understood the threats and opportunities confronting the least of these in a world where economic extremes were growing, but economic opportunity was growing as well. His great encyclical “Populorum Progressio” (“The Progress of Peoples”) addressed this, proposing a holistic view of the human person who, to be sure, does not live by bread alone, yet whose physical needs could not be ignored either. He called for complete solidarity with the least of these and a view of material goods as entrusted to the rich for the sake of the poor.

This would enable the poor to sufficient means not only to live, but also to participate in the kingdom of God. His goal in this was spiritual, not political, social, or materialistic.

As he said: “Founded to build the kingdom of heaven on earth rather than to acquire temporal power, the Church openly avows that the two powers—Church and State—are distinct from one another; that each is supreme in its own sphere of competency. But since the Church does dwell among men, she has the duty ‘of scrutinizing the signs of the times and of interpreting them in the light of the Gospel.’ Sharing the noblest aspirations of men and suffering when she sees these aspirations not satisfied, she wishes to help them attain their full realization.”

Defender of Liberty

Pope Paul VI understood one of the great developments of doctrine that the Church slowly came to grasp: Though “error has no rights,” nonetheless, persons in error do have rights. It was this development that led to the formulation of the principles enshrined in “Dignitatis Humanae” (“Declaration on Religious Liberty”).

Faced with a world where a third of the population were bound under the yoke of Communism, the Church profoundly stated the Christian doctrines of freedom of conscience and the necessity for Catholics to uphold liberty for all—not merely for Catholics.

Paul VI put legs on this by undertaking dialogue with a host of people and insisting that such dialogue be predicated on the equal dignity of all participants. This did not mean that he sacrificed the reality that the fullness of truth subsists in the Church, which is the body of Christ. Nor did he see dialogue as an end in itself. Rather, he had the confidence of St. Thomas Aquinas that any movement by anybody toward the truth was movement toward Jesus Christ.

For this reason, he did not fear religious liberty since, with St. Paul, he knew that “where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom” (2 Cor 3:17).

Defender of Life

At the same time, Paul VI understood the distinction between liberty and license. The misuse of freedom leads, as he saw, not to greater freedom, but to slavery, the consequence of sin. The most famous and countercultural expression of this Christian conviction was his restatement of traditional Catholic sexual ethics in “Humanae Vitae,” which insisted that the sexual act was intended only for marriage between one man and one woman, that our sexual nature was made by God to bring forth children, that thwarting that nature by artificial contraception was destructive and warping to our understanding of human sexuality, and that the embrace of a contraceptive culture would inevitably lead to the devaluation of human life and human relationships, as well as the rise of an abortion culture.

Suffering Saint

Pope Paul’s life in the center of the maelstrom of change in the ’60s and ’70s made him a lightning rod for hostility, which he bore with heroic courage. In his piety, he was every inch an ordinary Catholic. He had a strong devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary, naming her Mother of the Church and asking for her intercession for the council.

Paul VI suffered much in his lifetime. He witnessed the agonies of two world wars. He loved and admired Pope Pius XII, and it hurt him to see that pope accused of failing in his duty during the Holocaust. He suffered as well from accusations of heterodoxy after the council and from the fury heaped on his head for “Humanae Vitae.” Unlike many of his predecessors, he did not excommunicate opponents and bore much opprobrium from enemies—as well as from those who thought him weak for not punishing those enemies.

In addition to the controversy, near the end of his life, his friend Aldo Moro, the former prime minister of Italy, was kidnapped by terrorists and held hostage for 55 days. Pope Paul begged for his life and even offered to exchange places with him, to no avail. Moro was shot to death and his body left in the trunk of a car. Pope Paul, heartbroken, celebrated his state funeral Mass.

As the summer of 1978 wore on, his health failed. He died on August 6, 1978. His burial was characteristically humble in obedience to his will that stipulated he be placed in the “true earth” with no ornate sarcophagus.

One of his last writings sums up well his life of patient Christian suffering: “What is my state of mind? Am I Hamlet? Or Don Quixote? On the left? On the right? I do not think I have been properly understood. I am filled with ‘great joy.’ With all our affliction, I am overjoyed (2 Cor 2:4).”

1 thought on “St. Paul VI: Bridge Builder”

Beautiful, such depth brilliantly summarised!. Have to read through again, as there is so much to appreciate & absorb. Dear Saint

you were always loved in our home, during/after your time on earth.

Now, all HOME with JESUS, except me. Dear Saint Pope Paul VI, please pray for me/us (sisters & brothers) on the lowest rung esp those in my heart. Need a miracle or two! Please help us.