Throughout the last years of his papacy, John Paul II relied on God to endure his failing health.

It is no secret that Karol Wojtyla, as a young man and even during the early years of his pontificate, was a picture of health, vigor, and vitality. As an athlete skilled in soccer, swimming, canoeing and skiing, he exhibited a great physical presence.

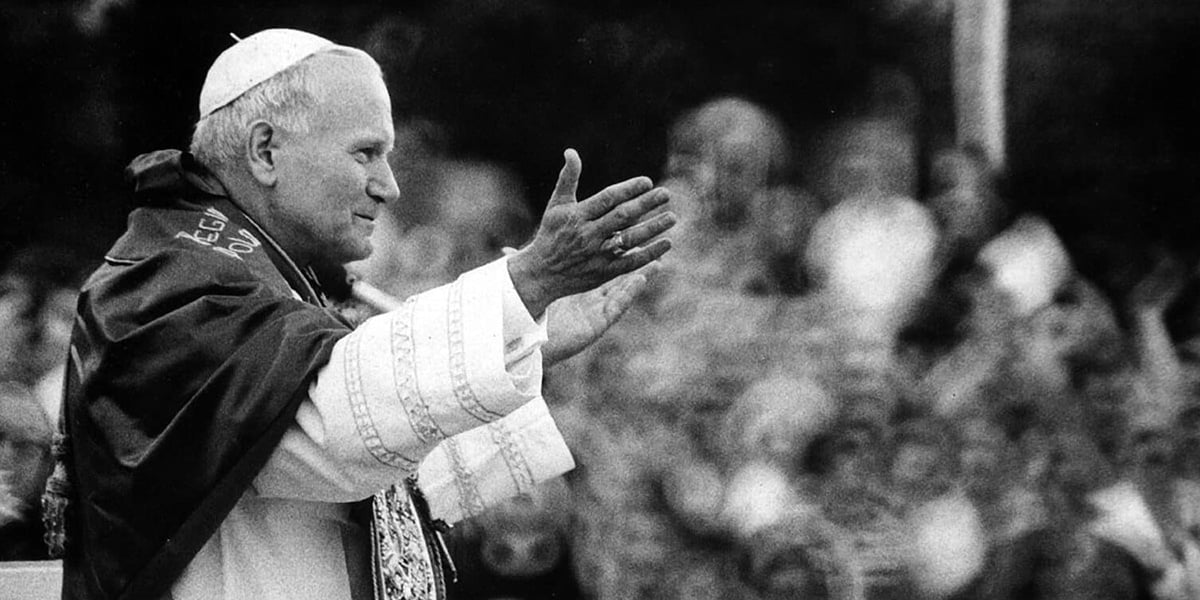

During his papal trip to the United States in 1979, he rode through Manhattan in the back of a limousine with an opening in the roof that allowed him to be visible to the crowd from the waist up. He was in excellent physical condition, waving to the crowds with just the right amount of drama as the vehicle moved slowly along. (This was before the 1981 assassination attempt in Rome and the days of the “popemobile,” with its bulletproof glass protecting the pope.)

These are all reminders of John Paul’s healthier days when he had all the physical stamina and charm any human could want. The pope did regain—for a time—his health and vigor after recuperating from the 1981 assassination attempt.

In the early 90s, however, a series of health problems began to take their toll. In 1992, the pope had colon surgery, involving removal of a noncancerous tumor. The next year he fell and dislocated a shoulder. In 1994, he suffered a broken femur in another fall. An appendectomy followed in 1996. During these years, moreover, a Parkinson-like condition, if not the disease itself, began to reveal its visible effects.

The point of these sobering details is to show that John Paul was clearly entering the part of his life’s journey marked by failing health and suffering.

Describing the Holy Father in the fall of 1998, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger stated: “The pain is written on his face. His figure is bent, and he needs to support himself on his pastoral staff. He leans on the cross, on the crucifix….” Certainly John Paul II was beginning to lean on Christ’s cross in more ways than one.

Bearing Infirmities with Honor

The January 1998 papal trip to Cuba posed a sharp contrast to John Paul’s United States visit in 1979. As a writer for St. Anthony Messenger, who had personally covered both his 1979 USA trip and the Cuba trip of ’98, I had a firsthand experience of the enormous change in the pope’s health. In Cuba the pope’s athletic stamina was gone. His gait was slow and at times shuffling, his speech was often slurred and his hand sometimes trembled.

But frankly, I felt there was something beautiful and noble in the pope’s witness. His courageous perseverance in carrying out his activities as pope, despite his physical afflictions, was a heart-lifting example for all of us. This was, perhaps, doubly true for all those people around the globe who were themselves bearing some cross or affliction. Many of us, faced with the same tests, would be tempted to shrink from public view, as if infirmity were an embarrassment or personal disgrace.

Not so our brother John Paul II! He refused to go into hiding as long as he could effectively fulfill his ministry as pope. He bore his infirmities as if they were badges of honor and opportunities for imitating the courage of the suffering Christ.

His humble, unpretentious and unembarrassed acceptance of suffering was a dramatic form of witness. The pope offered the world a wonderful model for responding with grace to the test of suffering and illness. As Cardinal Ratzinger observed, John Paul II helps us realize that “even age has a message, and suffering a dignity and a salvific force.”

While the pope was in Cuba, this anecdote was circulating. Someone asked the pope if it would be better if he retired. “After all, Holy Father,” the questioner pointed out, “you have trouble walking and your hand trembles.”

“Fortunately,” the pope quipped, “I don’t run the Church with my feet or my hands, but with my mind!”

We cannot be certain of the authenticity of the story, but it captures something of the pope’s spirit—and his ability to respond to challenges with good humor.

Writing about the Meaning of Suffering

Besides being a heroic witness in the face of suffering, Pope John Paul II has often written inspiringly on the subject. In 1984, for example, he published the apostolic letter “On the Christian Meaning of Suffering.” When confronted with suffering, most of us desperately seek answers to the question Why? Why me? Why now? Why in this unexpected form?

The pope, in his letter, states that Christ does not really give us an answer to such questions, but rather a lived example. When we approach Christ with our questions about the reason for suffering, says the pope, we cannot help noticing that the one to whom we put the questions “is himself suffering and wishes to answer…from the Cross, from the heart of his own suffering….

“Christ does not explain in the abstract the reasons for suffering,” he points out, “but before all else he says: ‘Follow me!’ Come! Take part through your suffering in this work of saving the world…. Gradually, as the individual takes up his cross, spiritually uniting himself to the Cross of Christ, the salvific meaning of suffering is revealed before him” (26).

In 1993, Pope John Paul II instituted the Annual World Day of the Sick as a way to bring compassion and greater attention to the sufferings of humanity, as well as to the mystery of suffering itself. The event is held on February 11 each year on the feast of Our Lady of Lourdes. The pope explains that the Lourdes “shrine at the foot of the Pyrenees has become a temple of human suffering” (6).

In John Paul’s message for that First Annual World Day of the Sick, he offered these words of comfort to suffering people around the world: “Your sufferings, accepted and borne with unshakeable faith, when joined to those of Christ take on extraordinary value for the life of the Church and the good of humanity” (5).

He also suggested in the same message that suffering can be transformed into something noble and good: “In the light of Christ’s death and resurrection, illness no longer appears as an exclusively negative event,” he said. “[R]ather, it is seen as…an opportunity ‘to release love…, to transform the whole of human civilization into a civilization of love’ (Apostolic Letter Salvifici doloris, 30)” (3).

We cannot really choose to have no pain in our lives, because pain in some form is inescapable. We have no choice about pain or suffering. Sooner or later everyone must face it. Even Jesus and his mother had to undergo pain.

Whether we bear it with love or not, however, is a different matter. We do have a real choice there. We are free to choose “the pain of loving” or “the pain of not loving,” the latter being a pain that is empty and barren—a pain without any redeeming qualities. We know that Jesus and his mother and other heroic witnesses like John Paul have chosen the “pain of loving.” That is, they undergo suffering for the love of God and of humanity, so their pain has rich meaning.

The Pope’s ‘Letter to the Elderly’

In 1999, Pope John Paul II published a “Letter to the Elderly.” Just as earlier in his pontificate the pope often showed a special concern to the youth of the world, so now he shows a similar concern for elderly people, who also represent a very important segment of humanity. Like the pope himself, a good number of elderly people are susceptible to suffering and failing health.

In his comments to the elderly, the pope reveals some of his own sentiments about the challenges associated with aging, failing health and the end of life on earth. He encourages his elderly brothers and sisters “to live with serenity” the years that the Lord has granted to them.

Then, John Paul adds this poignant, personal note: “…I feel a spontaneous desire to share fully with you my own feelings at this point of my life, after more than 20 years of ministry on the throne of Peter….Despite the limitations brought on by age, I continue to enjoy life. For this I thank the Lord. It is wonderful to be able to give oneself to the very end for the sake of the Kingdom of God!

“At the same time, I find great peace in thinking of the time when the Lord will call me: from life to life! And so I often find myself saying, with no trace of melancholy, a prayer recited by priests after the celebration of the Eucharist: In hora mortis meae voca me, et iube me venire ad te—at the hour of my death, call me and bid me come to you. This is a prayer of Christian hope, which in no way detracts from the joy of the present, while entrusting the future to God’s gracious and loving care.

A Prayer for Peace at Life’s End

John Paul concludes his “Letter to the Elderly” with a prayer that expresses well his own faith-filled response to the mystery and test of suffering:

“Grant, O Lord of Life, that we may… savor every season of our lives as a gift filled with promise for the future. Grant that we may lovingly accept your will, and place ourselves each day in your merciful hands. And, when the moment of our definitive ‘passage’ comes, grant that we may face it with serenity, without regret for what we shall leave behind. For in meeting you, after having sought you for so long, we shall find once more every authentic good which we have known here on earth, in the company of all who have gone before us marked with the sign of faith and hope. Mary, Mother of pilgrim humanity, pray for us ‘now and at the hour of our death.’ Keep us ever close to Jesus, your beloved Son and our brother, the Lord of life and glory. Amen” (18).

6 thoughts on “Notes from a Friar: Pope John Paul II and Suffering”

Simply beautiful. Words to live by each and every day. My hope is to thread these thoughts into my life in thanksgiving for my gifts and my sufferings – both physical and emotional. Thank you.

Pingback: How to Die Like Tim Keller – ChristianHeadlines.com | Christian Chat - Christians Chat Network News

Saint John Paul II Pray For Us

This Pope broke rocks in a quarry for Germans and had holes in his shoes. If they gave him a break he was on his knees praying. Going from this to the Vicar of Christ is not ordinary by any means but totally spiritual!

Thanks be to GOD for all our wonderful clergy

I’m a caregiver for my HWP. I wanted to inform PWP that there’s hope, the binehealthcenter . c om has been of great help. the PD-5 treatment programme they offer has completely help with reversing my husband Parkinson’s symptoms.