He traveled from Oklahoma to Guatemala to serve the poor and ended up giving his life in the name of peace and justice. His legacy continues to inspire those who want to live out the Gospel as he did.

On July 28, 1981, at 1:30 in the morning, three Spanish-speaking Ladino (nonindigenous) men snuck into the rectory of Santiago Apóstol Church in Santiago Atitlán, Guatemala, looking for the parish priest. They found and seized Francisco Bocel, the 19-year-old brother of the associate pastor, put a gun to the terrified young man’s head, and threatened to kill him if he did not take them to the pastor.

Bocel led the attackers down the stairs and to the door of a corner utility room. He knocked, calling out in terror, “Padre, they’ve come for you.” That’s when Father Stanley Rother, aware of the danger to the young man, opened the door and let his killers in.

The assailants wanted to kidnap Father Stanley, turn him into one of the desaparecidos (the missing). But he would have none of that. He was aware of Bocel, of the nine unsuspecting sisters in the convent across the patio, and of the other innocents in the rectory that night—all in danger of also being dragged away.

And Father Stanley knew they would torture and, ultimately, kill him. The priest—affectionately called “Padre Francisco” because of his middle name, Francis—never called for help. From his hiding place, Bocel heard the muffled noises of a struggle—bodies crashing into furniture and each other, several thuds. There was a gunshot. Then another. Then silence, followed by the sound of scrambling feet running away.

He rushed to wake up Bertha Sanchez, a nurse volunteer staying in the parish complex, alerting the Carmelite sisters across the courtyard from the rectory: “They killed him! They killed Padre Francisco!”

The women ran in and found Father Stanley shot in the head and lying in a pool of his blood. They immediately began to pray. His dear friend Bertha pronounced Father Stanley Francis Rother dead at the scene. No one has ever been prosecuted for his killing.

40 Years Later

This July 28 marks the 40th anniversary of Blessed Stanley Rother’s martyrdom, although due to the pandemic, it will be a much more subdued celebration than that of previous years. In Santiago Atitl√°n, and la Iglesia Parroquial de Santiago Ap√≥stol, which gives the town its name, the people remember and honor a faithful priest, a shepherd who proclaimed the Gospel with his life, a courageous man who chose to remain with them even when violence threatened—and eventually took—his life.

In a very real way, “Padre Apla’s”—as his Tz’utujil Mayan parishioners named him in their native language—remains their priest. And they come to him daily, asking for his help and intercession—much as they did during the 13 years that he served them. His death, like his life, is one more outward sign of his deep and abiding holy love for them.

“El beato [The blessed] is our example in how he chose to remain with the needy and marginalized, especially during a time of violence,” emphasizes 42-year-old Felipe Coché, a native of Santiago Atitlán. “Now more than ever, the same people that Padre Apla’s served in his time here are in need, especially in the fincas [rural areas] and remote areas outside Santiago. For me, el beato and his courage are my model for serving those in need,” adds Coché, speaking in Spanish, his second language after Tz’utujil.

For Coch é, whose father was a close friend of Blessed Stanley and accompanied the priest on visits to the sick, the American martyr remains close to his heart, especially his love in service of neighbor and his bravery at a time of persecution. “We remember him for defending and proclaiming the good news of the Gospel, and how he did not abandon his people, even to his death.”

The town and parishioners are delighted to be able to celebrate and remember the 40th anniversary of Blessed Apla’s’ martyrdom, says Coché.

Although COVID-19 restrictions still forbid public processions or large town celebrations, “the people will venerate him in home devotions and a visit to the church,” explains the father of two girls. On July 28, the day of his death, the parish plans to celebrate an open-air Mass on the plaza in front of the church.

The Oklahoma Missionary

Born on March 27, 1935, in a farmhouse in the middle of an Oklahoma dust storm during the Great Depression, Stanley Francis Rother was listed in his high school yearbook at Holy Trinity Catholic School as president of the Future Farmers of America.

But the farm boy from Okarche decided to plant a different kind of harvest. After graduating from high school, Stanley crossed the Red River for San Antonio and the seminary. Yet the path to the priesthood would be more difficult than Stanley anticipated.

He struggled in his studies—especially with learning Latin, which led him to fail his first year of theology. When the seminary sent him home, suggesting that he consider a different vocation, Stanley requested another chance from his bishop, who agreed to look for a new venue for him.

When Stanley’s fifth-grade teacher, Sister Clarissa Tenbrink, heard the news that he had flunked out of seminary, she wrote Stanley a letter to encourage him. “He wanted to be a priest so badly. He was very discouraged. So I reminded him of the Curé of Ars,” French priest St. Jean-Baptiste-Marie Vianney, who also struggled with academics and was notably deficient in Latin. “I told Stanley that if he really wanted to be a priest, then he should pray, and trust, and God would take care of things.”

In 1963, Stanley successfully completed his studies at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary in Emmitsburg, Maryland, hometown of the first American saint, Elizabeth Ann Seton. He was ordained a priest for the then Oklahoma City and Tulsa Diocese on May 25, 1963, at age 28. Father Stanley served the first five years of his priestly ministry without much notice in various Oklahoma assignments. But everything changed when he volunteered to serve in Guatemala.

When he arrived in Santiago Atitlán in 1968, Stanley instantly fell in love with the volatile and stunning land of volcanoes and earthquakes, but above all, with its people. He and the other 11 people who made up the Oklahoma mission team established the first farmers’ co-op, opened a school, built the first hospital clinic, and created the first Catholic radio station, which was used for catechesis.

More importantly, when the first Oklahoma missionaries arrived at the 400-year-old parish, there had not been a resident priest for over a century at the oldest parish in the diocese. The people were as malnourished spiritually as they were physically. While he did not institute the project, Father Stanley was a critical driving force in establishing Tz’utujil as a written language, which led to the New Testament in Tz’utujil being published after his death.

In a manner both humorous and courageous, the seminarian who struggled with learning Latin became the missionary priest who not only learned Spanish, but also became completely fluent in the rare and challenging Tz’utujil language of his 25,000 Tz’utujil Mayan parishioners.

“This language is fantastic,” Father Stanley wrote in a letter to his sister. “It isn’t related to any other here in Guatemala. There are 22 different Indian languages here.” About the extra effort required, he added, “[I]t will be worth every minute when I can go out and be able to speak with all the people and not just the 20 to 30 percent who know Spanish.”

And the farmer from Okarche, who loved the land and recognized God in all of creation, was never afraid to get his own hands dirty working the land side by side with the people—a trait deeply loved by his parishioners.

When Guatemala’s violent civil war made its way to the remote village in the late 1970s, Father Stanley’s response was to show his people the way of love and peace with his life. He walked the roads looking for the bodies of the dead to bring them home for a proper burial, and he fed the widows and orphans of those killed or parishioners who had gone missing.

“And what do we do about all this?” wrote Father Stanley to a friend in 1980.” What can we do, but do our work, keep our heads down, preach the Gospel of love and nonviolence.”

To use Pope Francis’ image, Father Stanley was a shepherd who smelled like his sheep.

‘The Shepherd Cannot Run’

In a letter dated September 1980 to the bishops of Tulsa and Oklahoma City, Father Stanley described the political and anti-Church climate in Guatemala:

“The reality is that we are in danger. But we don’t know when or what form the government will use to further repress the Church. . . . Given the situation, I am not ready to leave here just yet. There is a chance that the government will back off. If I get a direct threat or am told to leave, then I will go. But if it is my destiny that I should give my life here, then so be it. . . . I don’t want to desert these people. There is still a lot of good that can be done under the circumstances.”

Yet a few months later—and six months before his murder—Father Stanley and his associate pastor left Guatemala under threat of death after witnessing the abduction of a parish catechist. He returned, however, to his beloved Guatemala in time to celebrate Holy Week in April of 1981, ignoring the pleas of those who urged him to consider his own safety.

“He knew the dangers that existed here at that time and was greatly concerned about the safety and security of the people,” recalled Archbishop Emeritus Eusebius J. Beltran, in a 30th-anniversary message to the community of Cerro de Oro, one of the mission’s satellite churches near Santiago Atitlán. “Despite these threats and danger, he returned and resumed his great priestly ministry to you. . . . It is very clear that Padre Apla’s died for you and for the faith,” emphasized Archbishop Beltran, who served as bishop of Tulsa in 1981 when Father Stanley was murdered.

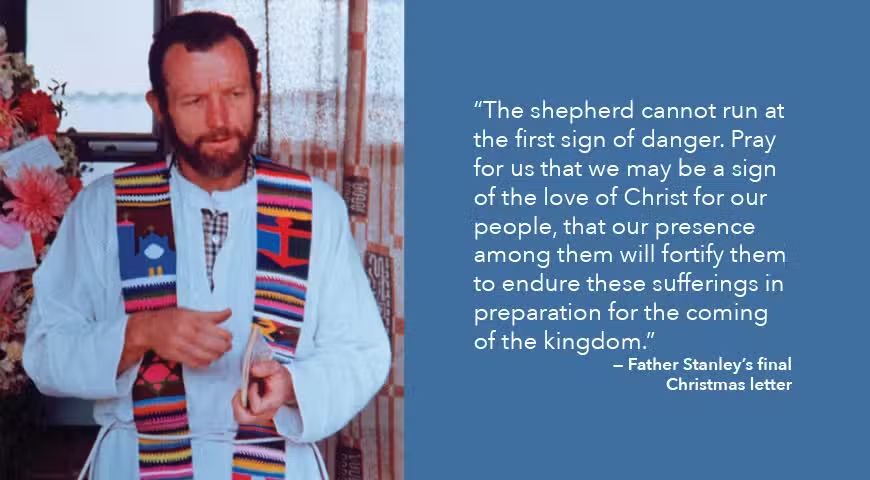

In his final Christmas letter from the mission to the Church in Oklahoma in 1980, Father Stanley concluded: “The shepherd cannot run at the first sign of danger. Pray for us that we may be a sign of the love of Christ for our people, that our presence among them will fortify them to endure these sufferings in preparation for the coming of the kingdom.”

America’s Ordinary Martyr

By constantly striving to be present to the people in front of him, to the needs in front of him, Blessed Stanley Rother proclaimed a God who lives and suffers with his people. In the end, the choice to die for the Tz’utujil people was a natural extension of the daily choice he made to live for them and in communion with them. His death was nothing less than a proclamation of God’s love for the poor of Santiago Atitlán.

Yet in a very real way, Blessed Stanley lived an ordinary life. He chose to make it a life of ordinary heroic virtue, with confident trust in Divine Providence and a keen awareness of God’s presence in the small and insignificant quotidian moments of parish life, as well as in the unfamiliar and often unexpected events of missionary life.

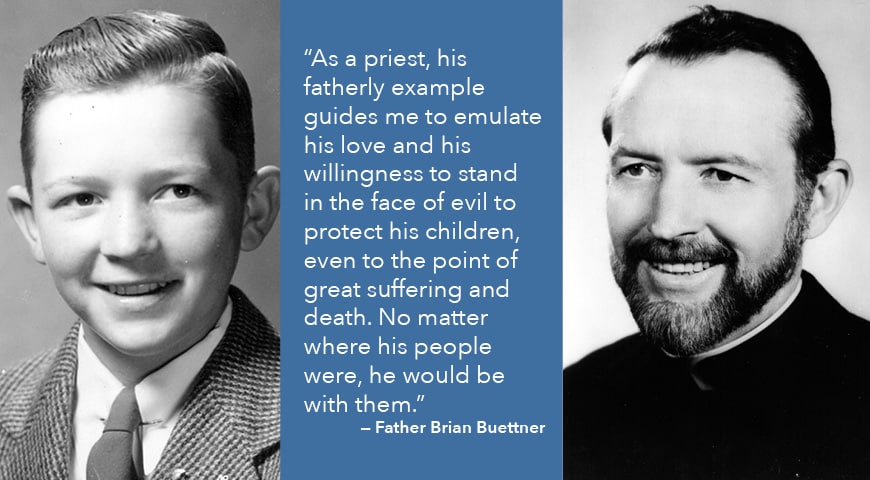

“While we focus a lot on his heroic example through his martyrdom, my heart always returns to his example of fatherhood. By following the Lord’s supernatural call, this ordinary man drew many people to Christ,” declares Father Brian Buettner, 38-year-old pastor of St. Joseph’s Old Cathedral in Oklahoma City. “As a priest, his fatherly example guides me to emulate his love and his willingness to stand in the face of evil to protect his children, even to the point of great suffering and death,” he says. “No matter where his people were, he would be with them.”

Even though the specifics of his life are much different than her own life, for high school teacher and Bronx native Valerie Torres, Blessed Stanley Rother is both relevant and inspiring. “The fact that he worked to have the New Testament translated to the language of the Guatemalan community so that his community could read and pray with the Scripture in their own language truly touches my students,” explains Torres, who includes Father Stanley every year in her high school curriculum at Aquinas High School in the Bronx.

“In my community, the students and local youth often serve as translators for their parents or grandparents. So many of our youth see their parents struggle to learn English, struggle to learn to read,” making his attentiveness to language very meaningful.

It is Blessed Stanley Rother’s love, courage, perseverance, and presence that make him the American saint we need, emphasizes Torres. “He embraced the preferential option for the poor and vulnerable. He witnessed Jesus each day of his life!

“We need US witnesses. We need witnesses who reflect our communities. We need contemporary witnesses,” she adds. Blessed Stanley reminds “our youth and their families—[and] all of us striving to live holy lives—that we are on the path to sainthood, even as we strive to dream and fulfill our God-given mission.”

According to Father Lynx Soliman, a newly ordained priest for the Diocese of Newark, Blessed Stanley Rother is the saint needed for the Church in America “precisely because he had the heart of a missionary,” and all of us are called to be missionary disciples. “As the first American martyr, I’m excited to see how many seeds will sprout from his blood for the glory of God and the good of souls,” Father Soliman says.

“And the universal Church will benefit from [declaring] such a saint because of how ordinary Blessed Stanley was,” notes Father Soliman, “and yet how attractive was his ‘ordinariness’! The world needs a man like Blessed Stanley to be declared a saint so that the mission of the Church will continue to thrive in a world that often tries to suffocate it.”

For Shellie Greiner, it is both his faithfulness and his modern-day story that make Blessed Stanley Rother attractive. “We have come to know him as ordinary, but [also] extraordinary,” explains the Oklahoma native.

“And I am ordinary, [so] can I become extraordinary through his example of simple living, of giving himself completely? Would I have the boldness to stand up for the Catholic faith and be willing to die for it today? I hope I don’t have to, but please, Lord, let me be bold always like Stanley Rother!”

A Beacon of Faith and Discipleship

The Blessed Stanley Rother Shrine will open in 2022, a stone’s throw from I-35, the major north-south highway crossing the middle of the United States from Minnesota to the Mexico border.

The 2,000-seat church, designed in the Spanish mission style echoing Blessed Stanley Rother’s church in Santiago Atitlán, will include a chapel where his body will be entombed. “I hope this shrine will be a beacon on I-35 drawing many to come and find out more about Blessed Stanley, to open their eyes and hearts to the power of faith in our Lord,” says Molly Bernard, chair of the Rother Shrine Building Committee.

“I have come to appreciate Blessed Stanley’s humility and service. He is a role model for us when we face tough situations,” notes Bernard, “and I pray to him daily to intercede for us in our archdiocese. He is truly a hero.”

“I hope that having this shrine in the heart of Oklahoma and in the heart of our archdiocese will teach all of us about pilgrimage as a model for a life of discipleship and mission,” emphasizes Oklahoma City Archbishop Paul S. Coakley. “I hope it will be a center for evangelization and formation that will nurture the faith of all who come.”

1 thought on “Blessed Stanley Rother: Martyr, Missionary, Shepherd”

I am from Tulsa and reading about his story makes me happy someone from a small town is now canonized and publicly known for his faith.