Pope Francis says Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is a role model for Americans. A scholar of Black Catholic history explains why.

When Pope Francis arrived at Joint Base Andrews on September 22, 2015, the families of President Barack Obama and Vice President Joseph Biden led his greeting party. The Obama family’s presence in the party demonstrated how much the United States had changed since Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. led a voting-rights march from Selma to Montgomery 50 years earlier. In 1965, when wide swaths of African Americans were excluded from voting, the idea of an African American president was hardly dreamed of by the average American, Black or White.

Similarly, one of the central events of Pope Francis’ visit, an address to the US Congress, would also have been unheard-of in 1965. When Senator John F. Kennedy ran for president in 1960, he was compelled to assure the American public that if it placed its trust in him, he would not take his marching orders for governing from the pope.

Although he was elected president, Kennedy’s religion continued to be suspect by many Americans. Not until the 1980s did the United States establish formal diplomatic ties with the Holy See. And, though the first papal visit to the United States took place in the fall of 1965 with Pope Paul VI’s address to the United Nations, and many other papal visits have happened since, Pope Francis’ invitation to address Congress signified a major shift in American thought about how the United States should relate politically to the Holy See.

Perfect Timing

Whether or not the average American was aware of the historic significance of Pope Francis’ visit, most were simply happy to have him here. His visit came at the end of a summer that had its share of national sadness, anger, and bewilderment. The Black Lives Matter movement helped bring to national attention the killing of unarmed Black men and women around the United States at the hands of police officers. Various state legislatures were working to undo safeguards designed to keep together families that included undocumented immigrant parents and to protect the future of “Dreamers,” undocumented youth who were raised in the United States. Mass shootings soared that summer with the racially motivated massacre in Mother Emmanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, and the movie theater shooting in Lafayette, Louisiana.

Poverty continued to dog many Americans. And political polarization intensified as Democrats and Republicans launched bids to become their party’s nominee for president in 2016.

Pope Francis’ visit could not have come at a better time. For about a week, his presence, his interest in us, his attention to our problems, and his ability to personify the theme of his visit, “Love is our mission,” seemed to lift the spirits of Americans. During his many public and private events, Pope Francis reached out to us, reminded us that we are made in God’s image and likeness, and called us to remember times in our history when we transcended self-interest, hatred, and fear. It is no wonder the Monday after the pope departed from the United States, NBC weatherman Al Roker expressed what many of us felt: “I miss the pope.”

Welcome to ‘Our Common Home’

The morning after his arrival, President Obama formally welcomed Pope Francis to the United States on the lawn of the White House. During the Civil War, a group of Black Catholic Washingtonians held a fund-raiser on this same lawn to build the first Catholic church in the nation’s capital for African Americans, St. Augustine’s Catholic Church. In his remarks on the lawn, Pope Francis spoke of the importance of protecting and defending “our common home” for our children and future generations around the globe.

He admonished us to act on our responsibility to care for creation and our neighbors, saying, “To use a telling phrase of the Reverend Martin Luther King, we can say that we defaulted on a promissory note, and now is the time to honor it.”

At the conclusion of the welcoming ceremony, St. Augustine’s Gospel Choir, the choir of that same historic church, sang for Pope Francis. For a group in the Catholic Church that is often overlooked when people think, speak, or write about American Catholics, the setting, the singers, and the song were an affirmation of the place of Black Catholics in the Church in the United States.

In the days leading up to the visit, many media sources wondered how he would relate to issues of particular concern to African Americans. In particular, several articles speculated about whether Pope Francis would directly address ways that racism and its effects were still of consequence in America. Archbishop Joseph E. Kurtz of Louisville, president of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, also expressed hope that the pope would address racism.

In the summer of 2015, a small delegation from the Black Lives Matter movement accepted an invitation to meet with papal advisors in Vatican City. Pope Francis’ advisors wanted to learn more about the racial problems and situations in the United States that led to the creation of the movement.

Black Lives Matter leaders informed the pope’s advisors about the various ways the lives of Black people are devalued in American society and the purpose of their movement, which calls for investigations of the public shootings of Black people, particularly those committed by police officers; the demilitarization of local police forces; and accountability for police violence in communities of color. Their hope in having these meetings was that Pope Francis would address America’s troubled racial relations.

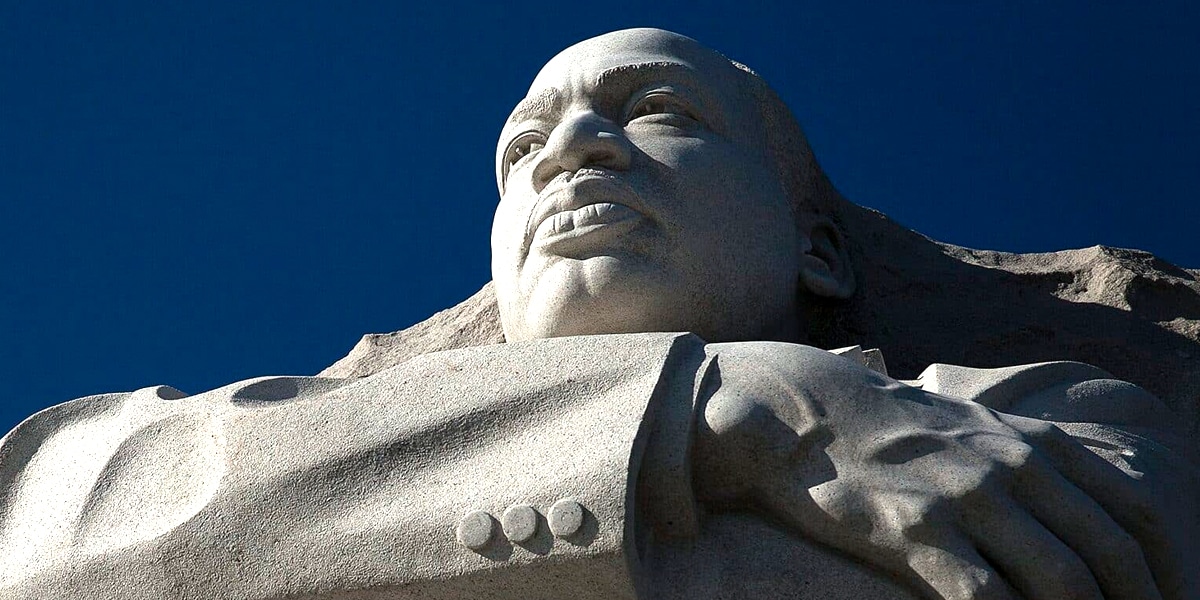

At the outset of his remarks to Congress, Pope Francis declared his intention to “dialogue” with us through “the historical memory of your people.” The people Pope Francis had in mind were Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., Dorothy Day, and Thomas Merton. In the pope’s view, they tried “by hard work and self-sacrifice—some at the cost of their lives—to build a better future.” Pope Francis directed our attention to them because they provide models and methods that we can apply to our current problems.

Model of Justice and Freedom

To dialogue with our “people,” Pope Francis could not have made a better choice than Dr. King. It is difficult to imagine an American born after 1930 or educated anywhere in the United States after 1986, the year that Dr. King’s birthday became a national holiday, who does not have at least a rudimentary understanding of his meaning to America. Dr. King is the American icon of freedom and justice. He is the single best American teacher of the power of love over hate. We hear his voice whenever any schoolchild steps up to recite from the “I Have a Dream” speech. We are beneficiaries of the revolution he led to make the United States more just and compassionate. Calling on Americans to be people of justice and compassion was very much on the mind of Pope Francis as he addressed Congress last fall.

Readers of the text of Pope Francis’ address to Congress will be struck by how little he actually said about Dr. King. He recognized the role Dr. King played in the Selma campaign and the 50th anniversary of the march from Selma to Montgomery for voting rights. The pope said that Selma was part of King’s “campaign to fulfill his ‘dream’ of full civil and political rights for African Americans.” This is the “dream” Dr. King shared with over 250,000 people on the occasion of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August 1963.

Pope Francis then focused his remarks on the situation of immigrants and their treatment in the United States today. He said he was glad to know that America was still a “a land of dreams. Dreams which lead to action, to participation, to commitment. Dreams which awaken what is deepest and truest in the life of a people.” He also called attention to the plight of immigrants and refugees and called on the people of the United States to remember their own immigrant roots.

The pope admonished us that when “the stranger in our midst appeals to us, we must not repeat the sins and the errors of the past. We must resolve now to live as nobly and as justly as possible, as we educate new generations not to turn their backs on our ‘neighbors’ and everything around us. Building a nation calls us to recognize that we must constantly relate to others, rejecting a mindset of hostility in order to adopt one of reciprocal subsidiarity, in a constant effort to do our best. I am confident we can do that.”

A Dream Deferred?

What was the connection between Pope Francis’ brief remarks about Dr. King and his more expansive commentary on justice for immigrants and refugees? How does the civil rights movement of the 1960s relate to today’s immigrants? How does Dr. King’s “dream” relate to the “Dreamers” of today? And what about racism and Black Lives Matter?

I believe the answers to these questions lie in the “I Have a Dream” speech. The first thing Dr. King established in this speech is that they were gathered in Washington to demonstrate for freedom. As he stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, he turned to history and recalled the Emancipation Proclamation. He asserted that the promise of freedom that document gave to African Americans a century earlier was not yet a reality for them. King spoke of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence as a promissory note for “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” But, he asserted, “It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned.”

Then King declared that they were in Washington to ask the nation to make good on this promise to all people, regardless of race. Fundamentally, Dr. King was calling for the nation to respect the full citizenship rights of African Americans.

This call resonates today with immigrants, documented and undocumented alike, who have come here seeking to make better lives for themselves and their families and who contribute to the good and prosperity of America in untold ways. It also reflects the situation of many American communities of color who still do not always experience the respect and privileges they are due as citizens. Dr. King warned that these rights must be respected. If not, he said, “there will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro [African American] is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright days of justice emerge.”

Next, Dr. King spoke of the “marvelous militancy” which is the work of African Americans and their allies who stand up for justice and civil rights. Today we have a “marvelous militancy” in the young “Dreamers,” who are organized with allies to work for their full citizenship and for reforms in our immigration laws and practices. We also have this “marvelous militancy” in the Black Lives Matter movement that draws much of its inspiration from the civil rights movement that Dr. King led. As Dr. King asserted, the “marvelous militancy” then and now benefits from “many of our white brothers [and sisters]” who “have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny.”

Finally, in the “I Have a Dream” speech, Dr. King emphasized that we are all made in God’s image and likeness and that we are all children of God. These concepts are deeply resonant with the concept of dignity in Catholic social teaching. Our dignity is the foundation for our right to justice. But the truth is that we are not living in a society that respects these principles. The persistence of racism and ugly anti-immigrant rhetoric and actions are damning evidence of our failure to see God in our brothers and sisters. This troubled Dr. King, and it clearly troubles Pope Francis, too. That’s why I think Pope Francis wanted to make us remember Dr. King and his “dream” while he was here in the United States.

Sisters and Brothers in Christ

Dr. King’s basic message was that we need each other. When one of us suffers, we all suffer. I am not free until we are all free. Our need to understand ourselves as deeply related to our sisters and brothers is what Catholic social teaching means by solidarity. Solidarity was central to everything Dr. King said and did, and it is what Pope Francis embodies and advances consistently today.

Dr. King’s “dream” is rooted in our rights as sons and daughters of God. Among these are our rights to be judged by our characters and not by our skin colors, to be in each other’s company as equals, to experience justice and freedom, and to see “the jangling discord of our nation” transformed into “a beautiful symphony of brotherhood [and sisterhood].” I believe Pope Francis chose Dr. King because he wants us to wake up and remember that the “dream” is for us to become a real community rooted in love and respect for one another.