Jesus respected the diverse backgrounds of his listeners. Today the Catholic Church is embracing a much wider range of cultures.

“Go into the whole world and proclaim the Gospel to every creature,” Jesus told his apostles (Mk 16:15). Christianity has been doing that ever since, always with a widening sense of how to bring the Gospel to people of different cultures—all created and loved by a God who wishes to share divine life with us.

Unfortunately, Catholic and other Christian missionaries have sometimes been more influenced by their cultural assumptions than by the Gospel they have been commissioned to preach—to evangelize first and then perhaps “civilize.” They have failed to appreciate how much a new culture could teach them about the Gospel they thought they completely understood.

This month the Catholic Church is celebrating Extraordinary Missionary Month on a theme chosen by Pope Francis: “Baptized and Sent: The Church of Christ on Mission in the World.”

November marks the 100th anniversary of “Maximum Illud ” (“That Momentous Task”), Pope Benedict XV’s apostolic exhortation refocusing the Catholic Church’s missionary evangelization.

Although addressed to the Catholic Church, this document has many implications for all Christian denominations facing similar challenges in helping the Gospel take root in a wide variety of cultures. “Maximum Illud” occurred after World War I and the Treaty of Versailles (June 28, 1919); both events profoundly affected the world in which the good news was to be shared.

In varying degrees, all the mainline Christian denominations are much more a “world Church” now than they were in November 1919. Ecumenical and interfaith relations are also generally more positive than they were in 1919.

Changing Demographics

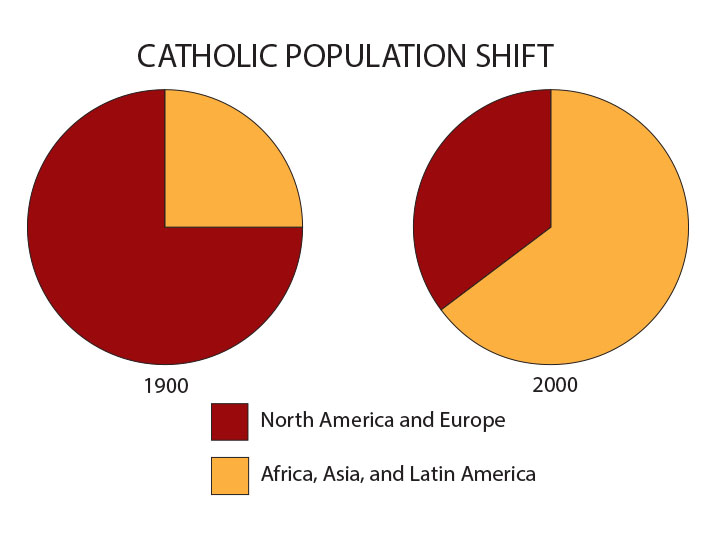

In 1900, only 25 percent of the world’s Catholics lived outside Europe and North America. By 2000, 65.5 percent of the world’s Catholics lived in Africa, Asia, and Latin America (John Allen, The Future Church).

Elsewhere, Allen notes that 392 million of the world’s 459 million Catholics lived in Europe or North America in 1900. A hundred years later, Europe and North America had 12 million fewer Catholics, while 720 million of the world’s 1.1 billion Catholics lived in the global South.

In the 20th century, Africa’s Catholic population has experienced a growth rate of 7,000 percent. More detailed national, regional, and continental statistics are available in Global Catholicism: Portrait of a World Church (Bryan T. Froehle and Mary Gautier, 2003).

Many dioceses were created after 1962. Most of the missionary bishops at Vatican II were from the global North; their successors are almost universally from the global South. The College of Cardinals has experienced changing demographics but far behind those for Catholics worldwide.

Pope Francis is the first pope from Latin America; his predecessors were from Poland and Germany, respectively. The changing face of Catholicism worldwide has become more obvious since 1964 because of extensive papal trips outside Italy and the ability of popes to record video messages in advance of key Church events around the world.

Three Eras of Christianity

In 1979, Karl Rahner, SJ, wrote that Christian history broadly falls into three eras:

1) Jewish-Christian era (AD 30 to AD 70), from the death of Jesus to the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem;

2) European/North American era (AD 70 to AD 1962), when European and North American cultures were the main drivers for missionary evangelization, closely cooperating with colonial powers; and

3) World Church era (1962 to present), for the Catholic Church, at least, a recognition that the Gospel is not spread by reproducing whichever culture brought it to new peoples.

At the end of each era, the Church needed to rethink its cultural assumptions in order to be faithful to its universal mission.

The Church at Vatican II tried to embrace each of the many cultures of its members. Each public session began with a Mass celebrated in one of the Church’s main liturgical traditions, using different vestments, music, and gestures. Some celebrations included dances. Many observers mistakenly considered all this “interesting” but not to be confused with the “real thing” (the Roman rite, soon to be radically revised).

At the start of Era 1, most Christians had been raised Jewish; by AD 70, most Christians were coming from a gentile background. In Era 2, the concern for unity was so strong that many people in the early 1960s thought of the Catholic Church almost as a franchise, whose headquarters is in Rome and whose local bishops act as branch managers lacking any genuine responsibility for the Church beyond their assigned territory. “Synodality” was regarded by many Westerners as a quaint custom very much alive among the Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches.

On October 17, 2015, however, Pope Francis said: “The journey of synodality is the journey that God wants from his Church in the third millennium. A synodal Church is a listening Church, aware that listening is more than hearing. It is a reciprocal listening in which each one has something to learn.” (A synod on evangelizing Amazonia will be held at the Vatican between October 6 and 27, 2019.)

In Era 3, Vatican II’s teaching about collegiality (how the successor of St. Peter and local bishops relate to one another) created a profound sense that any superficial accommodation to local culture would betray Jesus’ command “to proclaim the good news to the whole creation.”

‘Maximum Illud‘ in Context

After Pope Benedict XV noted the good work done by missionaries over the centuries, he identified several urgent needs for Catholic missionary evangelization: involving the entire Church (not simply religious communities of women and men) in missionary evangelization, especially through prayer; reminding missionaries that their first loyalty must be to the Gospel and not to the colonial power from which they came or who provided part of their funding; seriously promoting the setting up of regional seminaries and the training of priests born in the country where they will minister; fostering financial support through missionary organizations; the Society for the Propagation of the Faith (founded in Lyon by Venerable Pauline Jaricot in 1822) was not mentioned by name but was the largest such Catholic organization; recognizing the contribution that women religious make to evangelization through running schools, orphanages, hospitals, and other charitable institutions; reminding everyone, “The Catholic Church is not an intruder in any country; nor is she alien to any people”; denying that those who receive Baptism are abandoning loyalty to their own people “and submitting to the pretensions and domination of a foreign power.”

Pope Pius XI brought six Chinese priests to Rome in 1926 so that he could ordain them as bishops; he also established many more ecclesiastical jurisdictions staffed by newly recruited mission groups. Subsequent popes have stressed how Baptism makes all Catholics missionaries in some way.

By the end of 1945, the United Nations had 51 member states. By the end of 1962, it had 59 more member states, most of them former colonies that became independent countries after World War II. The world in which the Gospel must be preached was changing profoundly.

A Case Study in Inculturation

I offer China’s experience here because the topic of inculturation is key to a book that I coauthored in 1995 with the late Arnulf Camps, OFM: The Friars Minor in China 1294–1955, Especially the years 1925–55. Our work was based on research by Friars Bernward Willeke and Domenico Gandolfi, using information supplied by OFM provinces that by World War II were staffing 28 mission territories in what is now the People’s Republic of China.

Christianity came to China when Alopen, a monk from Syria, arrived in Xian in 635. Influenced by hostile relations with the West, Christianity there practically disappeared two centuries later. The Franciscan John of Monte Corvino arrived in modern-day Beijing in 1294 and was eventually joined by other friars. The fiercely anti-Western Ming dynasty began in 1368. Jesuit missionaries arrived in the 16th century; Franciscans and members of other Catholic religious communities worked in secret.

Depending on political events within and outside China, Christianity prospered or languished until 1842 when the First Opium War (fought so the British could bring opium into China) resulted in the first of several “unequal treaties” that guaranteed foreigners broad economic and legal rights at the expense of the Chinese people. Later treaties eventually put Christian missionaries under the protection of France. Some people objected strenuously to this link.

During World War I, many missionaries from Allied countries returned to Europe. The spectacle of Christians fighting Christians in Europe discredited Christianity greatly. Many Chinese people were bitterly disappointed by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, the slight shuffling of colonial territories, and especially the awarding of German territories in China to Japan. Many Chinese people saw the new Communist Party (founded on July 1, 1921) as their best chance to end Western colonial domination.

Foreign missionaries were interned during World War II, depending on their country of origin and who controlled the part of China where they worked. After Mao Zedong proclaimed the People’s Republic of China on October 1, 1949, foreign missionaries were expelled and separate “patriotic associations” were set up to guarantee self-government, self-financing, and self-propagation among Chinese Muslims, Protestants, and Catholics.

The Catholic Church formed Chinese dioceses and archdioceses in 1946, but only three of these 20 new archbishops had been born in China.

Toward the Future

Regarding the 2019 Extraordinary Missionary Month, Pope Francis has written: “I am a mission, always; you are a mission, always; every baptized man and woman is a mission. People in love never stand still: they are drawn out of themselves. . . . Each of us is a mission to the world, for each of us is the fruit of God’s love.”

Pope Francis noted that Pope Benedict XV had reaffirmed that the Church’s universal mission “requires setting aside exclusivist ideas of membership in one’s own country and ethnic group. The opening of the culture and the community to the salvific newness of Jesus Christ requires leaving behind every kind of undue ethnic and ecclesial introversion. . . . No one ought to remain closed in self-absorption, in the self-referentiality of his or her own ethnic and religious affiliation.”

John Kiesler, OFM, who teaches missiology at the Franciscan School of Theology at the University of San Diego, recently wrote: “Just as in 1919 with “Maximum Illud,” the Church is striving to understand, witness, and be converted to Christ in a deeper way through dialogue/mission/life with our brothers and sisters in each culture. The test for us in facing world Christianity is: How do we love and express love in action as well as concrete ecclesial structures to more clearly witness the kingdom of God?”

At the end of every Mass, we are sent out to share the Gospel of Jesus Christ. Would he approve the cultural baggage we are trying to carry as we seek to fulfill his Great Commission?

Father Pat McCloskey, OFM, is Franciscan editor of this publication. Between 1986 and 1992, he served as communications director at the international headquarters of the Order of Friars Minor. He has been fortunate to see the world Church firsthand in several countries.

A Prophetic Voice

Vincent Lebbe, CM (1877‚v940), was born in Belgium, joined the Congregation of the Mission (Lazarists) in Paris, and was ordained in Beijing in 1901, a year after the conclusion of the Boxer Rebellion. He quickly learned Chinese and carefully studied his new country’s culture, dressing in the local fashion and interacting mostly with Chinese Catholics. They helped him found a Chinese Catholic newspaper in 1915.

“Return China to the Chinese, and the Chinese will go to Christ,” he urged insistently. Lebbe advocated passionately for the appointment of Chinese priests as bishops; this was resisted by many people inside and outside his Lazarist congregation—and by many Catholics inside and outside China.

Between 1920 and 1928, Lebbe lived in Europe. Granted Chinese citizenship in 1927, he returned to China the following year, helping to establish a religious community of brothers and one of sisters. When the Sino-Japanese War began in 1937, he was active in nursing wounded soldiers and providing assistance to people displaced by that war. He was captured in 1940 by the Chinese Communists. Imprisoned for six weeks, he was released and died a month later. His cause for beatification was opened in 1988.

Missionary Month Resources

“Baptized and Sent” is the theme of the website of the Society for the Propagation of the Faith (www.missio.org). It offers a wide range of resources to help children and adults recognize and act on their missionary vocation received at Baptism. Modern-day missionaries such as Sister Dorothy Stang, SNDdeN (a 2005 martyr in Brazil), are profiled.