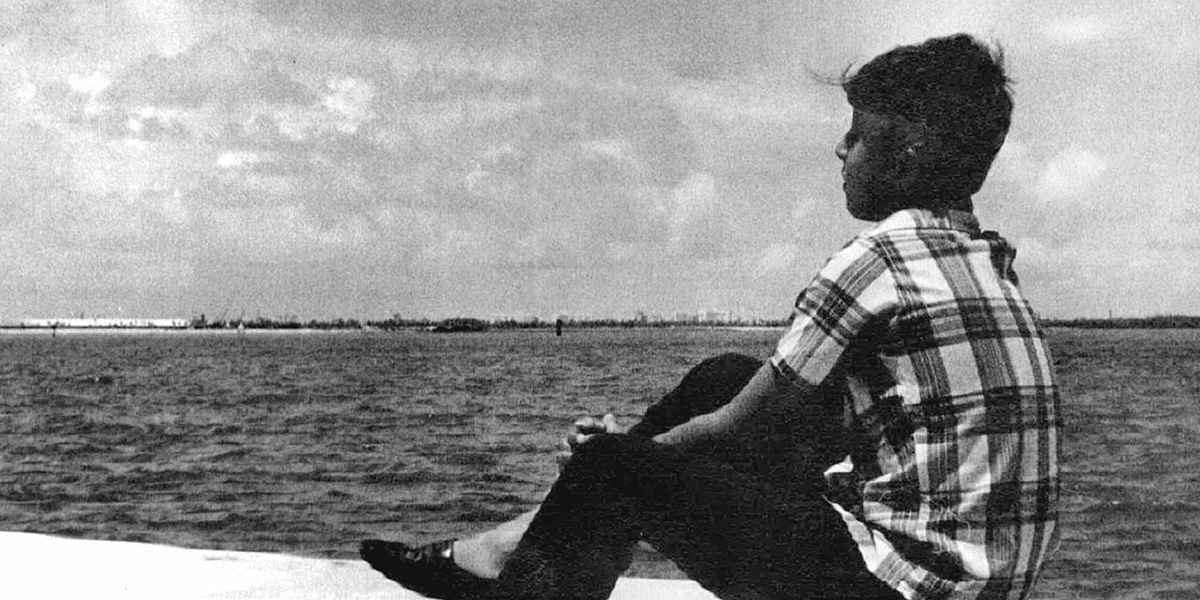

Decades ago brave parents put their children on one-way flights to the United States and freedom.

At the age of 10, Oscar Pichardo left behind his parents, friends, possessions and native land. Oscar and his brother Jesus were among 14,048 unaccompanied Cuban minors between the ages of six and 18 who were airlifted out of Cuba to the United States after Fidel Castro took power. Their parents were not allowed to leave Cuba.

Decades have passed since this grassroots effort nicknamed Operation Pedro Pan took place, yet the details still read like a Communist-era spy novela clandestine underground movement in Communist Cuba, C.I.A. and State Department assistance, an activity kept secret from the U.S. media, and a young Irish priest in Miami coordinating the efforts.

But for Oscar and most fellow Pedro Panes (pronounced “Pah-ness”), as they call themselves, this implausible spy story is first and foremost a story of love; the measure of a love so great, so unselfish, that it moved parents seeking safety for their children to send them unaccompanied to a foreign country.

Procedure Intended to Intimidate

Oscar remembers vividly the hugs and kisses exchanged with his parents at the Havana airport on August 25, 1961 and the intimidating, terrifying hours that followed as he and his brother waited behind the glass wall la pecera, or “fishbowl, ” as the waiting area was known. On the other side of the glass, his parents stood bravely, desperately trying not to show their own suffering, while keeping an eye on the two boys for as long as possible.

“We went into la pecera before noon that day, and we did not leave until close to midnight,” Oscar says. “I sat with my brother but we did not talk. It seemed no one was talking. I’d look for my parents, sometimes having a difficult time spotting them in the crushing mass of humanity pressing close to the glass. I’d smile halfheartedly, but I did not cry. I couldn’t look often.”

Over the next long hours, two armed milicianos, members of Castro’s militia, sat behind a desk in the back of the waiting room and called on people. If you made it this far, you had already filed all required papers and paid all fees to exit the country. The procedure was solely for intimidation. For children traveling alone, it was particularly terrifying.

“I must have been staring too intently,” recalls Oscar, “because an elderly man came to where I was sitting and very quietly told me to look somewhere else it would not be good to bring attention to myself.”

When their names were called, Oscar remembers, “My brother and I were asked a couple of questions and we returned to our seats. I remember looking for my parents [on the other side of the glass] as I made my way to my seat and spotting a look that appeared to be relief on their faces.” When the door leading to the airplane opened, the 10-year-old sought one more view of his parents as he walked out, sending a wave to where he had last seen them.

Oscar Pichardo spent two weeks in Miami’s “Camp Kendall,” one of the refugee camps set up to receive the exiled children, before he and Jesus were sent to St. Joseph’s Home for Children, an orphanage in Green Bay, Wisconsin, where they lived until his parents left Cuba a year later. Now a parent to three grown children and grandfather to one, 60-year-old Oscar views his parents’ decision to send their boys out of Cuba with both admiration and awe.

“You had to live the stark reality that our parents faced and led them to make the hard decisions born out of love and courage to protect their children,” he explains. “When it came time to decide to either submit to the state or send the children to safety, Cuban parents chose freedom for their children sending them unaccompanied to the United States.”

Setting the Stage

Unthinkable. Impossible. Unacceptable. The idea that children would be better off without their parents is simply unimaginable to our 21st-century American experience. Yet this painful scenario has, unfortunately, repeated itself time and again in contemporary world history.

During the Spanish Civil War, in the mid-1930s, thousands of children were evacuated to France, Belgium and England for safety. During World War II, over 7,000 Jewish children were hidden from the Nazis by the French O.S.E. network and were later smuggled into neutral countries. In 1940, during the Battle of Britain, approximately 1,000 British children were sent to the United States for their protection.

In the spring of 1975, some 2,000 Vietnamese children were airlifted to the United States through Operation Babylift as Saigon fell to the Communists, many sent out as “orphans” by their own parents to spare them from a possible bloodbath or starvation.

“Context is the key, and it’s very difficult today to understand what Cuba in 1960 was like,” notes St. Augustine, Florida’s Bishop Felipe de Jesus Estevez, himself a Pedro Pan.

“All the Catholic and Christian schools were closed by Fidel Castro. One hundred fifty priests had been thrown out of Cuba. That gesture alone provides the tonality of the repression. There was a determination by the revolution leaders to repress any dissent or any democratic thinking and it was a totalitarian hard line,” remembers Bishop Estevez.

He was 15 when he left in July 1961, and was placed at St. Vincent Villa, an orphanage in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

In 1960, a year after Fidel Castro rose to power, his regime had already transformed Cuba’s landscape. Property owned by Spaniards, Americans and Jews had been confiscated. Foreign-owned businesses were seized. Neighborhood committees, fashioned after 1930s Nazi Germany, were set up to control and spy on every community block.

Cubans remembered the Spanish Civil War and the 5,000 children who were sent to the Soviet Union for indoctrination and feared the same thing would happen in their country. Parents reasonably feared losing the “patria potestad,” the parents’ right and duty to raise their children, a reality that eventually came to pass in Castro’s Cuba.

A Secret Movement is Born

It all began rather by happenstance.

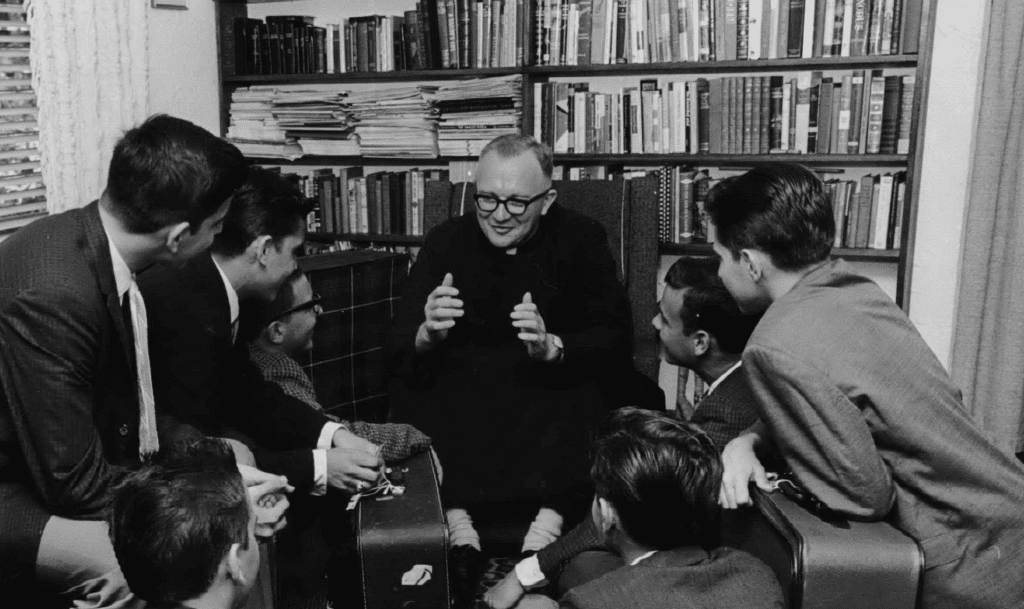

In October 1960, a Cuban boy named Pedro was sent unaccompanied by parents to Miami. When refugee relatives couldn’t care for him, someone brought the 15-year-old to the Catholic Welfare Bureau (CWB, which became Catholic Charities), where Father Bryan Oliver Walsh, director of the bureau, made arrangements for him.

About the same time, a Cuban mother brought two children to Florida’s Key West, dropped them off and returned to Cuba. Walsh quickly realized that the mounting Cuban exodus would likely include many more unaccompanied “Pedros,” and he began to lay the groundwork.

Simultaneously, back in Cuba parents began planning with James Baker, the headmaster of Ruston Academy in Havana, how to get their children out. Baker, an American citizen, traveled to Miami and asked Father Walsh for assistance. A few days later Baker submitted his first list of possible unaccompanied children. The original plan was for approximately 200 children. On December 26, 1960, the first two children arrived: 12-year-old Sixto Aquino and his sister Vivian, 14.

After the United States broke off diplomatic relations with Cuba on January 3, 1961, the Department of State authorized Father Walsh and the CWB to notify parents in Cuba that student visa requirements had been waived for their children, giving the green light for children to travel unaccompanied on commercial flights to the United States.

As word got out in Cuba about the priest in Miami who would look after young refugees, the clandestine exodus network spread out all over the island. Thousands of visa waivers were sent by Miami exiles to their relatives in Cuba, along with the required $25 money order for the round-trip airfare.

Miraculously, Father Walsh and his network of agencies convinced the U.S. media to embrace a “spirit of cooperation” that kept Operation Pedro Pan out of the news for most of its existence. The longer it stayed out of the news, the better the probability that the Cuban government would stay out of the way.

Part of Operation Pedro Pan included visas for the parents left behind. “This fact had to be kept secret,” explains Bishop Estevez, “so that it could take place in spite of the vigilance of the Cuban authorities. It is an important aspect of the program because it reflects a Catholic understanding of immigration, which is family reunification.”

Operation Pedro Pan ended abruptly in October 1962, when the Cuban missile crisis put a halt to commercial air service between Havana and the United States.

The Cuban Children’s Program

What today we refer to as Operation Pedro Pan actually consisted of two distinct facets. The first part was the secret network on the island for getting the unaccompanied minors out of Cuba. Once in Miami, the goal was to connect the children with relatives or friends who could take care of them.

The second element was the Cuban Children’s Program (CCP) run by the Catholic Welfare Bureau, which was responsible for the refugee children who arrived in Miami and had no family in the United States. This continued to operate for many years after Operation Pedro Pan concluded.

Over the 21 months that Operation Pedro Pan was operational from December 1960 to October 1962, 50 percent of the children were reunited with family or friends in Miami. The other 7,464 children were placed in the Cuban Children’s Program led by Father Walsh and the CWB. Eighty-five percent of the children cared for by the CWB were between the ages of 12 and 18.

Operation Pedro Pan was funded by private donations, while the U.S. government funded the CCP’s foster-care program. No children were placed for adoption, since the purpose of the program was to safeguard parental rights.

The main problem became the lack of facilities to care for the minors in the Miami area, so Walsh and the CWB reached out to Catholic agencies across the country seeking foster homes and group-care homes, many associated with religious communities.

The program ultimately placed Pedro Panes in over 100 cities in 38 states.

Seventy percent of Pedro Panes were boys over the age of 12, so special group homes staffed by Cuban houseparents for adolescent boys were opened in several cities, including Wilmington, Delaware; Fort Wayne, Indiana; Albuquerque, New Mexico; Lincoln, Nebraska; and the Florida cities of Jacksonville, Orlando and Miami.

Years later, then-Msgr. Walsh explained his initiative in a 1971 article in the Journal of Inter-American Studies and World Affairs: “What the Catholic Welfare Bureau did was to provide a means for the Cuban parents of that period to exercise their human right to direct the education of their children. No one can deny that separation from one’s family is always traumatic and painful. How could it be otherwise?

“However, at times it is necessary because it is the lesser of the two evils. The real heroes of Pedro Pan were the parents who made the hardest decision that any parent can make.”

The Rest of the Story

Pedro Panes were sent from every province of Cuba. Most were alumni of Catholic schools closed by the Cuban government, and from middle- or lower-class families of various ethnic backgrounds, including black and Chinese. Although the majority were Catholic, at least 500 were Protestant or Jewish.

Eight Pedro Panes became priests, and two of them are bishops: St. Augustine’s Bishop Estevez and Bishop Octavio Cisneros, auxiliary of Brooklyn. There is no data for how many pursued other religious vocations.

Now in their 50s and 60s, Pedro Panes live all over the United States, and even in other countries. Those in the United States learned English, became American citizens and succeeded in school. Some became professionals and entered politics, like Guillermo “Bill” Vidal, Denver’s first foreign-born mayor. Many married other Pedro Panes, though there is no official record of those numbers.

Not all were happy endings, however. Some parents were not allowed to leave for years, and some not at all. The 1962 end of commercial flights between the United States and Cuba began a three-year period during which it was extremely difficult to leave Cuba, impacting many Pedro Pan parents waiting to leave.

But on December 1, 1965, under an agreement between Cuba and the United States, for the purpose of reunification, the Freedom Flights began giving first priority to the parents of unaccompanied minors. Close to 90 percent of those children still under care were reunited with their parents by

June of 1966.

Perhaps the most renowned Pedro Pan is Dr. Carlos Eire, whose memoir, Waiting for Snow in Havana: Confessions of a Cuban Boy (Free Press, 2003), won a National Book Award. Eire was 11 years old when he and his brother Tony left Cuba in 1962.

Eire had a difficult, isolating experience living in a series of refugee camps, foster homes and, later, with an uncle. Ironically, he says, it was because of his Jewish [first] foster parents’ efforts that he stayed Catholic. They “forced me to go to church by myself every Sunday. This gave me a sense of personal responsibility for maintaining my own religion.

“My faith supported me through the worst of times only in an inchoate way. I had no clue, really, as to what faith really meant,” says Eire, who holds the T. Lawrason Riggs Chair in the Religious Studies Department at Yale University. “As I see it now, God was looking out for me, even when I had no clue. I pleaded with God and the saints to protect me from harm.

“But on a daily basis especially in the hellish group home the protection seemed to be missing. It was a dark night of the soul, so to speak. At the worst times, I thought that maybe God didn’t care. But I never gave up believing that God and the saints could help me.”

Eire and his brother were separated from their mother for three and a half years before she was able to reach the United States, and they never saw their father again.

Others, like Juan Pujol, never reunited with their parents. Sixteen when he left Cuba in 1962, Pujol remembers “looking forward to being free, to be able to go to church and practice my Catholic faith without being harassed or persecuted.” But Pujol’s father died, and his mother had to stay to care for her elderly mother. So it was 1979 before Pujol could return to Cuba and see his mother.

Their parents’ sacrifice, says the Miami Beach resident who lived at three different Florida camps during his stint under the care of the CWB, “is to be recognized and commended. They gave us the opportunity to live a full life in a true, free society. I have learned to appreciate every little thing that is given to me, and I have tried to pass this to my children and now my grandchildren.”

That Was Then, This Is Now

Fifty years after the great exodus, most Pedro Panes have come to terms with their parents’ desperate choice. Like Aida Cabrera Morris, they “won’t tolerate” criticism of their parents’ decisions.

Morris, a resident of Almeira, Spain, was only nine years old when she and her 11-year-old brother, Julio, left Cuba on May 1, 1962. In spite of having to live at Queen of Heaven Orphanage in Denver for four years before her parents joined them, and acknowledging what she describes as terrible circumstances for her brother, Morris still applauds her parents’ move.

“It is the most courageous, unselfish, hardest decision that any parent could ever make to separate yourself from your children simply because you know it’s their best chance in life,” she proclaims.

6 thoughts on “No Greater Love: Operation Pedro Pan”

I am a Pedro Pan! Arrived on June 2,1962! I give thanks to my parents for the decision to send me and for the program that helped me ❤️🙏🏻

I am very proud of my parents to had made a decision that it was the best for me.

To have freedom is the best thing that ever happened to me and my family.

Thank you to my mother and the U.S.A. for making me what I am today.

I’m blessed that my mother send me to Thankful to come to America, the land of opportunity. It took me many years to appreciate my mother’s love for me. I lived in an orphanage in Wheeling West Virginia, and ten foster homes in Connecticut. I had a very successful career with a major Aerospace company. I have a beautiful wife married fifty years and two beautiful children. Grateful for my mother’s love.

Having been a Catholic Charities social work intern in the Unaccompanied Children’s program; I recall the account of the horrific scene that two young sisters witnessed before departing Cuba. The program facilitated these brave girls’ foster home placement. The joy of the girls eventual reunification with their parents; as well as the ” loss” experienced by the foster parents; are amongst my memories of the consequences to children of terrible injustice.

Any Peter Pan Kids placed in the state of Washington, OR host families in the state of Washington, or Peter Pan Kids that ended up living and working in the state of Washington? Working on a documentary and would appreciate your help.

I am a Pedro Pan, as is my brother. we were 11 and 16 respectively. I wound up at Kendall, he at Matacumbe a second separation for which I cannot forgive Catholic Charities. My parents arrived in June 1962, but in the meantime we wound up at a foster home with a drunk husband and an uncaring wife and their two little kids (innocent as they were). Another reason why I cannot forgive Catholic charities for making our 9 months a hellish existence in the home of an abusive alcoholic and thief. He even stole money from my bother and I!!! Sickening!

Now 63 years later, I am retired and with two adult kids and a 51 year marriage, in a free country (for now)! All the thanks belong to the unselfish, courageous decision of my parents. We miss them terribly, they did the unimaginable, an incredible sacrifice. No parent wakes up one morning and parts with their children, on a whim!!! It is heartbreaking!

on another note, the article speaks with Oscar Pichardo. Oscar is a good friend of mine and we have been on vacation together a few times. Him and his wife actually drove to our 50th anniversary here in Massachusetts.