You might not think a blind person could be a sports broadcaster, but this man won an Emmy doing it.

The 1950s-era New York dailies, masters of hyperbole when it came to viewing their sports heroes through the what-have-you-done-for-me-lately lens of hero or goat, called it “the shot heard ’round the world.”

Bobby Thomson’s three-run, walk-off home run in the bottom of the ninth inning on October 3, 1951, at the Polo Grounds lifted the New York Giants to an improbable 5–4 victory over their bitter rivals, the Brooklyn Dodgers, giving them a ticket to the World Series as National League champs.

At his microphone perch above home plate, Giants radio announcer Russ Hodges barked out one of the iconic calls in major league broadcasting history: “The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant!”

About 22 miles away—in Jersey City, New Jersey—12-year-old Eddie Lucas stood transfixed. Eddie had pleaded with his father before going to school at PS 22 that Wednesday morning to let him skip class: the decisive World Series play-in game started at 1 p.m., and Eddie didn’t want to miss a pitch.

When Ed Lucas Sr. didn’t relent, his son had to squirm at his desk until the 3 o’clock bell and then rush home to watch what was left of the first nationally broadcast baseball game on the family’s 12-inch, black-and-white Philco television.

When Thomson’s winning homer sailed toward Coogan’s Bluff, Eddie’s father opened all the windows in their Lafayette Gardens apartment and screamed at the top of his lungs.

Eddie changed into his wool Giants jersey and bolted for the door. He was going to the blacktop skating rink to meet his friends and celebrate. He was going to play ball.

Had his protective mother, Rosanna, been at home, Eddie probably would not have been allowed out of the apartment. Eddie was born with limited eyesight. He wore thick glasses to see the blackboard at school. Ophthalmologists told his parents Eddie might lose his sight completely if he ever took a jolt to the head.

That didn’t matter now. The Giants were going to the World Series, and Eddie was going to play in the gloaming.

The pickup game among friends started out with almost full squads, but as the October sky grew darker, more kids had to head home for dinner. Now it was five against five, and Eddie got a rare treat: he took the mound to pitch, something he almost never was selected to do.

Even though he could barely see without them, Eddie took off his glasses and placed them on the ground. The next shot heard ’round the world was a line drive that hit Eddie squarely in the face, which robbed him of his remaining sight and, at the same time, set in motion his incredible journey to become major league baseball’s first blind broadcaster.

Faith, Family, Friends

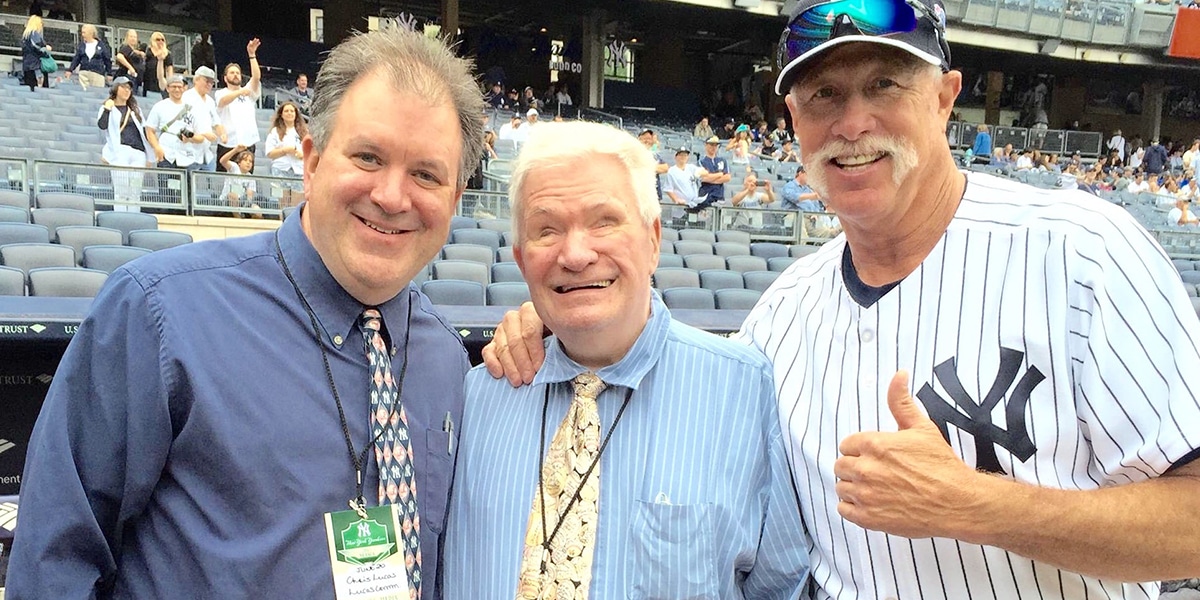

Ed Lucas’ amazing story (cowritten by his son Christopher) of perseverance and living out his Catholic faith is in print—Seeing Home: The Ed Lucas Story; A Blind Broadcaster’s Story of Overcoming Life’s Obstacles—and the movie may be coming soon to a theater near you. “I tell people never to give up,” says Lucas, now 77 and living in Union City, New Jersey.

“I always say there were three things that got me through: faith, family, and friends.” Doctors trying to treat fully detached retinas in the 1950s didn’t have many options. One treatment required Eddie to keep his head motionless for two weeks, so nurses placed sandbags around his head to anchor it from any sudden movement. He ate his meals through a straw. Nothing worked.

On his 13th birthday, his uncle Gene bought him a braille watch, which had a handy popup glass so Eddie could feel the minute and hour hands. Eddie’s father worked as a pressman for The New York Times, and his blue-collar buddies pooled money to buy Eddie an expensive Victrola, which he used to listen to his favorite music, including the rock-and-roll tunes of Johnnie Ray, who went deaf in his left ear at age 13.

When the weather got warmer during the 1952 baseball season, Eddie’s parents rigged an extension cord to the family’s console radio so he could listen to the Giants games outside in the breeze.

In the background, Rosanna used her impeccable penmanship to write letters to Eddie’s favorite baseball stars on the Giants, Dodgers, and Yankees, and many of them wrote back, offering to host Eddie at a game whenever they could. One of the letters went to Yankees shortstop Phil (Scooter) Rizzuto, a diminutive player who had been told he was too short to play in the majors but went on to become the American League MVP in 1950.

In those days, as odd as it might seem today, ballplayers worked second jobs in the offseason to supplement their income. Rizzuto served as a greeter for the American Clothing Shop in Newark.

“I was sort of down and depressed, and my mother read in the paper that Phil was at the clothing store,” Lucas says. “I assume that she had spoken to him because when I went in there with my dad, Phil said, ‘I hear you’re a big baseball fan! You got to keep your spirits up!’ I was only 12 or 13 years old, and I was in awe.”

Before Eddie left the store, Rizzuto handed him his Yankees business card with his home phone number. “You take this and call me any time you want to talk,” Rizzuto told him. Eddie exchanged numbers, and a few days later, Rizzuto was on the phone, telling Eddie he was going to stop by in an hour to take him on a drive so they could grab dinner.

“He just loosened me up and talked about things, and he started to invite me to games,” Lucas recalls. “The one thing he kept encouraging me to do was to get a good education. And we became dear friends — my best friend in life — for 56 years.”

Nuns to the Rescue

Despite Rizzuto’s advice to get an education, Eddie thought it might be out of reach. “My only image of blind people was they had a cane and a cup, begging for money,” he recalls.

But his life changed once again. Every day, his father would take a fresh-air stroll with Eddie around the neighborhood, and after Mass they walked near the Jersey City Printing Company. One day a nun was at the front door, collecting alms, and Eddie’s father dropped a couple of bucks into her basket. As they walked away, Sister Hugh of the St. Joseph Sisters of Peace caught sight of Eddie and wondered why he wasn’t in school.

When Eddie’s father explained that his son’s doctors felt a schoolyard accident might permanently derail any hope of Eddie regaining his sight, Sister Hugh shot back, “That’s no excuse, doctor or not, to keep him from getting a proper education!”

That encounter changed Eddie’s life. Sister Hugh’s community ran the Holy Family School for the Blind, and the nuns there practiced tough love. On one of Eddie’s first days at school, he instinctively reached for the staircase wall with his right hand to help him navigate the steps from the second-floor dormitory to the first floor.

“The way you win in life is by getting

back up when you get knocked down.”

—Ed Lucas

That’s when Sister Anthony Marie swatted his hand away from the wall. “At this school,” she told him, “we don’t put our hands out to feel the walls. We keep them by our sides.”

When Eddie protested that he needed the extra sensory help, Sister Anthony Marie replied: “Isn’t that a shame, Mr. Lucas? You’re not the only disabled person in the world. All of us have challenges to overcome in life and places to go. We are all in the same boat together. I suggest that you pick up your oar, and start rowing!”

At Holy Family, Eddie learned to match separate outfits by color, placing them in a left-to-right grid. When he graduated from eighth grade two years later, along with his diploma he received from the sisters a rosary and a braille Bible.

As he walked out Holy Family’s front door, Eddie stopped, turned around, and ran his hands over the brick wall. Sister Anthony Marie was there.

“Don’t worry about that, Eddie,” she told him tearfully. “We’re going to miss you around here, young man. You are very special indeed. From now on, don’t worry about walls. If you have any in front of you, just knock them down.”

For the last 62 years, Lucas has done exactly that.

Knocking Down Walls

After completing high school at the New York Institute for the Blind in the Bronx, he pursued a communications degree at Seton Hall University in South Orange, New Jersey. There was only one major obstacle: using a combination of public buses, it took Lucas more than three hours each way to get to and from school. He had to travel east from Weehawken, New Jersey, into Manhattan’s Port Authority Terminal, and then west again to Newark, where he walked four blocks to catch another bus to South Orange.

By then, Lucas had been gifted with his first guide dog—a German shepherd named Kay—which made her the only female on Seton Hall’s then all-male campus. “Father Walter Jarvis loved Kay—he named her the queen of the campus,” Lucas says. “I would go to confession to Father Jarvis every Friday. Kay was right there with me. She heard my confession, too.”

In the years since losing his sight in 1951, is friendship with Rizzuto and his invitations to attend Giants, Yankees, and Dodgers games had given Lucas a free pass into the cloistered inner sanctum of baseball. He met every major league star, even those on opposing teams.

On June 14, 1952, he had a chance to talk to Thomson inside the Giants’ Polo Grounds clubhouse about “the shot heard ’round the world”—both of them.

“I think my story sort of shocked him, but we became good friends,” Lucas says.

Since Lucas was on a first-name basis with so many major leaguers, he began interviewing them with an oversized, reel-to-reel tape recorder. His audio reports became prized content for “Around the Bases with Ed Lucas,” which debuted on Seton Hall’s radio station, WSOU, in the spring of 1959. After graduation from Seton Hall, Lucas became an insurance salesman but continued his connection with baseball. It wasn’t always easy facing the jealousy and the biases of big-name New York sportswriters who felt a blind person was taking up space in the locker room and the press box.

Occasionally, players ridiculed his disability. After one game, a visiting player saw Lucas standing by his locker, waiting to interview him. “Here’s what I’m not going to do—talk to a cripple,” the player said. “Is this a clubhouse or a circus?”

What Lucas recalls—even more than the player’s penetrating words—was the deafening silence. No reporter came to his defense. In tearfully recounting the locker-room incident later that night to Rizzuto, Lucas got the same kind of fatherly advice the Scooter had given him inside the Newark clothing store many years earlier.

“Phil told me to turn the other cheek,” Lucas says. “The way you win in life is by getting back up when you get knocked down.”

No one else could ever do what Lucas does near a batting cage. He can stand 10 feet away, hear the crack of the bat, and predict with nearly 100-percent accuracy where the ball is headed.

“I can’t explain it,” he says.

Heading for Home

Lucas says the toughest part of writing his autobiography was recounting the dissolution of his first marriage. When his wife left home, leaving him to raise his two young sons on his own, Lucas called on the three things that matter in his life: faith, family, and friends.

Several years later, his former wife sued and temporarily won full custody of the boys. Lucas was able to successfully regain custody with the help of an expert legal team paid for by friends, including Yankees owner George Steinbrenner.

Rizzuto testified at the trial, explaining how Lucas cared for his children with love, taking them with him to ball games. Lucas regained full custody on September 25, 1980. “That was Phil’s birthday,” Lucas says.

After obtaining an annulment, in 2006 Lucas married Allison Pfeifle, who may be the only person alive who knows more about baseball than Lucas. Rizzuto actually set the ball in motion for their budding romance. Rizzuto had stopped by a neighborhood flower shop and saw that the shopkeeper seemed distracted and down. The owner said her niece — Allison —was having trouble with her vision.

“I have a friend, Eddie Lucas, who is blind,” Rizzuto said. “Maybe he can help lift her spirits. Is it OK if he calls Allison?”

They were married on March 10, 2006, in a small chapel at Seton Hall, and then rode to Yankee Stadium, where they repeated their vows at home plate. It was the first time any couple had ever been married on that spot. “Boss George” Steinbrenner gave the OK and paid for the wedding.

“I guess my story is to not ever give up,” Lucas says.

Especially in the bottom of the ninth.