“Don’t quit,” a Vatican official once told Phyllis Zagano. She took his advice and continues to advocate for ordaining women as deacons in the Catholic Church.

Phyllis Zagano, PhD, perhaps the world’s leading advocate for ordaining women as deacons in the Catholic Church, experienced an epiphany back in 1978.

At the time, she was attending Immaculate Conception Seminary in Huntington, New York, intent on training for ministry and was the only female student in the graduate-level seminary theology program.

Archbishop Jean Jadot, then-apostolic delegate, the pope’s representative in the United States, came for a visit. It was a VIP occasion. Zagano’s fellow students, seminarians studying for the priesthood, were decked out in the house cassock and sash vestments. She wore a yellow corduroy pantsuit and placed herself unobtrusively in the nosebleed seats.

The hosting bishop, the late John McGann of the Diocese of Rockville Centre, New York, noticed her.

“Phyllis, what are you doing here?” asked Bishop McGann, known for his friendly and garrulous banter at public events. Bishop McGann recognized Zagano, as he was a high school basketball pal of her father.

After the ceremonies, Zagano got word that Archbishop Jadot, then a dominant figure in the Church in the United States, one seen as the power behind bishop appointments, wanted to see her.

He asked her what she was doing in the seminary, and she replied that she was studying with a goal of being ordained a deacon. “Don’t quit,” Archbishop Jadot told her. She hasn’t.

Zagano moved on from the seminary in pursuit of other academic achievements, but she hasn’t quit the cause of ordaining women as deacons. The author of scores of articles and five books on the subject, she has remained in the Catholic fold, intently lobbying bishops, priests, deacons, and whoever will listen. She argues that Church tradition allows for ordaining women as deacons.

Even after Pope John Paul II definitively ruled out ordaining women as priests in 1994, Zagano remained undaunted.

Phoebe’s Example

Zagano has made the case that the diaconate is different. The historical legacy indicates that the Church can ordain women as deacons. It is a matter of the Church’s willingness to recapture tradition, not break from it, she argues.

“The diaconate is very clear in Scripture,” she says. The only person with the job title is Phoebe. No one else in Scripture is called deacon. In Romans 16:1–2, Paul commends Phoebe’s diaconal ministry.

For Zagano, the short scriptural reference offers a vein of insight. “Her patronage, one can assume, supported the efforts of the growing Church. With her status affirmed, she is the one not only chosen to carry Paul’s letter to Rome, but also most probably to read and interpret it once she gets to meet with the community there,” Zagano wrote in the Tablet in 2021.

Phoebe’s example lived on in the early Church up to the 12th century. Scripture scholar Gary Macy argues that female deacons gradually became verboten as the Church began interpreting Old Testament purity laws regarding menstruation as forbidding women to lead religious rituals. The entire order of deacons also eroded—largely due to authority and money issues with priests, Zagano says—until it was revived after Vatican II.

While women deacons no longer are active, it’s there in the history, she says. The acknowledgement that women once filled that role has been a linchpin for those arguing that the Church can ordain them as deacons once again, particularly in response to pressing pastoral needs.

Once on the margins, Zagano’s vision may be closer to fruition than ever. Pope Francis has ruled out ordaining women as priests but has said that the diaconate is another question. Zagano served on a Vatican commission to study the issue, spending months researching ancient Church manuscripts, buttressing her arguments. She also talked with bishops and clergy from all over who were eager to describe their need for pastoral ministers.

That commission dissolved without deciding on the central issue. But a second group has been formed and is expected to make a recommendation to the pope. The timetable remains unclear, but many interested in the topic believe that the can won’t be kicked down the road for too much longer.

A Chorus of Voices

At 75, Zagano, a research associate and adjunct professor of religion at Hofstra University on Long Island, remains hopeful. She would like to avoid the fate of Moses, who only lived to see the Promised Land from a distance.

Casey Stanton, 36, is codirector of Discerning Deacons, a group comprised of women who believe they are called to serve as Catholic deacons. Launched in 2021, Discerning Deacons observes the September 3 Phoebe feast day and has surveyed women working in ministry about their sentiments on being ordained as deacons.

Stanton, who served in parish ministry at Immaculate Conception Church in Durham, North Carolina, and worked for a decade as a parish organizer for the US Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Campaign for Human Development, is a graduate student at Duke Divinity School. She describes herself as part of a generation of Catholic women who, as girls, were altar servers and grew up in a world where women in leadership roles are a given.

Women will continue to minister in the Church no matter what, says Stanton, but ordination would serve as a powerful symbol, both for those who would be ordained and for those they serve.

Phyllis Zagano, PhD, a research associate and adjunct professor of religion at Hofstra University on Long Island, has been a leading voice in favor of women deacons for decades. She is hopeful her efforts will bear fruit under Pope Francis.

A study by Discerning Deacons written by Tricia C. Bruce, a University of Notre Dame sociologist, found strong interest in ordination among women in ministry. While some respondents indicated that they would prefer to remain as laypeople, a majority said they were interested in becoming deacons or at least wanted it to be an option.

Ordination, the study concluded, would provide legitimacy to women who often work on the margins of Church life. Such women, noted the study, cope with “how the lack of title, recognition, and authority conferred through ordination results in ambiguity.”

Ordination as deacons would allow for women to routinely perform baptisms, witness weddings, and, perhaps of greatest significance, preach at Sunday Mass, granting their ministry a recognition for Catholics in the pews. The pope’s call to hear from everyone as part of the Synod on Synodality is an opportunity, says Stanton. Advocates of ordaining women deacons are presenting their case in pre-synod dialogues across the country and the world.

Opposition Remains

As the possibility of women being ordained as deacons seems tantalizingly close to many of its advocates, there remains opposition. Some women who have pursued ordination to the priesthood see the diaconate as a token gesture. Others argue that the logic behind forbidding women’s ordination to the priesthood applies to the diaconate as well.

Missionary Servant of the Most Blessed Trinity Sister Sara Butler, who taught in seminaries in New York and Chicago, says that the decision on ordaining women as deacons will be made relatively soon. But, she says, “I can’t imagine it will be yes.” Sister Sara was among the first two women named by Pope John Paul II to the Vatican’s top theology group.

While women served as deacons in the ancient Church, says Sister Sara, the prayers for the ordinations were different between men and women. She questions whether they were selected for the same office. The role of women as deacons, Sister Sara says, was to provide ministries for which men were culturally ill-suited. For example, she says, women served the sacramental needs of female monastic communities and assisted widows.

While ordination advocates point to the substantial record of women in ministry, Sister Sara points to the same phenomenon and asks if ordination would change that reality.

“There’s nothing in particular that will be added,” she says about ordaining women already serving in ministry to the diaconate. The same basic tasks—teaching, ministering to the poor and the sick, organizing church activities—will be carried out regardless of ordination status.

“Holy orders is a single sacrament,” says Sister Sara. And, in a point rejected by many feminist theologians, she argues that “sexual complementarity has sacramental significance in Catholic theology”—namely that mirroring Christ sacramentally is a male function; therefore, the clerical state should be reserved for men.

A Deacon’s Perspective

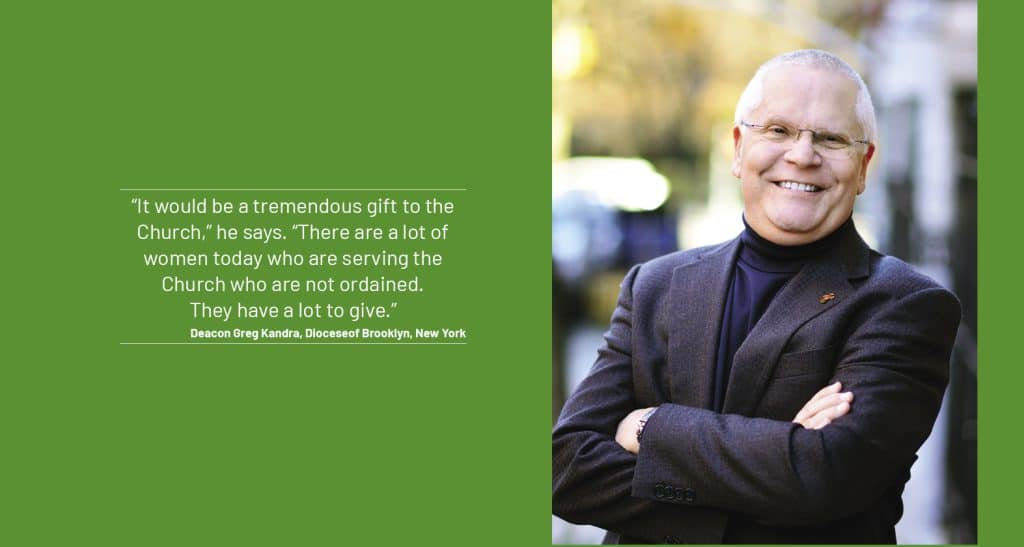

Deacon Greg Kandra, who ministers in the Diocese of Brooklyn, New York, is in regular communication with deacons on TheDeaconsBench.com—a website of commentary on Catholic issues—and as a speaker on pastoral life.

Deacon Kandra supports ordaining women as deacons. “It would be a tremendous gift to the Church,” he says. “There are a lot of women today who are serving the Church who are not ordained. They have a lot to give.”

Their impact would be felt. “You will see women at the altar vested. You will see women preaching at Mass. It would move women into pastoral leadership roles, not just behind the scenes,” Deacon Kandra says.

First, however, he would like to see a greater understanding and acceptance of the role of deacons in the broader Church. “My concern is that the Church needs to get the diaconate right before it brings women into the ministry,” he says.

After Vatican II, the diaconate experienced a renewal. Of the nearly 50,000 deacons in the world, around half are in the United States, a result of the openness to the restored order by American bishops in the 1970s and 1980s.

Still, its acceptance is spotty, even though in many parishes Catholics are familiar with the deacon’s role of preaching, witnessing weddings, performing baptisms, and ministering to the poor. Like priests, deacons in the United States are declining in number and are, on average, older than the rest of the adult Catholic population.

Vatican II, says Deacon Kandra, “left it up to the local bishops and pastors to see how this would work out.” The results have been uneven: Some dioceses offer ongoing formation programs and continue to ordain men. Others don’t. Among the laity, more education about the role of deacons is needed, says Deacon Kandra. Confusion about roles remains. Offering a case in point, he relates how, after a Sunday homily, he was pulled aside by a parishioner who congratulated him on celebrating a superb Mass and referred to the deacon as “monsignor.”

Deacon William Ditewig, former director of the US Conference of Catholic Bishops’ office on the diaconate, supports women’s ordination to the diaconate and coauthored a book on the subject with Zagano.

Like Deacon Kandra, he sees a need to clarify the role of the deacon. Throughout Church history, ordination to the diaconate has been viewed as closely linked to ordination to the priesthood. For centuries, the diaconate has been seen as a stepping stone to the priesthood, a period of mentorship. Today men preparing for ordination to the priesthood are first ordained as “transitional” deacons. This gives them faculties to proclaim the Gospel and to preach at Mass for a year before ordination to the priesthood.

The tradition of ordaining men seeking priesthood as “transitional” deacons—the apprenticeship model—has contributed to confusion about the role of deacons, Deacon Ditewig said. “The deacon is a vocation in and of itself” and not simply a way station to the priesthood, he says.

In addition, the issue of women’s ordination as deacons becomes tied into the priesthood, with the Church’s clear prohibition of ordaining women priests mixed into the debate over the diaconate. Both Deacon Ditewig and Zagano insist that the diaconate is a separate vocation.

Pope Francis, as is his inclination, is willing to let the discussion play out publicly. He has expressed appreciation for the ministry of women in the Church, and the recent flurry of activity around the issue is frequently tied to a meeting he held with religious sisters who inquired about the diaconate.

Whatever the arguments, pastoral needs, such as those expressed at the 2019 Vatican Synod on the Amazon—which focused on a region where many Catholics are ministered to by few clerics—should be the overriding concern, Deacon Ditewig says.

“History gives us lessons, but ultimately it becomes a partial lesson,” he says. The fundamental question is: Who does the Church need now?

Sidebar: Deacons or Deaconesses?

In the world of scholars and activists debating the issue of whether women can be ordained as deacons in the Catholic Church, certain recurring arguments abound. One flash point is language.

Would women ordained as deacons be referred to simply as deacons or as deaconesses? For Phyllis Zagano, who emphasizes that the diaconate is distinct from the ordained priesthood, the answer is deacon, because that is the title granted to Phoebe in Romans 16:1–3.

The diaconate as a vocation was part of early Christian communities, she says. The addition of the transitional diaconate as a training ground for future priests is an addendum of later Church history. “(As) the Church teaches that women cannot be ordained as priest or bishops, it also teaches there is a distinct order of the diaconate,” she writes in Women Deacons: Past, Present, and Future (Paulist Press, 2011).

However, Sister Sara Butler opts for using the word deaconesses. She argues that the Catholic Church has long held a unitary approach to ordination, a role for deacons who can move on to the ordained priesthood. She also points out that the position that women held in the early Church differed from that of men who were ordained as deacons.

The revived diaconate is only 50 years old, and its growth has taken place amid an upsurge in women in pastoral roles. According to a study conducted by the National Pastoral Life Center, lay ecclesial ministers working in parishes outnumber active diocesan priests.

That study estimated that 80 percent of lay ecclesial ministers were women. Whether that work should be recognized by ordination, or remain as a lay ministry, continues to be at the crux of the discussions around the possibility of ordaining women as deacons.

1 thought on “Has the Time Come for Women Deacons? ”

I was a Naval Reservist from 1976-2007, not a retired Naval Officer at the time of my studies at Huntington.

Comments are closed.