The country is struggling with an opioid crisis—but its strongest foothold is in the Midwest. Armed with their faith, these individuals are fighting back.

Ryan Dattilo estimates that he knows at least 100 people who have died from a drug overdose. These people were not just numbers—they were friends, siblings, sons, daughters, and parents. “The drugs take over, and they make you do things that you never think you would do,” explains the 36-year-old Cincinnati resident.

“I would hurt my mom and I would do all these things, but that never meant that I didn’t love my mom. It didn’t mean that I was choosing drugs over her—that drugs were more important. It just meant that I was in the grips of an addiction,” Dattilo says.

In 2017, President Donald Trump declared the opioid crisis a national emergency. While actual usage is impossible to estimate accurately, well over 70,000 people died of an overdose in 2017, according to the National Center for Health Statistics, which is operated by the Centers for Disease Control. Overdoses killed more Americans under 50 years of age than any other cause.

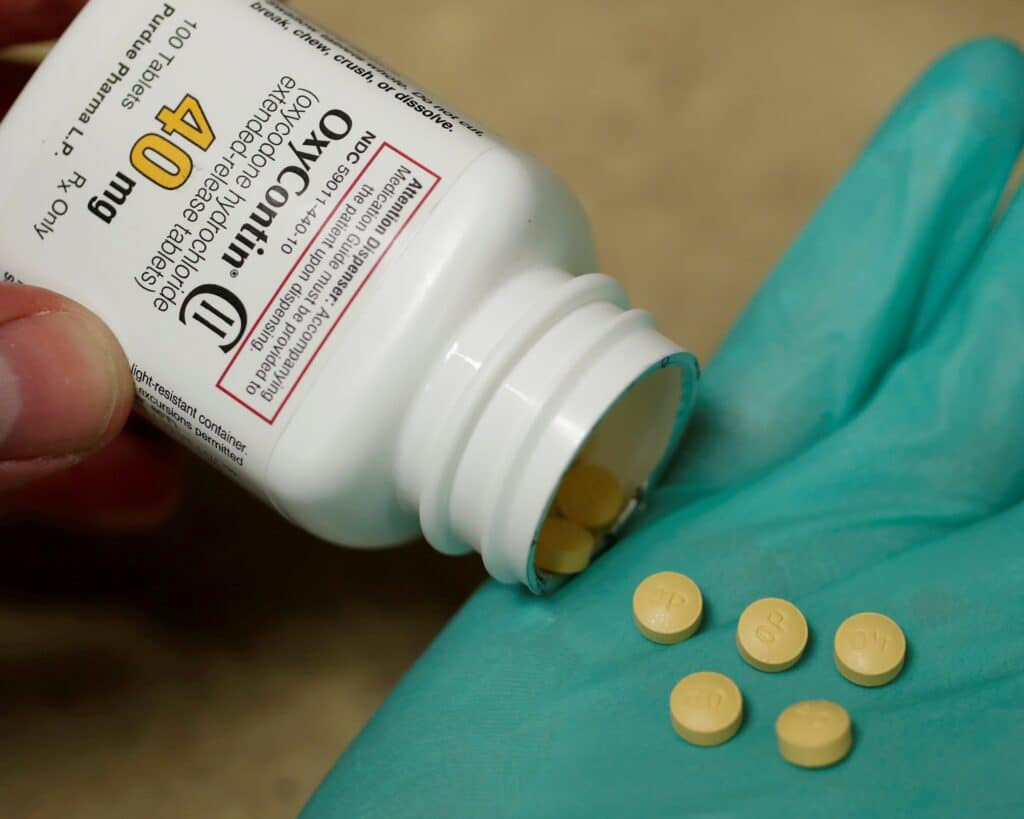

Opioids, a broad category that has come to include heroin, methadone, fentanyl, and some prescription painkillers such as OxyContin, act on receptors in the brain that regulate the body’s pain and reward system. They mimic natural chemicals created to reinforce behavior, which makes these substances extremely addictive.

In the national crisis, West Virginia, Ohio, and Pennsylvania are at the epicenter. These three states had the highest rates of death due to drug overdose in 2017, and those rates had increased significantly from the previous year.

Dattilo grew up right in the middle of the epidemic. He became addicted to heroin after a slow transition from alcohol—which he started at 14—to marijuana, and eventually to prescription opioids and crack cocaine. Once in the grips of the addiction, he could not function without regular doses of the drug. When a dealer was not available, or Dattilo did not have the money to spend, he quickly became “dope sick.”

“You feel like you have the flu times 100,” he describes, “diarrhea, fever, clammy skin, achy joints. But you know that once you get what you’re after, you’re going to be fine.” Dattilo is convinced that these withdrawal symptoms keep people chained to substance use even if they want to quit.

“This is a disease,” emphasizes Sandi Kuehn, president of the Center for Addiction Treatment in Cincinnati, the facility where Dattilo ultimately sought help.

“As a disease, it should be treated medically, and the medical piece of it doesn’t necessarily have to be medication, but we should be treating it as a disease. You can’t arrest yourself out of it,” Kuehn says.

The Center for Addiction Treatment is one of the few medical programs accessible without health insurance. For $20, Dattilo received a 30-day in-residence treatment that included a medical detox, support groups, and help with resources such as housing and employment. Most treatment centers cost between $2,000 and $25,000, which is prohibitive for those whose financial resources have been decimated by their addiction.

“I know people who were going to jail on purpose, trying to get into the drug court because they can’t pay for treatment,” Dattilo says. “[And the courts say], ‘We’ll get back to you in six months.’ The reality is people can be dead in six months out here.”

The Bigger Picture

For every person struggling with substance use, there are dozens of family members and friends struggling alongside them. Addiction can have devastating effects on everyone connected to the individual, straining relationships and destroying families.

“We were so far apart, on different pages, with how to deal with it and not knowing how to deal with it,” says Tina Garera, 57, whose marriage was nearly torn to shreds when a loved one became addicted to multiple substances.

Tina and her husband, Tony, have helped found several Northern Kentucky branches of the national support group Parents of Addicted Loved Ones (PAL). In PAL meetings, family members of persons with an addiction come together for camaraderie and mutual support. One particular group meets twice a month in the Diocese of Covington’s Catholic Charities building. The Gareras facilitate group discussions, with as many as 20 people sharing current struggles and offering suggestions to each other.

“We need to be in recovery too,” Tina says, outlining the shame and isolation that confronted their family because of the stigma associated with addiction.

“Except for working, we didn’t go out of the house much. We didn’t take vacations because we had to be there for our loved one,” Tony adds. “[Our family member] started getting better when we started getting better.”

Caring Communities

The Gareras say that the support group meetings—coupled with a divine prompting to return to church and ask God for help—are what ultimately saved their marriage. Unfortunately, many church communities are not welcoming to those struggling with addictions and their families.

“It has to start at the pulpit. It has to start with the pastors and the priests and the deacons,” Tina says. “They have to let families know that it’s OK to talk about this—that it’s going on in this church, and that they have to learn to love people right where they are. I guarantee you, sitting there in that congregation, every single person has been affected one way or the other by this epidemic.”

In West Virginia, where substance use is at its highest, a simple presentation broke the silence and brought about concrete actions, which saved lives.

Ellen Condron, the parish nurse at All Saints Catholic Church in Bridgeport, suggested that her parish host a “community conversation” about substance use in their social hall. A professor of psychiatric nursing at Fairmont State University, she had learned that children were coming to school without food or clean clothes. Addicted parents were simply incapable of tending to their children.

“A lot of the people in our community had no idea how bad it was,” she says. “It was like a third-world country within our community that we didn’t know about.”

“The other day a woman I didn’t know came up to me and said, ‘You have to keep doing what you’re doing,'” Condron recalls. “She gave me a hug and told me about her relative who had been helped and was now drug-free.”

These conversations have led to other bright spots, both large and small, in addressing the epidemic. All of the local schools were provided with washers and dryers so they could wash the clothes of children whose parents wrestled with addiction. Several local churches provide food to these same children on Fridays so that they will have something to eat over the weekends.

Condron, now recognized as a community expert, also met with their representative from Congress about the crisis. Their meeting led directly to the activation of the Office of Drug Control Policy for West Virginia. The office closely follows a model that she and other activists created.

‘I Believe You Can Get Better’

Condron said that church communities already have the power to stem the epidemic. Worshippers just need to “let the spirit guide.

“Within churches, you have a core group of people like we did,” she explains. This group can form the basis for activism: gathering resources, organizing details, distributing information, and finding areas of need.

“We seem to have created a following with what we’re doing. And I think it’s because we support each other and we know that this is important,” she says.

Back in Cincinnati, Kuehn describes a church group that organizes childcare for those who are working toward recovery. “When someone needs to go into treatment, they may not have anyone reliable to watch their children while they are in a residential program,” she says. They vet people in the community who are willing to step in and help addicts with childcare.

These people say, “‘Yeah, I’ll do that for you for a year, because I believe you can get better. And whatever stability I can give your child is something that could affect them, which then could affect, in a positive way, our community,'” Condron says.

Little Things Count

When one person takes action, the ripples of relief are impossible to overestimate. During the worst part of his struggle with addiction, Dattilo was living on the streets. He camped beneath a Cincinnati bridge for three years and had no means of a steady food supply or access to basic hygiene.

“I didn’t see an exit for myself. I knew I deserved better, I knew I wanted better, but I just didn’t know how to connect the dots from A to B to actually get out of there,” he recalls.

On the streets, he came into contact with workers from a local nonprofit called Downtown Cincinnati Inc. In the below-freezing temperatures of January 2018, one of the workers gave him a ride to the treatment center. He was admitted into their residential program the next day.

“I looked like an absolute shell of a man. You look at Tom Hanks in Cast Away—that can give you the mental image of me. I smelled so bad, it was embarrassing,” he says.

Even with new clothes and regular showers, Dattilo said it took time for his hygiene to recover. Some of the other residents at the treatment center avoided contact with him. But it only took one counselor, a woman named AJ, who had herself been in his shoes, to restore his dignity and hope.

“She’s a beautiful lady, and she made me feel welcome. She made me feel like anything is possible. I felt like she was seeing my potential—she wasn’t seeing me as I was. And that is the first person who had believed in me in a very long time, who showed me that there was hope,” Dattilo says.

Dattilo graduated from the center and has been living in recovery ever since. He now works for the very same organization that picked him up off the streets and volunteers as a peer advocate at the Center for Addiction Treatment. Ultimately, he wants to have a job working on the streets, spreading hope to the homeless.

When asked how church communities can help those who are struggling with addiction, Dattilo’s request is simple. “Pray,” he says, adding that God’s providence is the reason he is alive today.

“If you feel comfortable enough to stop and have an actual conversation with a homeless person or a drug addict, let them know that Jesus still loves them. Let them know that they are not forgotten about. Let them know that they exist, that they matter, that there’s hope,” he says.

The Gareras and Kuehn echo the same sentiment: In this epidemic, faith matters. Those who embrace spirituality are more likely to recover from their addiction. Those who have a spiritual center are more likely to withstand the stresses that come with having a struggling loved one. Hope is possible: Christ’s people are called to be the light, especially in the darkest depths of despair.

“When society and people walk by you and ignore you every day for a long time, you just really lose your self-worth,” Dattilo recalls from his years on the streets. “If you improve one person’s day, you’ve made that person’s day,” he continues. “That changes the world realistically. You made life better for one human being.”

The Opioid Crisis at a Glance

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), more than 130 people in the United States die every day from opioid overdose. “The misuse of and addiction to opioids—including prescription pain relievers, heroin, and synthetic opioids such as fentanyl—is a serious national crisis that affects public health as well as social and economic welfare,” the site reports.

Below are more statistics from the NIDA.

- 21 percent of patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain misuse them.

- 8 percent develop an opioid use disorder.

- An estimated 4 percent who misuse prescription opioids transition to heroin.

- About 80 percent of people who use heroin first misused prescription opioids.

- Opioid overdoses increased 30 percent from July 2016 through September 2017 in 52 areas in 45 states.

- The Midwestern region saw opioid overdoses increase 70 percent from July 2016 through September 2017.

- Opioid overdoses in large cities increased by 54 percent in 16 states from July 2016 through September 2017.

Patron Saint of Addicts

In June 1979, then-Pope John Paul II visited the cell in the Auschwitz concentration camp where St. Maximilian Kolbe—prisoner 16670—was confined. Kolbe, he proclaimed, is “the patron saint of our difficult century.” It was not until three years later, though, that he officially canonized the Franciscan, who had given his life for a fellow prisoner.

The pope’s words could not have been more prophetic for our world today. The struggles with addiction that are currently ravaging our world are calling out for a spiritual guide. That guide is Maximilian Kolbe.

The saint is the patron saint of those suffering from addiction, perhaps due to his death on August 14, 1941, following a lethal injection of carbolic acid at the Auschwitz concentration camp.

Kolbe suffered more than 15 days of torment before succumbing to that lethal injection. He died on August 14, 1941, at the age of 47, a martyr of charity. Pope Paul VI declared Father Kolbe Blessed on October 17, 1971, and Pope John Paul II canonized him a saint on October 10, 1982. St. Maximilian is the patron saint of families, prisoners, journalists, political prisoners, drug addicts, and the pro-life movement.