Archbishop Oscar Romero may have been murdered decades ago, but his presence lives on in El Salvador.

Last March, as the city of San Salvador began its week-long commemoration of Archbishop Oscar Romero’s death, the souvenir T-shirts were abundant, worn by locals and visiting pilgrims alike. They were hot sellers in the stalls surrounding the downtown cathedral. There, Romero’s body lies in a crypt where everyday campesinos (native farmers) come, light candles, touch his tomb and metaphorically whisper in his ear, beseeching favors.

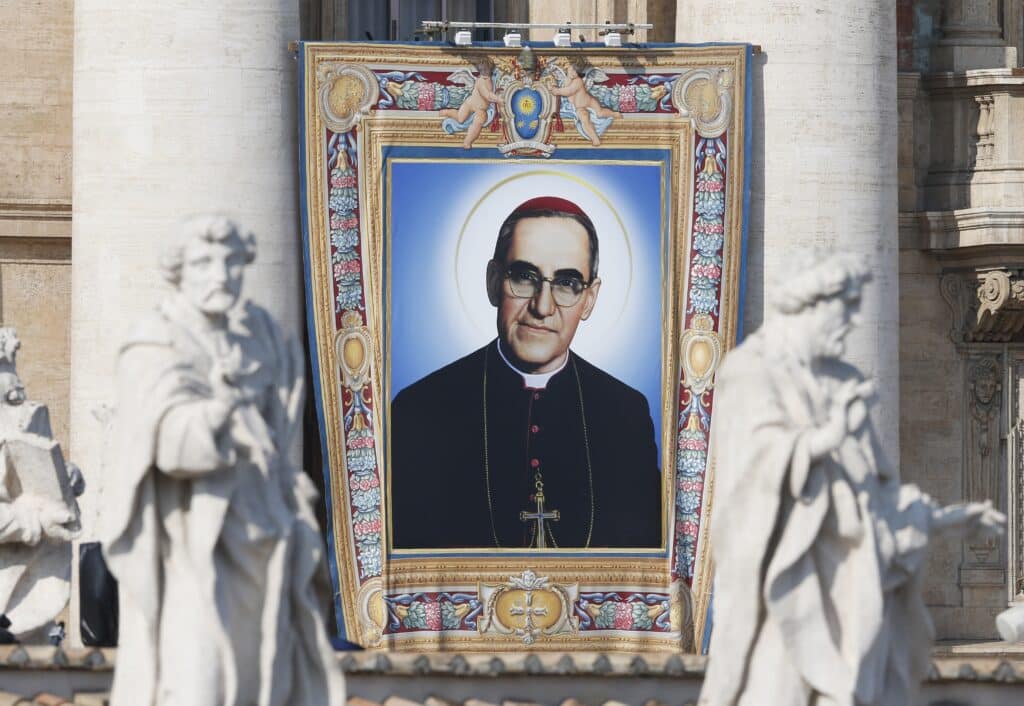

“As a Christian, I do not believe in death without resurrection. If I am murdered, I will arise again in the Salvadoran people,” reads one popular shirt. The shirt bears the archbishop’s words and his bespectacled image above a map of the New Jersey-sized nation where more than 75,000 people perished in the civil war of the 1980s.

Romero, killed by soldiers while celebrating Mass at a hospital chapel on March 24, 1980, was an atypical victim, if one judges by his elevated position. But he joined thousands of others far less famous, from human-rights lawyers to union organizers to campesinos, as well as three North American sisters and a laywoman missionary, whose deaths have never been legally addressed in El Salvador. No one has ever been convicted of the murder of the archbishop.

Romero remains alive in the hearts of Salvadorans. Three decades later, tens of thousands crowded the downtown streets in a march to the cathedral, shouting, “Viva Romero.” Long an unofficial national hero, he has been formally embraced by the country’s new government. At the country’s only airport, international visitors are welcomed with an official mural depicting the archbishop.

President Mauricio Funes, elected in 2009, joined last year’s commemoration march, the first Salvadoran president to do so, and has formally apologized for the government’s role in the murder. During his inaugural address, he asked that his administration be judged by the standards set by Romero. While Romero’s prophetic witness stirred divisions within the Church when he was alive—some of his auxiliary bishops cautioned that he went too far in defending the poor.

Reaching a New Generation

Even the younger generations, who did not experience the civil war or know Romero personally, invoke his legacy. The streets are filled with murals depicting the man, often with quotes from his many homilies and radio talks.

“Christ and Romero are the same to us,” says Mauricio Lemus, a lay leader at Santa Cruz Church outside San Salvador. At 33, Lemus was a child when the archbishop was murdered.

Mario Salvador Diaz, 21, a student at the national university, was born nearly a decade after Romero’s death, but has read countless books and seen films about the archbishop. His parents told him stories of the impact the archbishop had on their lives. Diaz helped construct a mural outside his parish, Our Lady of Guadalupe, dedicated to the memory of the archbishop.

For younger Salvadorans, who comprise the vast majority of the population, Romero “has become the spiritual support of those who have their hearts broken. He has become the saint of El Salvador and the Americas,” says Diaz.

“The people believe Romero is still with them,” says Dennis O’Connor, director of CRISPAZ, a Cincinnati-based organization devoted to forging links between American Christians and Salvadorans. “Thirty years after his death, he remains legendary.”

A Romero Revival

Jesuit Father Dean Brackley ministered in New York’s South Bronx until being called to teach theology at the University of Central America in San Salvador after six of his fellow Jesuits and two women helpers—a mother and daughter—were murdered by Salvadoran military soldiers in 1989. That event was the last great spasm of violence directed against the Church during the civil war. Father Brackley has noticed a revival in Romero interest and public favor over the past decade.

For many years, says Father Brackley, “Romero was absent from public discussions, his memory suppressed by the media.” This year’s commemoration was an indication that the resurrection of Romero’s legacy has come full circle.

In El Salvador, he has been embraced as a Christ figure, a national hero, his memory kept alive through the efforts of those who suffered during the civil war.

Faith and Politics

The view of Romero in El Salvador today is much like that of African-Americans toward Martin Luther King, Jr., says Father Brackley. Dr. King is seen in both a Christian prophetic and political context. From a Church perspective, Romero’s canonization process continues. Still, that is expected to be a long-term project, for the archbishop’s actions and words remain controversial. While almost all Salvadorans concede that Romero was a man of saintly proportions, that legacy, as it often is with popular saint-like figures, continues to be contested.

“There is a struggle over Romero and his legacy,” says Father Brackley. Some argue that “Romero’s political critique is not essential to his sanctity.” He was, in this model, a man of prayer and simplicity, devoted to the Church and his people, eschewing the offer of a mansion in a secure gated community to live in a simple series of rooms on the grounds of a hospital for children with cancer.

This faction points to a man, a carpenter’s son born in 1917, who faithfully served the Church, with a devotion to the popes honed through service as a young priest in wartime Rome. In his pursuit of peace and reconciliation, he was willing to criticize all factions, including the rebels, in a conflict that became internationally colored by the Cold War. Some say that Romero’s reputation for personal piety was hijacked by those with a political agenda.

“His prayer flowed from his love and defense of the poor, his belief that the Church must walk with the poor,” says Father Brackley, who has written extensively on the Romero legacy and frequently greets international visitors who come to the University of Central America, wanting to learn more about the legendary figure.

“Romero points the Church forward. This is the way we have to go. We have to walk with the crucified people today. Romero understood that, if it was not good news for the poor, it was not the gospel,” he says.

Compelled to Be a Prophet

While emerging as an international figure, Romero cannot be understood without understanding the context in which he lived. El Salvador is, while small, densely populated—it now has more than six million people. It has frequently been wracked by violence. Today, it is the criminal drug gangs who wreak havoc.

In Romero’s day, soldiers—in large part financed by the U.S. government—and militia death squads wrought terror on large sections of the population. Most Salvadorans continue to live in poverty; many have escaped to the United States, Canada and Europe in search of work.

At the time of Romero’s appointment as archbishop in 1977, those who clamored for change openly expressed disappointment. Romero was perceived at the time as timid and allied with the wealthy. He was, critics said, a man chosen so as not to disturb the powerful, who saw the emergence of liberation theology and the growing movement in the Church for a “preferential option for the poor” as a threat.

Romero was considered a safe choice, a quiet intellectual who would not prove a problem. His visage evoked a quiet placidity. Few saw him as a man who would disturb the status quo in a Catholic country where a small group of families controlled almost all the wealth. They crushed any efforts at rebellion by controlling the government and the military.

But that analysis proved wrong. Romero, says Father Brackley, began as an archbishop simply dedicated to advancing the agenda of the Church. But he quickly discovered, in the circumstances of his time, that he was compelled to be a prophet.

How Did This Happen?

Some say the roots began early, in Romero’s quiet upbringing in a small provincial village. He was born poor, lived among the poor and sympathized with their struggles. But other factors as well galvanized him into action.

Romero had spirited discussions with a friend and Jesuit priest, Father Rutilio Grande. Father Grande had long been identified with groups advocating change, and Romero thought his friend was pushing too aggressively. But once Father Grande was murdered soon after Romero became archbishop, the quiet, scholarly Church leader emerged as a prophetic lion.

His homilies became more pointed. At a time when the press in El Salvador was heavily censored, his Sunday homilies, broadcast over the radio, offered hope for those who wanted recognition and condemnation of massacres in the countryside, as government troops and militias swept through whole villages, killing thousands. Romero heard the stories as he listened to peasants who trekked, sometimes with donkeys in tow, to their archbishop’s office, pleading with him to say something.

So he did. Romero’s condemnations of the violence became bolder toward the end of his three-year tenure as archbishop. He challenged wealthy Catholic families, who were well-known for public displays of piety but financed death squads. He emphasized the Church’s call for the rights of workers to organize, and decried the poverty that caused so many Salvadorans to leave the country in search of work. He called upon the leaders of the only country formally dedicated to Jesus, the Savior, to live up to its namesake.

Many think he sealed his fate when, days before his murder, Romero clamored for soldiers to “cease the repression” and lay down their arms, because “no soldier is obligated to obey an order contrary to the will of God.” The statement was seen in some quarters as a call to mutiny.

While the social and political legacy of Romero is still debated, his sanctity is still celebrated in traditional Catholic ways. The crowds who come to the crypt at the San Salvador cathedral are a testament to the Catholic belief in the Communion of Saints. They murmur quiet prayers, touch his coffin and beseech him for favors. Popular religiosity merges with Romero’s prophetic witness without contradiction. His tomb is always covered in flowers brought there by the people he served, as well as by international visitors.

A Miracle?

Dennis O’Connor knows very well about Romero’s impact, even 30 years after his murder. While visiting El Salvador in 2008, O’Connor came down with severe pains. He hurried home to Cincinnati, where he underwent surgery that removed cancerous tumors from his colon, and was told by his doctors that he might not have lived if he had waited much longer. Recovery was expected to be arduous, marked off in years.

Meanwhile, in El Salvador, a group of visiting pilgrims from St. Margaret of York Church in Cincinnati joined hands and prayed at the Romero crypt for O’Connor’s recovery. Something happened: O’Connor was back at work in a few weeks, surpassing any medical expectations. Today his cancer is in remission.

“I think that my case was miraculous,” says O’Connor. “I was given a second chance because I was working with the people of El Salvador. There is no doubt in my mind that there was divine intervention and a whisper in the ear from Romero.”

Still a Strong Presence

In any case, there has been a miracle of resurrection regarding Romero. He is acclaimed as a national hero. Perhaps his killers thought someday they would be hailed for ridding El Salvador of a controversial Churchman by marching into a hospital chapel and taking out the man who had proven so troublesome to those in power. Perhaps they thought they were ridding the turbulent Central American region of a dangerous revolutionary leader. If those who plotted the murders are still alive, they dare not offer themselves for public scrutiny.

By contrast, Romero’s image, rare for a bishop anywhere in the world, is emblazoned on T-shirts, akin to a rock star. It is expected that the anniversary of his death will become a national Salvadoran holiday. Despite the controversy that still surrounds him, he is expected to be canonized someday, a sign of personal piety and prophetic witness for all the Americas.

The crowds continue coming to his crypt. On the exact day of the 30th anniversary of the murder, in the pulpit in the floor above the archbishop’s tomb, U.S. Cardinal McCarrick spoke of Romero at a Mass as if he were still there, as if death never really did come for the archbishop.

“Your death was not the end of your mission or your ministry. It was only the beginning,” he told a cathedral packed with foreign visitors, the country’s president and the Salvadorans who embraced their champion in life, death, and resurrection.

Key Dates in Oscar Romero’s Life

August 15, 1917

Oscar Arnulfo Romero y Goldámez is born in Ciudad Barrios, a Salvadoran mountain town near the Honduran border.

April 4, 1942

Romero is ordained a Catholic priest in Rome.

1944

Romero returns to El Salvador, where he serves as a parish priest.

February 23, 1977

Romero is appointed archbishop of San Salvador.

March 12, 1977

Romero’s friend and fellow priest Rutilio Grande, S.J., i

assassinated, an event that profoundly affects Romero.

March 23, 1980

In a homily, Romero urges soldiers to disobey orders that go against God’s will: “I ask you, I pray you, I order you in the name of God to stop this oppression,” he pleads. Many feel it was this homily which sealed Romero’s fate.

March 24, 1980

Archbishop Romero is shot and killed while celebrating Mass.

1981

Romero is awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

March 24, 2010

Thirty years after Romero’s assassination, El Salvador’s President Mauricio Funes offers an official state apology for Romero’s assassination.

May 23, 2015

Romero is beatified.

October 14, 2018

Romero is canonized.

To learn more, read our blog Oscar Romero: Pastor, Peacemaker, Saint.