God knows best, and, while we’ll still hope for a favorable surprise, we can hardly do better than not only being resigned to whatever God permits but even beforehand to thank Him for His mercifully loving designs.

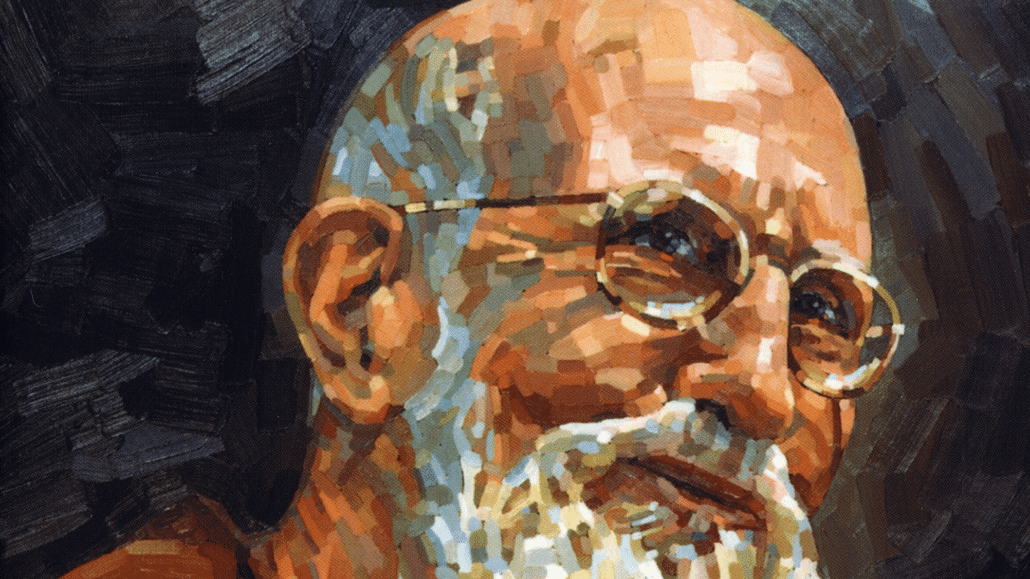

—A letter written by Solanus Casey

Solanus Casey’s struggle to find his place as a priest and member of the Capuchins followed him, in a sense, to his first assignment. Sacred Heart parish in the New York suburb of Yonkers, where Solanus arrived in 1904, looked down from a hill onto the Hudson River. The view from his window reminded Solanus of his childhood home in Wisconsin.

Solanus’s simplex status presented a problem to the pastor of Sacred Heart, Father Bonaventure Frey. Father Frey, who had cofounded the Capuchin order in the United States and established the parish, had admitted Solanus into the Capuchin novitiate seven years earlier in Detroit. Now he was faced with the question of how to employ an apparently holy priest who could not do the regular parish work of hearing confessions and preaching at Masses.

Father Bonaventure ended up putting Solanus in charge of the church’s sacristry and of the altar boys. In this and in his future assignments, Solanus, though a member of the clergy who had studied theology for ten years, performed the tasks of unordained brothers.

Solanus was strict but fair with the boys, quick to reproach them for lack of reverence in their tasks but also eager to reward them for good service with walks to the park, stops for ice cream and subway trips to the beach, Manhattan, St. Patrick’s Cathedral and baseball games. The boys knew he cared about them, and they loved playing baseball with the catcher who refused to wear a mask.

The Holy Priest

After a couple of years Father Frey retired, and a new pastor, Father Aloysius Blonigen, came to Sacred Heart. Quite soon he gave Solanus a new assignment: that of porter for the monastic community and the church office.

As porter Solanus answered the door, tracked down friars who had visitors and handled messages and packages. He swept the sidewalk in the morning and talked with people in the neighborhood. Sometimes he ran inside and came out with food to give away. Other times people asked him to visit an afflicted person at home. He became known as “the holy priest,” as in “Go get the holy priest,” when someone was in need.

Especially when people were sick, more and more often someone came to the monastery and asked for Solanus. People noted his sensitivity and gentleness. “If you were sick, he hurt with you. He was very compassionate. He could say a few words to you and you would be perfectly at ease.”

Solanus demonstrated an openness to all people, including non-Catholics. At this early point in his ministry, his visiting took him to non-Catholic homes where Catholic servants who belonged to the parish were employed. In time Protestants, Jews, people of many faiths and races as well as nonbelievers came to see him. While inviting non-Catholics to consider the “claims” of the Catholic faith, he respected people’s religious commitments and encouraged them to live up to those commitments. Commenting on his definition of religion, “the science of our happy relationship with God and our neighbors,” Solanus wrote, “There can be but one religion, though there may be a thousand different systems of religion.”

One woman saw a rabbi with a cane come to visit Solanus every week. “Now he had faith and I was full of doubts,” the woman said. “But when I saw him walk away without the use of his cane, then I believed.”

The other doorkeepers embodied this same ecumenical spirit. André invited everyone to pray at the oratory, including Protestants and Jews. Many Protestant military personnel attended Pio’s Masses during World War II; he was reportedly friendly with all of them (though he had little patience for Jehovah’s Witnesses) and never pressured them to convert to Catholicism. “If they intend to convert,” he said, “the Lord will show a way.”

In the context of everyday acts of concern and service, Solanus’ gifts began to make themselves known. He once went to visit a woman who had given birth and was suffering from a life-threatening infection. He immediately asked for holy water. The family had none, so he sent Carmella Petrosino, a girl who acted as a go-between and translator for Solanus and the Italian immigrants in the parish, to her home to get some. When she returned, Solanus prayed over the sick woman and blessed her, “and from then on the woman got over her infection and lived a long time afterward.

During the World War I years, he developed the habit of visiting families in the parish who had men going into the armed forces. Solanus would pray with the family for their safety and bless the departing men. Sometimes he would predict their safe return.

The Sisters of St. Agnes, who served the parish, noticed this ability to predict the future. They would say to one another, “If in June, when you go back to the motherhouse in Wisconsin, Father Solanus says, ‘See you in September,’ you will be coming back; if he just says ‘Goodbye,’ you will be transferred.”

Solanus just seemed to know. As his ministry developed, he gave prophetic words of encouragement to many: “Tomorrow at 9 o’clock,” “in two days at 3 o’clock,” or “within a short time,” “if you have faith these troubles will disappear.”

Perhaps this prescient gift served Solanus’s own well-being when his parents celebrated their fiftieth wedding anniversary. He made the long trip to Seattle for the event, where he celebrated Mass with his two priest brothers, Maurice and Edward. Aprogram of tributes, songs and poetry followed.

It was the last time Solanus would see his parents. Two years later his father died while saying a prayer to Our Lady of Sorrows. Three years after that his mother died of pneumonia during the noontime ringing of the Angelus bells. Though Solanus could not be present for their funerals, the memory of their anniversary celebration was perhaps a great comfort. And the circumstances surrounding their deaths served as reminders of the gift of faith they had given him.

The Front-Door Ministry

In July 1918, after Solanus had served for fourteen years at Sacred Heart, his superiors transferred him to a Capuchin parish in lower Manhattan, Our Lady of Sorrows. His new assignment began the same day as the transfer. His journey from the country to the suburbs to the city was now complete.

Father Venantius Buessing, his new superior, made him the sacristan, as he had once been in Yonkers, and also director of a parish young woman’s group, or sodality. Though Solanus could not preach formal homilies, he could deliver short exhortations, known as “ferverinos,” to this group on the Scripture for the day. Solanus worked hard on these “homilettes,” frequently speaking of God’s love and the challenge to accept and respond to it. About fourteen of the homilies have been preserved.

At Our Lady of Sorrows Solanus had more time to himself, and these three years in the heart of the city were a kind of retreat for him. He studied Scripture and read piles of books dealing with the saints, the church fathers and mystical writings. He also devoted himself to personal prayer.

The provincial chapter of 1921 moved Solanus yet again, sending him to the Capuchin parish of Our Lady, Queen of Angels in Harlem, where he resumed the duties of porter. Starting in Yonkers, but especially in Harlem and later when he returned to Detroit, his front-door ministry took on the form that it would have for the rest of his life.

Solanus sat in an office near the door. People came and waited to talk with him. In their time with him they told him of their problems: sick loved ones, marital troubles, estranged family members, unemployment, looming surgeries, drinking problems, depression, anxiety. Invariably Solanus listened with attention. He sometimes laid his hands on a sick person and prayed. In other cases he promised to pray for the person’s needs, which he did in the chapel after he had fulfilled his other responsibilities.

After hearing about a difficult situation, sometimes Solanus looked away into space. It seemed he would receive an intuition. He could see into the problem, what the need was and how it would turn out. Returning to the person, he would speak very gently and with great compassion, offering advice and comfort.

Solanus encouraged his visitors to “do something to please the Dear Lord”8 as a sign of faith and commitment, like helping the needy, going to confession, returning to regular prayer and participation in the sacraments. He often persuaded them to join the Seraphic Mass Association (SMA). Founded in Switzerland at the turn of the twentieth century, the association raised money to support Capuchin missions throughout the world. In exchange for a small contribution, Capuchins worldwide would remember SMA members in Masses and other prayers.

Solanus saw many values in the SMA. It supported the Capuchin missions, encouraged appreciation for the benefits of the Mass and the mission of the church and gave the people he talked with a way to give as well as ask for something. So many new SMA memberships came in through Solanus’s work that he became an official promoter of the association. People tended to want Solanus rather than another friar to sign them up for the SMA, as more favors seemed to flow for the members he enrolled.

Solanus also visited inmates at a Harlem prison. Now he went to minister to, not guard, the prisoners, who were largely poor African Americans. He said Mass, talked with them, gave them newspapers and Christmas cards and administered “the pledge”—a promise not to drink for a certain time after they were released from jail.

Answers to Prayer

Solanus’s ministry at the front door produced results. Sick relatives became better. Estranged spouses reconciled. Personal problems resolved themselves. People were coming back to Solanus to tell him about these favors and blessings. “Thank God!” and “God is good!” Solanus would say. He reminded them that the blessing came not from him but from God, and through the many Capuchin priests around the world who had offered Masses for their intentions.

Solanus had been noting answers to prayers as early as 1901. Perhaps he had some inkling of his gifts even as a novice, when he wrote in his notebook, “Beware of congratulating thyself on the blessings wrought through thy medium.”

When the Capuchin provincial, Father Benno Aichinger, visited the friary in Harlem in 1923, he told Solanus to begin keeping a record of his visits with people. Ever obedient and dutiful, Solanus acquired a notebook and wrote under the first entry: “Nov. 8th, 1923….Father Provincial wishes notes to be made of special favors reported through the Seraphic Mass Association.” For example, a woman enrolled her sister, who suffered from severe pain, and later reported, “Thank God and the good prayer society, I’m feeling fine.”10 Every third or fourth entry recorded a similar positive outcome.

By 1956 Solanus had filled seven of these “Notebooks of Favors Reported” with more than six thousand entries. At that time one of Solanus’s assistants, Father Blase Gitzen, had so many reports of cures through the intercession of Solanus that he “eventually threw them away.”

The number of Solanus’s visitors continued to grow, but in July 1924 he found out that he was to move from New York to the Capuchins’ provincial headquarters in Detroit, St. Bonaventure’s Monastery. In the peremptory ways of religious life in those days, he received the news on July 30 and had to be in Detroit on August 1. He packed immediately and was on the train the next day.

At St. Bonaventure’s Solanus became an assistant to the longtime porter, Brother Francis Spruck, and picked up where he had left off in New York. It didn’t take long for large numbers of people to begin coming to talk with him. Soon the friars left the door unlocked and put a sign over the doorbell that said, “Walk In.”

Some days Solanus’s time in the office lasted from 7:00 AM to 10:00 PM.“From morning to night he would be listening to persons with worries and cares and disturbances, and with all the humility and all the patience in the world he would give them fatherly advice and often enkindle their courage and hope and reassure them in a brief time their troubles would be finished or counsel them to be resigned to suffer with Christ.”13 Solanus’s evening prayer for people stretched his day out to as much as eighteen hours.

Though thousands of people poured out their hearts to him, Solanus could not give absolution for sins because of his simplex status. Instead he worked out a system with one of the other priests, such as Father Herman Buss at St. Bonaventure’s. After hearing a petitioner’s story, he would say, “Now go over to the church and I’ll call Father Herman and he’ll go over to hear your confession….Now you told the whole story. Just give a résumé to Father Herman. He will understand that you talked to me and he’ll give you absolution.”

Following God’s Plan

Visits with Solanus in his office frequently concluded with his giving a blessing. In the words of Brother Leo Wollenweber, “Standing—a tall, thin, almost gaunt figure—he would place his hands with their crooked arthritic fingers on the head of the person and softly pray. Sometimes he might playfully tap the person on the head or cheek” and give the person a smile, accompanied by his “twinkling blue eyes.”

“When he was speaking with you,” another Capuchin said, “you felt that he was constantly Godcentered, on fire with love for God, and constantly Godconscious, seeming always to have his eyes on God. He seemed to see everything as flowing from God and leading back to God.”

Solanus never seemed to lose patience under the crush of visitors, despite the long hours he kept. And his patience spawned patience in the people waiting to see him.

They knew that he had time for them, and he treated each as if he or she were the most important person in the world. Even when people had to wait for hours, they remained peaceful. “Somehow the sense was that Solanus would take as much time with everybody as was needed, and that somehow this was all part of God’s plan.”

Rarely did Solanus speak of the hardships of his ministry. In a letter to his past assistant Brother Leo, he qualified his “complaint” by pointing out that his calling far outweighed the pain he experienced: “Even though fraught with dangers, it has many advantages, if only we be of good will, and cooperate with the graces never failing on God’s part and [that of] our Blessed Mother. Sometimes of course it becomes monotonous and extremely boring, till one is nearly collapsing.” But with typical humility Solanus added, “In such cases it helps to remember that even when Jesus was about to fall the third time, he patiently consoled the women folk and children of his persecutors, making no exception.”

“That poor sinner Solanus,” he once told Brother Leo, “more than anyone else gave me trouble as long as I was in St. Bonaventure’s.” Deflecting the focus from those who burdened him with their troubles, he once asked someone to “Breathe a little [prayer] for the conversion of the poor sinner Solanus who makes so little progress in faith, hope, and charity.”

1 thought on “‘Thank God Ahead of Time’—A Look at Solanus Casey”

The life of Father Solanus is truly amazing. May God always bee glorified in the minds of all who hear about him and all the good that God did through him to others. If we could all love as he loved the world would be healed of its infirmities.