Did anyone really know Henri Nouwen?

His students thought they did. His colleagues thought so. Those who saw him give presentations know what they saw: a tall, physically awkward yet highly animated performer, his unkempt hair all over the place, arms flapping as his hands gestured outwards and upwards. Such energy! Others remember something else, the anguished, prostrated, silent man they saw deep in prayer.

His readers certainly believe they know him, as every reader thinks they know the writers they read. When we read an author’s work, we befriend them and are confident that we know them intimately and in ways that no one else could possibly understand. We say, sometimes silently, “It doesn’t matter what you think, I know how this particular author speaks to me, and that’s all that matters.” In this, we are creating the author that we are befriending. It’s easy when that author shares personal matters, whether in fiction or not.

After years of nonfiction publishing, Henri thought about creating hybrid works that mixed different forms of writing. Although many of his books are based on his journals, they offer relatively brief glimpses into his life, despite his personal, direct, and intimate tone. To read Henri is to discover an uncertain pilgrim on the prowl, hungry for a sense of the experience of home. He’s frequently anguished, and he’s always in need of reassurance. His successes hide the shadows of deeply felt vulnerability that nagging uncertainty about feeling loved. Whenever Henri makes a discovery, it takes the form of a great life-changing and life-settling moment—though not always a permanent one. And in that, Henri becomes so wonderfully and recognizably human.

A Biographer’s Dilemma

The challenge for any biographer is how to paint such a profoundly elusive human chameleon. As Henri’s biographer, I began by scooping up the fragmented details I could glean by talking to people who knew him, either through their direct contact with him or with his work. All biography is like that, built through conversation.

It’s the same when we read one. To read a biography is to have a conversation with our friends: the dead. That is how the British biographer Michael Holroyd describes the collaboration between the reader, the writer, and the subject of a biography. The novelist Julian Barnes knows that these conversations are often based on flimsy information. In his playful novel about the challenges of writing a biography of the elusive French author Gustave Flaubert, Barnes says that biographies are filled with details that just happen to get caught in a net that is “a collection of holes tied together with strings.”

Once that imprecise net is pulled out of the water the biographer “sorts, throws back, stores, fillets, and sells.” Barnes asks the reader to consider what the biographer doesn’t catch because “there is always more of that.” When the biographer Janet Malcolm was asked about writing her biography of the American poet Sylvia Plath, she compared her work on it with that of a professional burglar, “breaking into a house, rifling through certain drawers…and triumphantly bearing [the] loot away.”

Our friends, the dead, depend on us. Joseph Conrad wrote that those who are dead “can live only with the exact intensity and quality of the life imparted to them by the living.” It’s up to us, then, the living, to keep them alive somehow in the stories we share. Unfortunately for the dead, it’s not always the most supportive friend who gets to tell the story. As the famous Oscar Wilde quip attests, no matter how many disciples there may be, “it is always Judas who writes the biography.”

In one of his books about biography, Nigel Hamilton says “scratch any serious modern biography and love will be a predominant motif.” We all know that some love stories don’t turn out well. Biographies, like memoirs, can be filled with acts of revenge. An editor friend of mine recently shared the opinion that when men write memoir or biography, they want to try to set the record straight, finally, and often by getting even. In contrast, the editor suggested that when women write memoir or biography, they tend to seek a new understanding of a particular relationship or experience. Literary biographer Hermione Lee says it doesn’t matter whether the biographer is male or female; the most important point is what a biographer does not include. She sides with Julian Barnes when she says that biographies “are full of things that aren’t there: absences, gaps, missing evidence, knowledge or information that has been passed from person to person, losing credibility or shifting shape along the way.”

‘Vital Presence’

I never met Henri. The Henri I have come to know is the prism-like person filtered though the memories of others, some of whom are indeed literal and figurative disciples of his. The disciples I met are the ones who, unlike Judas, did not slink away in the darkness. They stayed until the meal was over, and many attended the burial.

As a member of the growing international community of people who write about the life of Henri Nouwen, I like to think that I am neither Judas-like nor a burglar. I think of myself an observer at a distance who in the course of this project has discovered a friendship with someone who is dead. The Henri I befriended is the person I came to know as I listened to people who knew him well. In preparing a radio documentary about him for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation with Michael W. Higgins, we heard friends and colleagues and former students as they painted their portraits with words. In these conversations with the living, twenty years after his death, Henri was a vital presence.

The more I listened, the more Henri shape-shifted, just as Hermione Lee suggested. In her analysis, biographical portraits are not fixed for very long. Mary Carruthers, in her fascinating books about memory in the pre-print medieval world, cautions us about the fragility of memories and the unreliability of documents. She advises us to interpret both carefully and to consider that what may be more truthful about them is not always their content: “That is what they remember, but rather their form and especially their ability to find out things, that is how they cue memories.” What was said and how it was said becomes the story. The transcripts of the interviews, like the medieval manuscripts that Carruthers describes, “do not resemble databases so much as they do maps for thinking and responding.”

Like every biography, what follows is a thinking and responding work in progress. A generation from now, as more letters and recollections surface, the contours of the mapped portrait of Henri will continue to evolve with more thinking and more responding.

My book Henri Nouwen: His Life and Spirit offers a composite portrait of Nouwen, who was born January 24, 1932. This portrait is assembled from observations by a small but close group of people who knew him well, and from my own reading of his books. The conversations were mostly about the professionally engaged “Henris,” and this is why I pay more attention in this biography to his experiences on this side of the Atlantic than his early years in the Netherlands. I try, though, to capture something of the spirit and intensity of his life, recognizing the impossibility of trying to capture in words the entirety of any person’s life journey.

As people began telling their Henri stories, time and again, there would be a sudden rush of emotion and a necessary pause for a moment to recover as they struggled to continue. Their voices were altered, stirred by memories of someone no longer in their life yet still a vivid presence. They needed to recount their stories and impressions with accuracy and respect. The stories I listened to contained recurring images: Henri’s sudden changes of mind, new challenges and old contradictions in collision, his clear strengths and the sometimes hidden weaknesses of this gifted individual, a creative artist who was also a wounded healer.

Listening takes effort and sometimes calls for subtle change of footwear as well as attitude, as Pope Francis explained recently.

Listening means paying attention, wanting to understand, to value, to respect, and to ponder what the other person says. It involves a sort of martyrdom or self-sacrifice, as we try to imitate Moses before the burning bush: we have to remove our sandals when standing on the ‘holy ground’ of our encounter with the one who speaks to me. Knowing how to listen is an immense grace, it is a gift which we need to ask for and then make every effort to practice.

As with any conversation, there were asides and diversions that explained certain situations. My book does the same thing with vignettes in each chapter. These detail certain events that had especially lasting consequences. I move through the sixty-four years of Henri’s life as chronologically as possible, and in each chapter, I focus only on Henri’s books from that particular time period.

Biographical Friendship

I am thankful for the opportunity to discover a biographical friendship with Henri and the realization of the depth and continuing reach of his influence. This work is neither hagiography nor biographical hatchet job. I do not offer it as a positio by stealth for Henri’s cause for beatification and canonization. I leave that for others. Like Henri’s Letters to Marc, this work is written “as much for myself as for you,” the reader. Think of it as a letter that begins with “Did I ever tell you about this person who…?”

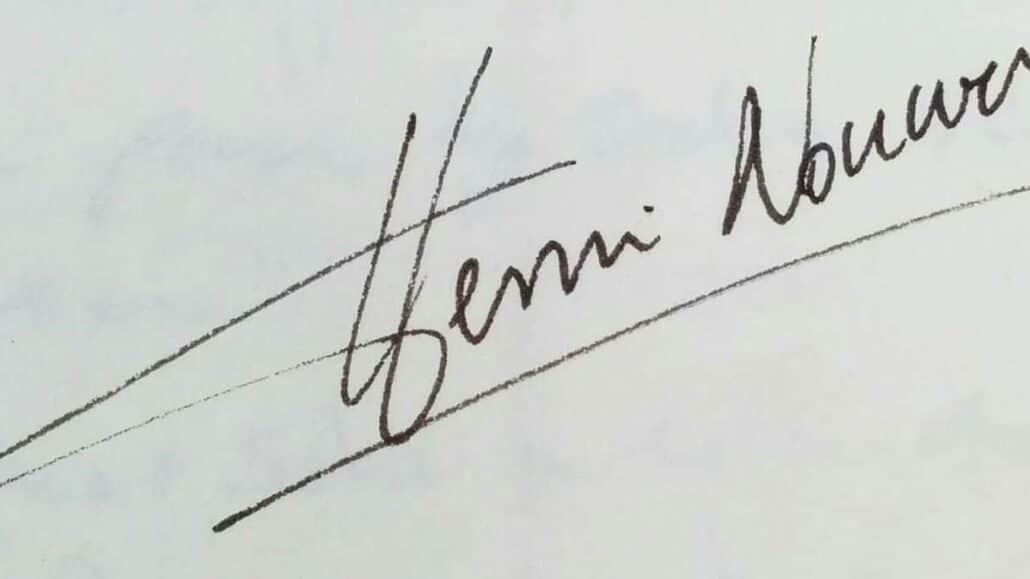

I use this image of a letter because of their importance for Henri. He received 16,000 of them, according to Gabrielle Earnshaw at the Nouwen Archive in Toronto. “Letter writing was something he took very seriously,” she says. “He wrote about letter writing and the importance of letter writing as a form of ministry, as a form of friendship, as a form of retaining relationship, as a form of connection with community.”

Knowing that people he didn’t know chose to write to him caught him by surprise. These letters had a direct effect on him, and he said they influenced not only his prayers but even his breathing and heartbeat. He also wrote three enduring books in the form of letters: Letters to Marc (his nephew), A Letter of Consolation, written in 1982 to his grieving father, and Life of the Beloved, written in response to a challenge from a secular Jewish entrepreneur, writer, and friend. Fred Bratman asked Henri to write something useful about the spiritual life for him and his friends. He writes it as if he was addressing a dear friend he has come to know “as a fellow traveler searching for life, light, and truth.”

Henri was a fellow traveler in a rapidly changing Catholic culture. Richard Sipe, who first appears in my book as a Benedictine and fellow student with Henri at the Menninger Foundation early in their careers in psychology, will reappear later in a very different context. One night, as I took a break from writing, I went to the movies and was surprised when Richard Sipe suddenly made an appearance in the feature film Spotlight, which is about the Boston Globe’s coverage of the Boston archdiocese’s sexual abuse scandal. The film is based on the work of the Boston Globe’s investigative team and the articles that resulted in their book, Betrayal, which also references the work of Richard Sipe.

The team asserts that the problem in Boston was not unique, but “a microcosm of a festering sore on the body of the entire Church. If to some defenders it seemed like merely a brushfire, it was to others the greatest conflagration to face the Church in generations. It spread across the North American continent, stretched across to Europe, and scandalized Australia and parts of Latin America.” You don’t see Richard Sipe onscreen; it’s an actor, Richard Jenkins, who provides the voice of the California-based expert on celibacy and formation who takes part in teleconferences with the newspaper’s team of journalists. In the midst of that clamor about credibility, leadership, and moral authority, I was reminded how Henri’s spiritual authenticity stands apart as it also continues to engage people.

I think the actor who plays Sipe in that film would enjoy playing Henri. That voice! Dutch rolling and trilling and as smooth as Edam. There are some funny and really moving examples of Henri’s voice in the Toronto archive. As I worked with them, I was fascinated by the sound. Dutch-speaking Henri spent most of his adult life living and writing in English, but if you listen to any recording of his voice from the 1970s and those from the 1990s, his accent never changes. Unlike many people who, like me, once they arrive on this side of the Atlantic, begin to drift toward a mid-Atlantic vocalization, Henri sounds decidedly and consistently Dutch. Henri’s Dutch biographer, the late Jurjen Beumer, said it was the same whenever Henri spoke Dutch. “It’s amazing! Some people go to the United States for maybe a year or two, and they love to have an American accent. Henri, when you hear him talking in the Dutch language, even after thirty years, you wouldn’t say he had ever lived in the United States or Canada. He felt very connected with his own country, I think.”

As I researched many biographies to see how they worked, I found one that, like this one, was written about someone twenty years after the person’s death. It was Kevin Bazzana’s biography of the Canadian pianist Glenn Gould, who incidentally was also born in 1932. Some key phrases grabbed my attention because of the way they also apply to Henri. Gould, like Nouwen, died young. His “untimely death at the age of fifty” shocked people and “stimulated new, widespread demand for his work.” Bazzana then addresses the issue of legacy. “Since his death, the literature has grown exponentially…major biographies…books of photographs and reminiscences by people who knew [him], surveys of his work…more focused studies…conferences—scholarships, testimony, hagiography.” And especially this: “His posthumous reputation has been enhanced by the aura of the explorer, the rebel, the outsider that surrounds him.” Bazzana’s Gould “demonstrated even after death, a remarkable ability to capture people’s imaginations, sometimes with the force of revelation.” Isn’t that Henri?

Before leaving Glenn Gould, he shares something else with Henri Nouwen in addition to 1932. By the time they were just six years old, each knew the career they would pursue. “As early as age five or six,” Bazzana tells us, “Glenn had decided he would become a professional pianist.” Henri tells us, “Since I was six years old I have wanted to be a priest, a desire that never wavered except for the few moments when I was overly impressed by the uniform of a sea captain.”

As I read more biographies, I encountered several biographical techniques I wanted to avoid; for example, leading with a set of predetermined theories and forcing every aspect of a life to conform to them. Or identifying family traits as if dealing with the ingredients of some kind of genetically determined cake. I am not that kind of biographical baker. Instead, I looked to fiction for guidance. In the final section of Middlemarch, the novelist George Eliot gave me the approach that seemed to be the one to follow. She writes that it is the unfolding of a life story through time that captures our attention.

Every limit is a beginning as well as an ending. Who can quit young lives after being long in company with them and not desire to know what befell them in their afteryears? For the fragment of a life, however typical, is not the sample of an even web: promises may not be kept, and an ardent outset may be followed by declension; latent powers may find their long-awaited opportunity; a past error may urge a grand retrieval.

I trace Henri’s journey through its ardent outset in religious life and the emergence of his latent powers as a compelling speaker and writer. He stumbled several times before a long-awaited opportunity presented itself and which made the final decade of his life such a grand retrieval.

New Generation of Admirers

When he died in 1996, the generation that knew his works mourned him, and a new generation began to discover, in his absence, a thoughtful writer who managed to talk about difficult things concerning spirituality and faith, and ultimate meaning and death, in ways that are easily understood. With biography, though, even as new material surfaces, we still must start again from the beginning, as Kierkegaard (who will make cameo reappearances in chapters 2 and 7) cautions: “No generation begins at any other point than did the preceding generation, every generation begins all over again.” As that first generation mourned Henri in stories about him, they helped the next generation learn about him, and they also did what Michael Holroyd suggests people have done throughout history:

By recreating the past we are calling on the same magic as our forbears did with stories of their ancestors round the fires under the night skies. The need to do this, to keep death in its place, lies deep in human nature, and the art of biography arises from that need. This is its justification.

This, then, is an invitation to another generation of readers to begin a conversation with one of our friends, the dead. As you get to know him, you might find that he’s a member of that sometimes ragged but always brave parade of inspiring individuals in the Christian tradition that we know as the communion of saints—even if they may not be fully signed members of that prestigious club. Yet.