Police officers are more likely to die by suicide than be killed by criminals. A retired Catholic Charities executive and others are working to change that.

Brian Cahill has never been a cop, but burnished in his psyche is a troubling slice of data about police officers. No matter how tough the city or how crime-ridden a neighborhood, psychological risks are more likely to bring down a cop than the most hardened criminals, says Cahill, retired executive director of Catholic Charities in San Francisco.

The fact is, more police officers kill themselves than are killed by criminals. In the first 10 months of 2019, 188 police officers across the nation died by suicide. Two years before, 140 police officers killed themselves, while 129 died in the line of duty.

Particular police work and certain cities have been suicide hot spots. In New York City in the first 10 months of 2019, 10 police officers took their lives. Six in a similar time period killed themselves in Chicago. The rate is even higher among corrections and border patrol officers.

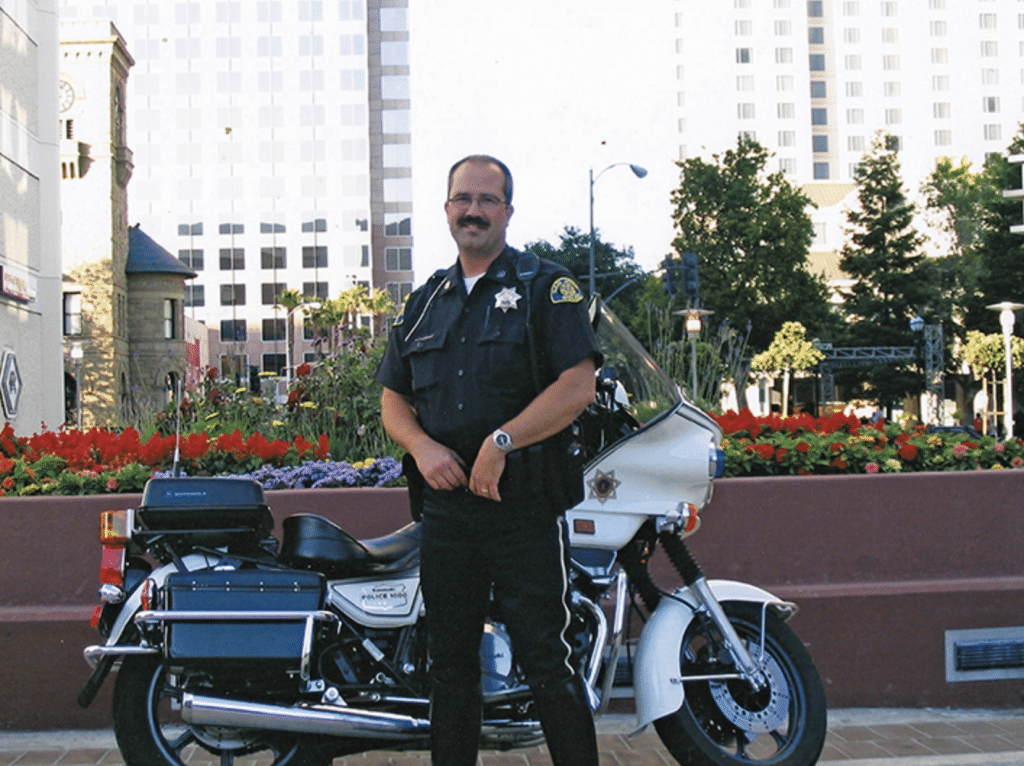

John Cahill, a father of two, served as a motorcycle officer in San Jose, California, until his death in 2008.

A Mission Born of Personal Tragedy

Cahill is a veteran of social service leadership, but he comes to the issue with more than a professional stake. In 2008, just days after his retirement party, he got word that his son, John, a San Jose, California, police officer, 42 years old and the father of two, killed himself.

“I’m just the father of a cop who lost his way,” says Cahill. Like many other family survivors, he has taken it upon himself to make something good come out of personal tragedy. He has studied the issue and spends time in police departments around California and the country, warning police officers and their supervisors to be wary of signs of despair among fellow cops.

“You guys have to train for the hidden risks,” Cahill, a frequent suicide-prevention lecturer for police audiences, often tells them.

For the past eight years, he has tried to shed light upon those risks by making suicide prevention among cops a mission. Cahill speaks regularly to officers in San Francisco and San Jose, and he wrote a book in 2018 about his son’s death, titled Cops, Cons, and Grace: A Father’s Journey Through His Son’s Suicide. His work with Catholic Charities gave him the background and skills to immerse himself in a sensitive issue. “I do think that as a social worker all my life, once I started to climb out of my initial grief and pain, it was a logical and natural inclination to look to how I could help other cops and their families avoid what happened to my son,” he says.

San Francisco police are required to take 40 hours of ongoing education every two years. Cahill gets a half hour of that time to spread his message of the need for self-healing as well as signs to watch out for among colleagues. His theory, and that of others in the field, is that just as it takes a village to raise a child, it takes an involved community to watch out for the mental health of police officers. The model of the lone cop fighting through personal demons doesn’t work.

Theories abound as to why police officers are vulnerable to suicide. Some point to their access to guns; however, others note that often the method of killing does not involve a firearm. Cahill sees the psychology of a police officer as a major factor.

“They are used to bringing control out of chaos, ” he says, noting that they are often the first on the scene of a crime or a tragic accident. When that ability to control personal problems—such as drinking, money problems, or a marriage conflict—begins to slip, cops become vulnerable.

Another factor is the taciturn culture of police departments, especially suspicion that those outside the blue wall cannot fully comprehend the strains of the work.

Police are often reluctant to ask for help, says Cahill, noting that there is a credo among many officers that doing so is a sign of weakness. In some departments, admitting to mental illness or addiction can mean squandering a chance for promotion or being assigned to restricted duties.

But police departments across the country are beginning to change, trying to encourage officers to seek help when needed.

One such department is San Francisco, where Art Howard has risen to the rank of sergeant over an 18-year career. He is now part of the department’s employee assistance program.

“Suicide is killing more cops than bad guys [are],” he says, talking to a reporter on a rare day off. He echoes Cahill, whom he has worked with on employee assistance programs, when it comes to analyzing the whys of police suicide. “In law enforcement, we take control of situations,” he says. “That’s part of our job. When we feel out of control, we feel depressed.”

A common issue among police officers is alcoholism, often aggravated by post-traumatic stress disorder, much like veterans who have been through war. In the jargon of therapy, too many stressed police officers are self-medicating via drinking and other drugs.

A Lifetime’s Trauma in One Day

Experts on police mental health note that the nature of the job creates special challenges. For most people, a violent event may happen once or twice in their lives. For many veteran officers, simply going to work may result in an encounter that could prove traumatic.

A study by the Ruderman Family Foundation noted that a typical police officer encounters 188 critical incidents in a career, traumatic events such as the beating of a child, a deadly car accident, or seeing a corpse.

The nature of police work is not normal, says Howard. Exposure to violence and accidents, sometimes resulting in death, is part of a police officer’s work. “That could be a Monday for us,” he says, noting cops’ repeated exposure to trauma can create adrenaline rushes that are hard to get down from.

Howard notes that some military veterans working for the San Francisco Police Department who have experienced combat and who have served as officers tell him that the pressure is often more intense in police work, that the exposure to trauma is even more intense.

What develops, says Howard, is a “hypervigilant stance that officers get into by being on guard all the time.”

The go-it-alone attitude is beginning to crack as departments across the country promote mental health initiatives. One of his goals, says Howard, is to encourage officers to look out for themselves as well as their fellow officers. The goal is to encourage them to seek therapy, to promote a culture that can overcome the stigma attached to seeking help. The department trains 300 officers in peer support, helping them learn to identify warning signs. “Everything we’re doing is suicide prevention,” says Howard.

That approach is now more common across the country.

Chicago police officer Cindy Phillips began a program she calls STAR (Suicide Trauma and Recovery), intended to bring police officers together to talk out personal issues. It’s a program she would like to extend around the country.

Phillips, a 19-year police veteran, began STAR after her 17-year-old daughter Emily killed herself. Emerging from her own grief, she wanted to help others. The issue of suicide among her police colleagues was obvious to her.

The goal of STAR is to get officers to talk about issues without fear of stigma.

“Police officers will tend to open up to other police officers,” she says. STAR brings together cops to share personal and emotional concerns.

The group sessions are not intended as professional therapy. “But at least if you are talking, you are getting a foot in the door,” says Phillips. The idea is to present a friendly community for troubled officers, who can still perceive even the most well-intentioned official channels as obstacles.

Phillips believes that talking about her own struggle can help others. Her work is geared not only to police officers but also to the families, like hers, that have suffered the trauma of suicide.

“Every single person I meet, I will tell them Emily’s story. It opens up a taboo subject,” she says.

(From left) Chaplain Bob Montelongo, a deacon and a cop, stands with Officer Jason Font and Father Dan Brandt outside Guaranteed Rate Field in Chicago.

Cop-Chaplain: ‘One Is Too Many’

Robert Montelongo, another Chicago police officer, supports Phillips’ efforts. Suicide prevention is a team effort that has to involve everyone, including cops who are not personally affected but can see the issue emerging in the lives of their fellow officers, he says.

Montelongo, 22 years a cop, is also a deacon for the Archdiocese of Chicago and now serves as a police chaplain. Because of the size of the department, he has seen a number of suicides among fellow officers.

“One is just too many,” says Montelongo, noting that he is sometimes one of the first on the scene and is expected to offer consolation to both fellow cops and families. He has knelt over and blessed the bodies of suicide cop victims.

Why are cops vulnerable? He points to the nature of the job. Every day, cops deal with the worst days that others experience. It can be wearing.

“You see the horrible things that happen in the world,” he says. Police are on the front lines of social disorder, especially in a city like Chicago, which has one of the nation’s highest murder rates.

Montelongo wears three uniforms on the job: civilian office attire, a police uniform, and the clericals of a deacon. These roles have much in common, says Montelongo, who compares being a police officer to a religious calling. “We are called to a vocation to go out and help others, to put it on your shoulders. It’s the call of a police officer.”

In many ways, his work with survivors of cop suicide is a ministry of presence. There are no preplanned magic words. When responding to such a call, Montelongo will pull over and say a prayer that he can bring the healing of the Holy Spirit to the scene, whether on the job or at the police officer’s home.

For Catholics, religious concerns often emerge when dealing with the suicide of a fellow officer or family member.

Some Catholic police families find little solace in their religion, which once condemned the act of suicide as contrary to God’s law. But in more recent times pastoral leaders emphasize that no one in this world can judge the culpability of a suffering victim. The Catechism of the Catholic Church states, “Grave psychological disturbances, anguish, or grave fear of hardship, suffering, or torture can diminish the responsibility of the one committing suicide” (2282).

Montelongo communicates to grieving families and friends that their loved one suffered from an illness, like those who die from cancer. It is a battle that could not be overcome, much like a physical illness.

Prevention is accomplished through supportive environments for all.

“The greatest thing we can do is to get people to talk to us,” he says. Montelongo spent many years on the street, including a stint on bicycle patrol. It helps his credibility to have a vocation as both a Catholic cleric and a police officer.

“I’ve done what they’ve done. It means a lot. They’ll use police lingo that I will understand,” he says, something a civilian would have trouble comprehending.

For example, cops at the scene of great tragedies often maintain a cool demeanor, appearing to the outsider as oblivious to the carnage that surrounds them. They may use language that can seem insensitive, for example, referring to a corpse as a “stiff.” But Montelongo knows it is part of the job, a way to rise above exposure to horror.

The civilian world can help by providing emotional and spiritual support for cops, he says. At St. Gabriel Church in the Canaryville neighborhood of Chicago, parishioners regularly pray the rosary for police officers. It is a quiet act, but appreciated.

“We need to have that,” says Montelongo, who notes that officers feel the sting of volatile opposition to the police, which has at times been a part of life in Chicago and other major cities.

In many police departments, there is a long tradition of Catholic involvement.

For survivors, faith in a loving God is one way to move toward acceptance of a tragedy and healing, says Phillips, a member of St. Barbara Parish in Chicago. “I can’t change it, ” she says of her experience with her daughter. “I give it to God and let him take care of it.”

For Cahill, urging police officers to seek help is one way he works through the issues surrounding his son’s death. He also receives spiritual direction from an 85-year-old Jesuit priest, whom he respects for his wisdom and counsel. In his book, he describes hearing his son’s voice on occasion.

He quotes the spiritual writer Father Ron Rolheiser that God’s love, unlike ours, can go through locked doors, a thought that offers him solace.