An Islamic tradition sheds light on our own season of repentance.

John Dunne, longtime theology professor, writer, and campus legend at the University of Notre Dame, wrote often and well about “passing over” to another’s viewpoint, culture, or religion and then “passing back” to one’s own with greater understanding and deeper compassion. It’s an imaginative process that can move a person from hostility to tolerance to respect, and from isolation to community, an experience of intellect and heart Dunne called “the spiritual adventure of our time.”

I’d like to share a personal experience of “passing over” to another religious tradition and “passing back” to my own, enriched yet humbled—a spiritual adventure I trust you’ll find interesting and suggestive of ways Christians and Muslims might better appreciate the shared mystical origin of both religions.

Adventures are for adults as well as kids, I’ve learned, and are times for trying on new ways of thinking and living, for testing and learning, for change and growth.

Most Catholics and other Christians who come from liturgical traditions know what Lent is. Quiz them and they’ll likely tell you it’s a once-a-year period of penance when they’re encouraged to give stuff up, pray more, increase their almsgiving, and perform more acts of charity.

Similar, Yet Different

Lent has admittedly lost some of its former penitential punch, but, despite changes in external observance, it remains for many a season for practicing the heartfelt reformation of life that the Gospels call repentance. “To me, it’s when you pray and fast and repent for having taken crooked roads, the ones that take you away from God,” is how my friend Alaa described it.

He’s a Syrian native whose wife comes from Islam’s holy city of Mecca, and he was talking about Ramadan, not Lent. But after we talked about Lent, he admitted the two seasons sounded similar. And they should.

Both are similar, yet distinctive, ways two religions practice our spiritual instinct for remembrance and repentance, abandoning crooked roads in favor of straight ones, and allowing God to touch hard hearts, adventures that always come as God’s gifts.

The call to repentance in Christianity and Islam is due in part to their shared identity as “Abrahamic religions.” Together with Judaism, Christianity and Islam trace their origins to the transformative mystical experience and subsequent religious quest of Abraham, a desert wanderer who appears in Genesis, the Bible’s first book, and in the Koran, Islam’s holy book that Muslims believe God revealed to Mohammed, Islam’s major prophet.

Abraham was a monotheist, a believer in one rather than many gods, a theological perspective that, as tame as it seems today, signaled a revolutionary turn in the history of religions. Not only is Abraham in the Koran, but Jesus and Mary, his mother, are there, too. Muslims consider Jesus a prophet and also hold Mary in high regard. That’s why most Muslims know more about Christianity than Christians know about Islam. On the other hand, few Muslims know about Lent, but most Christians have at least heard of Ramadan.

What most Christians know about Ramadan—that it lasts a month and involves fasting—and about Islam comes from popular media, sources notorious for highlighting conflicts and exaggerating differences between religions rather than pointing out what they have in common or how they might complement each other. My “passing over” helped me see what the two religions have in common, and my “passing back” forced me to confront the deep differences between them.

Although I had flirted with reading the Koran for a long time, it was only in June 2014 that, either by grace or chance, I finally did something about it, by undertaking my adventure of “passing over.” That’s when I saw a notice in a church bulletin about a local mosque that was inviting Christians to join Muslims for iftar, the daily evening meal that breaks the fast during Ramadan. After I read the notice, I was eager not only to read the Koran, but also to observe Ramadan.

Since it started in a week, I quickly bought a copy of the Koran, and read about Islam and Ramadan, mainly to see what it would require of me. I was no religious malcontent shopping for a new religion; I just had a hunch that Ramadan would let me look at repentance with fresh eyes and help me gain a deeper appreciation of the shared spirituality that unites the Abrahamic religions.

Lessons of Ramadan

Islam has “five pillars” or core beliefs that function for Muslims the way the Creed—a statement of the “pillars” of Christian belief—does for Christians. Observing Ramadan is one pillar, the others being faith, daily prayer, almsgiving, and pilgrimage. Devout Muslims pray five times each day, a style of prayer similar to the Liturgy of the Hours in the Christian tradition. Another pillar for Muslims is hajj, a once-in-a-lifetime pilgrimage to Mecca all Muslims are urged to make.

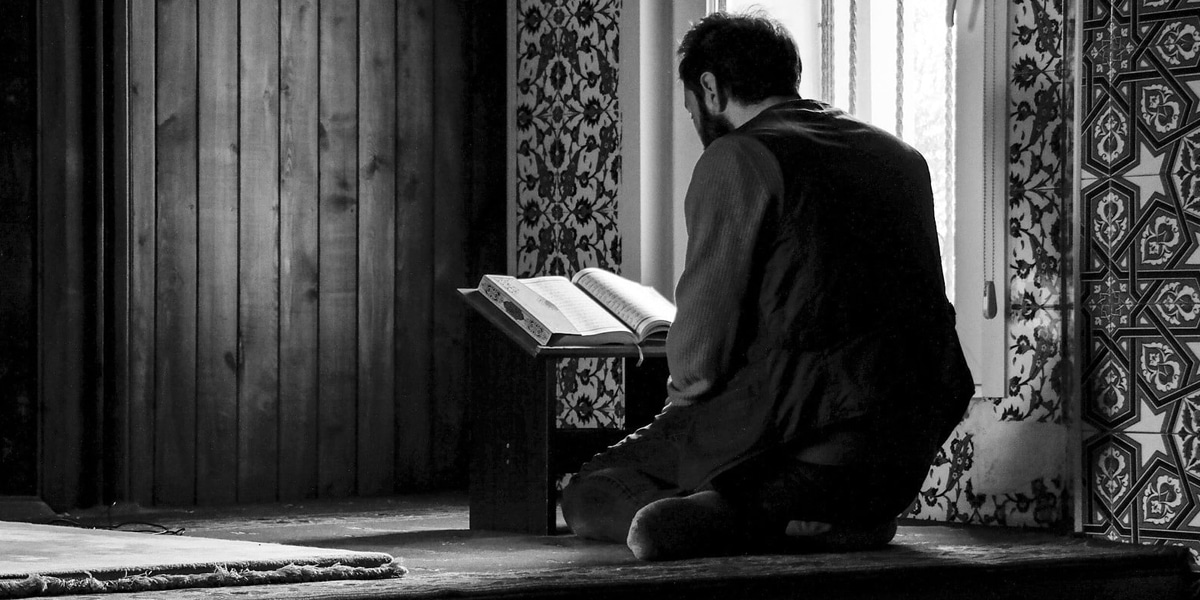

Muslims fast from food and water from sunrise until sunset during Ramadan, read the entire Koran, and increase their almsgiving— a practice that underscores Islam’s fundamental commitment to social justice, a concern that resonates deeply with the witness of Pope Francis. So when Ramadan started, I also fasted (something that seemed impossible when I thought about it, but proved less ominous when I did it). I gave lots of clothes to charity, attended Friday prayers in a local mosque, read the entire Koran, and joined Muslims for iftar and informal spiritual conversation each week.

I prayed during Ramadan with the first seven verses of the Koran, the Al-Fatiha, a brief poetic summary of Islamic faith. “In the name of God, Most Compassionate, Most Merciful,” is how it starts, an invocation that immediately highlights Islam’s belief in one utterly transcendent God, who is revealed to believers most directly in compassion and mercy. Unlike the God of the Bible, the God of the Koran knows nothing of incarnation or trinity. But since the Trinity summarizes Christian belief, many start our prayer, “In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.”

The Al-Fatiha then begs God to keep the believer on the “straight” path of fidelity, far from infidelity, idolatry, and self-seeking. Wandering from and looking for the straight road is an image that appears in the sacred texts of all the Abrahamic religions and also serves as a central image of the spiritual discernment required to come to religious maturity.

A Renewed Faith

Lent and Ramadan are not only seasons of repentance but are also times of remembrance, something that means more than paying casual attention to past events. Instead, religious memory brings “faithtime” to mind, allowing a believer to enter into the religion’s original formative experiences through the power of the religious imagination and ritual.

Lent’s 40 days remind Christians of the 40 years the Hebrews spent in the desert, and the 40 days Jesus was in the desert being tempted, changed, and prepared for the saving demands of his mission. Observing Lent allows us to enter into these times, making their stories of exploration and discovery our own.

When Muslims observe Ramadan, they remember when God revealed the Koran to Mohammed. In doing so, they don’t just pay lip service to this past event, but they remember how God continues to reveal words of compassion and mercy to them today. Ramadan is how Muslims keep repentance alive in fasting, prayer, and almsgiving. They fast to remember and respond to the hungers and thirsts of the less fortunate and of their own hearts, doing so with a repentant spirit, one that leads them back to the straight road and keeps them on their pilgrimage toward God.

Ramadan also helped me see how the Abrahamic religions are “religions of the road,” a theological principle— moving toward a destination rather than repeating mythic cycles—that, like monotheism, signaled another revolution in how religions imagine themselves.

As a result, Abrahamic believers see themselves on a pilgrimage in time, moving toward a personal and social end point traditionally described as eschatological, an ultimate drama in which the mysteries of life and death, reward and punishment, fulfillment or destruction, and final consolation or desolation get played out. The choices made “on the road” have eternal individual and communal consequences for believers.

This insight let me see how differently Christians and Muslims imagine the nature of God and God’s relationship to the world and history. As Ramadan ended, I noted in my journal, “In the end, I’m just not otherworldly enough to be a Muslim.” That’s when I began to see how a religion of prophecy like Islam and a religion of incarnation like Christianity are different, yet complementary. This insight signaled the beginning of my “passing back” to my own religious imagination and tradition.

Islam worships one God existing beyond human history, while Christianity worships one God who is also incarnated in human history. For Muslims, this life and human history prepare us for the next life, while Christians, because of incarnation, see the world and history as holy and significant, not just as a testing ground for heavenly bliss.

While Muslims see Mohammed as a human being like everybody else, Christians consider Jesus not only a prophet but a divine prophet. In him and in the power of the Holy Spirit, the Trinity of God meets and transcends human experience and history.

Christian theologians describe this back and forth between time and eternity, history and eschatology, as the living tension between the transcendence (beyond human experience) and the immanence (within human experience) of God. Is God involved, removed, or both? Is our religious pilgrimage in this world only toward God, or, as Christians would describe it, is it also through, with, and in the God we see incarnated in Jesus and animated in the Holy Spirit?

Ramadan offered me a deeper appreciation of my belief in God’s activity in creation and evolution, history and eschatology, and incarnation as well as transcendence that led me to conclude that I wasn’t otherworldly enough to ever be Muslim.

I also started to see how Christianity and Islam need each to balance the potentially deadly and exaggerated, hostile and isolating fundamentalist extremes lurking on the peripheries of both religions. Christians need Muslims to remind them of the transcendent dimension of our experience of God, and Christians, because of our belief in incarnation, can help Muslims keep their feet planted firmly on the earth. That way our religions can do more than compete with each other: they can actually complement and correct each other.

Lesson Learned

My adventure of “passing over” and “passing back” happened because of a notice a mosque placed in a Christian church bulletin. I occasionally wonder what could happen if Christian churches took the initiative to invite Muslims to share Lent with them. It could lead to conversation and prayer together, a way of sharing our seasons of repentance. One Catholic community I know of sponsors soup suppers and prayers every Friday evening during Lent; events offered by other Christian communities could provide productive occasions for conversation and prayer.

What my “passing over” to Ramadan and “passing back” taught me, more than anything else, is that while doctrine and ideology often divide, service and shared spirituality are opportunities for a unity that can respect differences without being incapacitated by them—a gift our divided world sorely needs today.

Read: 10 Things to Know about Islam