For centuries we have reflected on the seven last words of Christ during Lent, but few people have spent much time considering his earliest words in the Gospels at the same time. It might seem like these are two very different things reserved for two different liturgical seasons: the beginning is left for Advent and Christmas, while the ending is for Lent and Holy Week. But these two seemingly distinct sets of words are significantly more intertwined than we would usually imagine.

The Words of a Child

Take, for instance, the first three times that Jesus speaks in Luke’s account of the Gospel. As we read at the end of the last chapter, Jesus’s first words at the age of twelve bespeak a closeness to and intimacy with God that is articulated in terms of parental relationship; Jesus calls God “Father” (Luke 2:49). This is echoed throughout the story of Jesus’s ministry and preaching, and repeated finally from the cross.

While we might initially think of Jesus’s youthful response as that of a precocious twelve-year-old (a perspective many parents must certainly appreciate), there is a profound truth conveyed here about who God is and who we are. Jesus expresses to us, in our own human terms and from his own human experience, what the relationship is like between God and us. It is something very close, as close as that between a parent and child.

Jesus, God as one like us, not only says but lives what was foretold in the book of the prophet Isaiah: “As a mother comforts her child, so I will comfort you” (Isaiah 66:13).

Like a mother or like a father, God knows us better than we know ourselves. This relationship is described elsewhere in Scripture as even more intimate than that between a mother and child, because God has said through the prophets that, “Before I formed you in the womb I knew you, and before you were born I consecrated you” (Jeremiah 1:5). To call God “Father” (or “Mother,” for that matter) is a powerful statement that is for us both an address and a profession of faith.

The Words of Temptation

The next time we hear Jesus speak in Luke’s Gospel is when he is tempted in the desert. In response to each of the three classic temptations that the devil places before him, Jesus responds by quoting Scripture. “It is written,” is the common introduction for his retort, a detail that can seem insignificant, but in fact bears an important implication. It is not Jesus alone—or each of us in our own experiences of temptation—that is the arbiter of what is right or wrong; rather, it is God through divine revelation that has made known to humanity the path we should walk.

Scripture, the historical medium of God’s revelation, offers us a concrete resource in coming to form our worldviews and inform our consciences.

What Jesus lays out for us in these early words in the Gospel is the importance of embracing our collective story, the narrative of God disclosing who God is over time and through the people, times, places, and events conveyed in the Hebrew Scriptures and the New Testament. Whereas Jesus, the Word made flesh, could easily have spoken some original words to combat the temptations in the desert, he instead draws from the collective story of God’s chosen people, a story that he restates as his own and invites us to do the same. To speak the words of Scripture and make them our own is a powerful statement about our identity and worldview.

The Words in the Synagogue

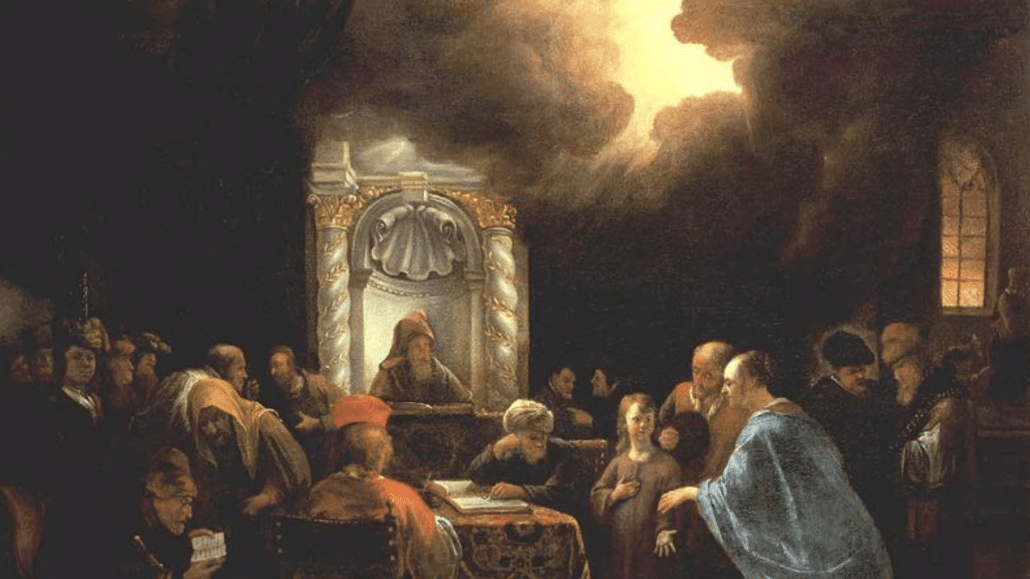

The third time we hear Jesus speak in the Gospel according to Luke is after he has spent the forty days and nights in the desert fasting, praying, and preparing for the start of his public ministry. Luke tells us that Jesus was then “filled with the power of the Spirit” and returned to Galilee to teach in the synagogues (Luke 4:14–15). The next thing we read is one such instance when Jesus arrived back at his hometown of Nazareth and entered the synagogue on the Sabbath.

He stood up to read, and the scroll of the prophet Isaiah was given to him. He unrolled the scroll and found the place where it was written: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.” And he rolled up the scroll, gave it back to the attendant, and sat down. The eyes of all in the synagogue were fixed on him. Then he began to say to them, “Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing” (Luke 4:16–21).

In these early words, long before the cross, we see the earliest inkling of what will eventually lead the religious and civil leaders of his time to crucify Jesus, as well as a summary of what his mission (and by virtue of our baptism, our mission) is all about: social justice.

Words of Justice

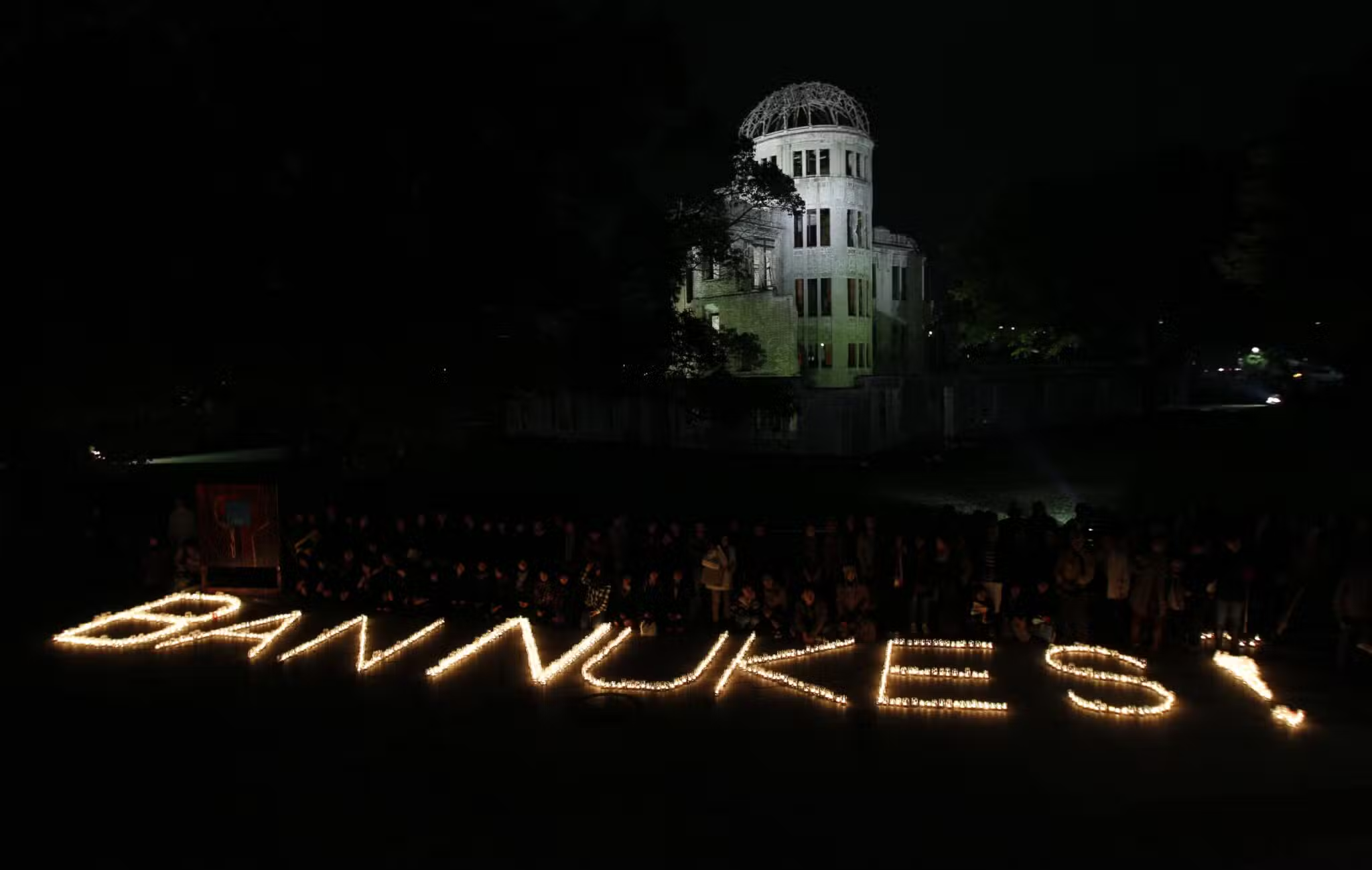

What Jesus has been anointed (which in Greek is Christos) to do is proclaim the in-breaking of the kingdom of God, which is seen when justice and mercy reign in our world. Those who are bound by the shackles of injustice, discrimination, marginalization, oppression, fear, and violence are captives that are set free, prisoners that are granted release by God’s love and mercy. Conversely, those who are blinded by the greed, selfishness, lust for power, desire for wealth, obsession with control, are granted new sight so that they can see the world as it really is, which means to see the world as God sees it and to change one’s life so as to live as a true follower of Christ.

Those who have a vested interest in maintaining the status quo, who are concerned about preserving their own power and control, are likely to find Jesus’s proclamation of his mission threatening. It does not take much imagination to see how such a worldview could get someone crucified, for speaking out for and working on behalf of the oppressed necessarily draws undesired attention to the oppressors. To speak the words of justice, mercy, and peace is a powerful statement about how we are to live in the world.

These three first words of Christ reveal to us much about what it means to be Christian and helps to place what happens on the cross on Good Friday within a broader context. When we fixate on the end without taking into account the beginning, we take the words of the Lord out of context. Just as these first words from Luke’s account of the Gospel present us with profound insights about our intimacy with God, the centrality of Scripture in forming our identity, and that the way of Christian living is to work for social justice, the Seven Last Words from the cross reiterate the beginning of the Lord’s ministry.

Words of Love and Suffering

These first words, like those that come from the cross, reflect the two sides of passion: love and suffering. To have an intimate relationship with God, to make the narrative of Scripture our own story, and to work for social justice in our world requires the surrender of control necessary for love and means that our loving vulnerability and openness will, at times, lead to suffering.

Our love and suffering as Christian disciples, like the Lord’s on the cross, does not happen in vain. As the Franciscan scholar Zachary Hayes stated so clearly, “We become like what we love,” and that transformation recasts the categories of our ordinary experience into something else, something greater, something more than what we had originally expected. This is not to deny the real pain, loss, and trauma that can accompany suffering and our involuntary loss of control, but it does suggest that the meaning of human experience is deeper and more significant than we generally think (or that our popular culture would have us think).

This is what is at the heart of reflecting on the Seven Last Words of Christ. This, too, is what considering the first words of Christ means for us. Beneath the surface of a few sentences stand profound truths that are not merely historical snippets for us to admire millennia later in our annual recounting of that Good Friday afternoon. Instead, there is a richness to God’s revelation, to the divine self-disclosure that takes place in the words passed on to us from the mouth of the Word-made-flesh.

Like Francis of Assisi, we too can be transformed by the power of love and embrace the call to Christian discipleship with passion. The task at hand is to see that the Word continues to call us to move beyond ourselves, to enter into an evermore intimate relationship with God, to make God’s story our story, to work for justice and peace in our world, and to embrace the love and suffering that comes with following Christ.

1 thought on “The First Words of Christ”

Good morning Father

I came upon your blog when thinking that if in Ps 2 we hear God’s voice for the first time (within The Psalter – according to Jon Delhousaye) then where do we hear Jesus’ first words?

Reading through your article, I find so much to meditate and so much that truly gives me guidance in how to live in a world full of “raging kings” overwhelming disasters and human suffering…. May we all become the LOVE we were called to love.

Thank you for your thoughtful and inspired words. Isabel

Comments are closed.