In celebration of their holiness, virtue, and influence, here is a Top Ten list of saints who substantially shaped the face of the Catholic Church.

From the start, we should also acknowledge the nameless men, women, and children in the pews who became increasingly central to the life of the Church in the last 1,000 years—not to mention the great impact of the faithful who built the Church in its first millennium.

Here’s my personal attempt to list the Top Ten Catholic movers and shakers of the second millennium.

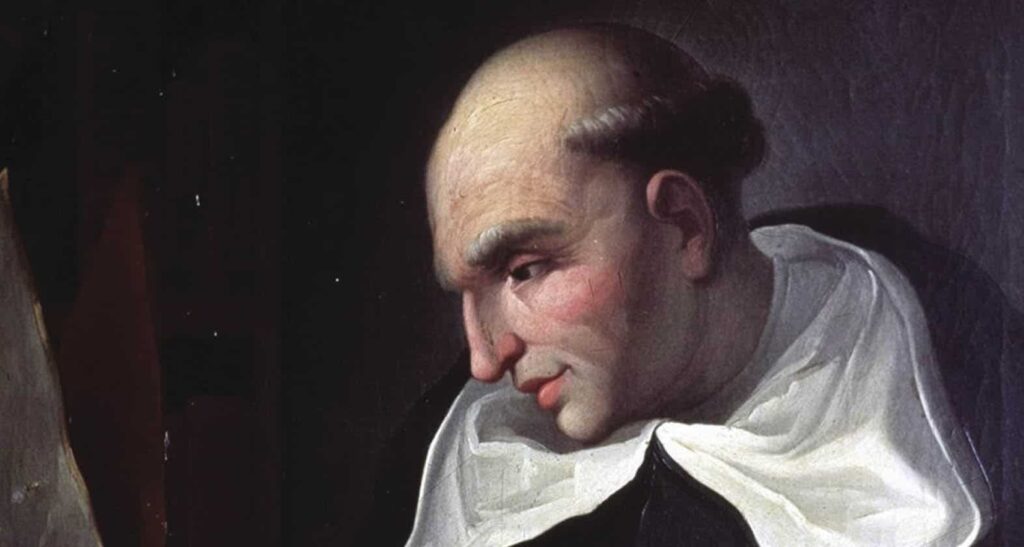

Gregory VII rises at the dawn of the millennium like a giant on whose broad shoulders all later popes stand. He was trying to accomplish several goals. First, he wanted to get the Church out from under the authority of the secular powers so bishops, abbots and even popes could be selected freely. Second, he wanted to establish the papacy as the ultimate, unquestioned authority in the Church and the world. Third, he wanted to improve the moral behavior of the clergy.

Gregory pursued these goals like the proverbial avenging angel, fiercely using his spiritual and temporal power. His best friend called him “a holy Satan” and in his letters we can hear why.

“To Bishop Jaromir of Prague, greeting and apostolic benediction,” the pope wrote to a bishop, “even though he does not deserve it.”

Gregory’s actions touched the Church from top to bottom: He excommunicated Emperor Henry IV, the most powerful emperor in Europe, while he worked to make celibacy the absolute rule for every priest. He forbade anyone to buy or sell a Church office, a crime called simony, and tried to remove bishops who fought his reforms or who had been put into office by local kings or nobles.

Gregory VII so changed the papacy that his efforts were not a reform but rather a revolution. He began to organize the papacy as a powerful monarchy with all the power, prestige and pomp of competing authorities. The popes who followed him during the Middle Ages were administrators and canon lawyers like Innocent III (pope, 1198-1216), who built the bureaucracy we think of when we say “the Vatican” or “the college of cardinals” today.

But papal revolution had a price: This bureaucracy often grew so worldly that the papacy itself became a target for reform in the middle of the second millennium of Christianity. Still, Gregory VII helped set the standard for moral leadership that has particularly been exercised by the popes of the 20th century.

St. Francis of Assisi (1182-1226)

Francis personified a medieval spirituality that was as emotion-filled as Gregory VII’s papal monarchy was programmatic. But we tend to take Francis out of his historical place—that is, we see him as a timeless saint who speaks to all centuries and countries. And while that is true, we can appreciate Francis and his legacy more if we place him in his own time.

Francis ministered to the poor in ghettos because that’s where the poor people were. Europe was undergoing significant economic and population growth at this time that made cities the cutting-edge spots in society. Whenever the rich got richer, the poor got poorer. Francis had dedicated his life to following Christ’s example as closely as possible by clothing the naked, feeding the hungry and sheltering the homeless. He knew that whenever he did this for the least of Christ’s brothers and sisters, he did this for Christ himself, a scriptural ideal that was very popular for medieval Christians who, like Francis, tried literally to imitate Jesus’ life.

When most people thought of Jesus in the Middle Ages, they thought in terms of the human Jesus who walked, ate, cried, suffered and did all the other things humans do. This idea of Jesus represented a change, since for the better part of the first millennium of Christianity the emphasis was on Jesus’ divinity because so many heresies claimed that Jesus was either a superman or divine—but not human.

That heresy settled, and in large part because of Francis’ example, Christians after the year 1000 increasingly began to discover and identify with a Jesus that was like them in all things but sin. Francis conformed his life so closely to Christ’s that he was known as the alter Christus—Latin for “another Christ.”

Francis left a legacy of trying to walk in the footsteps of a familiar Jesus in the circumstances of our everyday lives, an apostolic life that combines prayer and action.

His contemporary St. Clare of Assisi (1194-1253) established the Poor Clares, adapting Francis’ spirituality for women. St. Bonaventure (c. 1221-1274) organized Francis’ vision and shaped the Franciscan Order as its manager and mystical theologian. Meanwhile, St. Dominic (1170-1221) founded the Dominican Order, another group of cutting-edge mendicants, who fought heresy and spread the faith through their teaching and preaching missions.

The influence of the poor man of Assisi is so great that Pope Francis, in the hopes of keeping the poor ever present in his mind, chose his name accordingly.

St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274)

More than any other theologian, Aquinas shaped how Catholics talk about theology. That statement remains true, even though many theologians rejected his scholastic method as being too formal and not practical enough in the centuries after he died. But the fact that Aquinas became a hero to some and a roadblock to others only solidifies his place as the greatest thinker Christianity has ever produced.

Aquinas was a university professor and Dominican priest who organized the study of theology in the Summa Theologiae, a summary organized by topic. He didn’t invent this method, but many judge him to be the best at it. His great achievement lay in taking all sides of a theological question—like “Can it be demonstrated that God exists?”, but never “How many angels can dance on the head of a pin?”—and reconciling them into one formulaic, authoritative, standard theology text.

His scholastic method of pursuing answers by very carefully laying down questions was revived in the 19th century and influenced a new generation of scholars who, as in his own lifetime, either followed in his tradition or disagreed and tried to come up with alternatives.

But even Aquinas knew he didn’t have all the answers. Shortly before he died, he had a vision during Mass that made him stop writing. Compared to what he’d just experienced, he told his friends, all of his writings were just straw. Even for Aquinas, Christianity was a faith seeking understanding.

St. Catherine of Siena (1347-1380)

The late Middle Ages saw institutional chaos with the papacy’s move from Rome to Avignon (1305-1378) followed by the Great Schism, when two and then three popes fought for authority (1378-1417). A century later Protestants and Catholics split.

But during this period there is a great flourishing of female mysticism. We’ll let one faithful woman stand for many others who took an ever more active role in the Church as the millennium advanced.

Catherine was a Dominican tertiary who gathered a spiritual family of men and women, which raised some eyebrows, and refused either to stay in one place or to keep her voice down. Catherine resisted the accepted course of marriage and motherhood, on the one hand, or a nun’s veil, on the other. She chose to live an active and prayerful life outside a convent’s walls following the model of the Dominicans.

She left nearly 400 letters, including several strong ones to popes, fairly warning them to use their power and authority wisely. Her cries for reform pressed the popes to leave Avignon, where they had been living luxuriously, and to return home to Rome. Catherine had visions throughout her life, including what she described as a mystical marriage with God and union with Christ’s suffering on the cross. She set these experiences and others down in a dialogue between herself and God.

Bartolomé de Las Casas (1474-1566)

Dead center in the second millennium, Christianity crossed the Atlantic with Columbus. But the story of the first Christian missions is marked by the cruel treatment of indigenous people whom Columbus incorrectly called “Indians.” “How easy it would be to convert these people,” Columbus reported back to Europe, adding ominously, “and to make them work for us.”

One voice in particular was raised against this treatment.

Las Casas’s father sailed with Columbus on his second voyage and returned with an Indian slave for his son. The younger Las Casas went to present-day Cuba in 1502 where he owned land and slaves despite his later ordination to the priesthood. In 1514 he saw with new eyes the Indians’ slavery.

Named “Protector of the Indians,” he shuttled between Spain and the Americas working against treatment that included slavery, torture and rape. He argued Indians were human beings with the same equality and natural rights as white Europeans; they were not inferiors, animals or adult-sized children.

Las Casas was still bound by the biases of his age: At one time he approved of black slavery, but later recanted. He joined the Dominicans and served as a bishop in Mexico where his own people called him a lunatic and tried to hang him. He was behind the New Laws of 1542-1543 outlawing slavery, at least on paper. His most important attack was Brief Relation of the Destruction of the Indies that produced the infamous “black legend” about Spanish treatment of the Indians, which probably exaggerated a harsh reality.

His efforts remind us that it took some time for Christianity really to live the ideal that all Christians in an expanding world are equal in God’s eyes.

St. Ignatius Loyola (1491-1556)

Ignatius was raised to be a chivalrous courtier and soldier, but that changed when his legs were shattered by a cannonball during a battle when he was about 30. During his recovery, he read about the lives of Christ and the saints. He transferred his romantic sense of mission to the Church and, because he wasn’t educated in Latin, the language of theology, he squeezed himself into the little chairs at a local grammar school and began with amo, amas, amat….

From these baby steps came a doctorate in theology and the idea of a new order, the Society of Jesus. What made the Jesuits unique was the way they put themselves at the Church’s disposal, adding a fourth vow to poverty, chastity and obedience—to go out and do whatever job the pope assigned them.

So while the Jesuits were not founded to fight the Protestant challenges or to establish schools, these naturally became major activities since they were the tasks at hand.

Ignatius was a rare combination: a contemplative in action, both a visionary and an administrator who prayed as hard as he worked. He left more than 6,000 letters giving detailed instructions and encouragement.

From his experiences as a spiritual director and mystic who experienced visions, Ignatius drew on his own prayer journal to leave the Spiritual Exercises. Like Teresa of Avila’s Interior Castle, which came out of the same Spanish mystical tradition, the Exercises teach that prayer is a journey with days of consolation and desolation. What is most important is keeping on a steady course through a daily examination of conscience that allows us to discern which thoughts, or “spirits,” we should follow in order to do all things for the greater glory of God.

St. Teresa of Avila (1515-1582)

St. Teresa was too bold for many Christians, especially those in authority. As a female mystic, she was distrusted.

A member of the Carmelites for 20 years in a very comfortable convent, Teresa was treated with suspicion and opposition by members of her own Order who resisted her reforms once she had a conversion experience.

Her own spiritual life, especially as she described it in Interior Castle, was unsteady and marked by highs and lows, ecstatic union with God and silence so strong she wondered if God was listening anymore.

She finally achieved a reform of the Carmelites by establishing a more austere branch that went back to poverty and simplicity, although bishops and kings fought her changes. Teresa of Avila, with Catherine of Siena, was declared a Doctor of the Church in 1970.

Ours is a time of turmoil, a time of reform, and a time of liberation. Modern women have in Teresa a challenging example. Promoters of renewal, promoters of prayer, all have in Teresa a woman to reckon with, one whom they can admire and imitate.

St. Charles Borromeo (1538-1584)

As the Catholic Church responded to the Protestant challenges, bishops were charged with leading the way in their dioceses as the key agents of reform and the chief shepherds of their people. The model bishop was Borromeo, who became archbishop of Milan at the age of only 28. He had worked hard at the Council of Trent and afterward to reform the Catholic catechism, missal, breviary and liturgy, as well as to help establish seminaries.

At first he seemed an unlikely candidate for bishop: He was a cardinal living in luxury long before he was a priest and bishop, but in Milan he always dressed and signed his name as bishop, not cardinal.

In Milan, Borromeo was known for training the clergy in mind and heart so they could be caring and educated pastors, for visiting parishes, for reorganizing the administration of his diocese and for his early version of religion classes for children on Sunday mornings. Often asked for advice by other bishops, he left a huge paper trail for them and their priests to follow. He wrote in Italian so his ideas would have an even wider circulation.

He was so zealous in pushing his reforms that twice someone tried to kill him. As the Church continues to look to the bishops to implement reforms after Vatican II, the innovative and energetic figure of Borromeo remains as the ideal to be adapted to changing times.

St. Elizabeth Seton (1774-1821)

Despite caricatures of the occasional ruler-slamming sister used to stain nuns as the most maligned group in the Church, it remains true that Catholic schools are the envy of nearly every urban public school system. Where would the Church be today without orders of teaching nuns who created an educational program still copied throughout the world?

Perhaps the most familiar to Americans is Mother Seton, the first native-born American to be canonized. Widowed before she was 30, she converted to Catholicism from the Episcopal Church and established the American Sisters of Charity, who dedicated themselves particularly to educating the poor. Mother Seton brought to the United States a vocation that actually began with the first teaching order of nuns, the Ursulines, established by St. Angela Merici (1470-1540).

Merici’s concern was especially to train girls who would become responsible wives and mothers, creating in their homes the domestic churches on which the Catholic Church stands. She was soon followed by St. Louise de Marillac (1591-1660) who, with St. Vincent de Paul (1580-1660), founded the Daughters of Charity (known also as the Sisters of Charity).

Elizabeth Seton moved women out of the cloister and into the world where they taught, ran orphanages and worked as nurses in hospitals and even on battlefields. Mother Seton’s order, plus all of the many teaching orders, brought the children of immigrants (and even some immigrants themselves) from illiteracy to college and beyond, sometimes in a single generation. On their classroom drills and discipline were built careers in every profession.

Perhaps more importantly, their examples of corporal and spiritual works of mercy in daily life, far from high Church and civil politics, left a legacy of service for their pupils who became leaders of society, spouses and parents.

These nuns arguably had a greater, more intimate impact on the Catholic family than any other group in the Church.

St. John Henry Newman (1801-1890)

Catholicism didn’t start updating with Vatican II’s aggiornamento. The Church is always growing, but more directly related to Vatican II’s reforms were events and ideas that began to bubble about 150 years before Pope John XXIII called the Council. Newman was a key figure in rejuvenating Catholicism. He was so forward-looking that some call Vatican II “Newman’s Council.”

Newman was an Anglican priest who gradually moved toward the Catholic Church, joined, became a Catholic priest and was eventually named a cardinal. Newman was a scholar and a preacher who understood that the Christian life was a series of conversions and attempts to live the faith more deeply each day, even as the world changed daily.

One of his lasting achievements was looking at the study of theology in terms of development. Doctrine doesn’t change, Newman wrote, but our understanding of fundamental truths and mysteries does develop. We can explain the faith in new and better ways the more we study the past. But new ideas and words should be measured against the past to see if they are authentic and faithful to the Church’s tradition, Newman said.

Another legacy was his loud call for an educated, involved laity. In what amounts to a shout for action, Newman nearly demands, “I want a laity, not arrogant, not rash in speech, not disputatious, but men who know their religion, who enter into it, who know just where they stand, who know what they hold, and what they do not, who know their creed so well that they can give an account of it, who know so much of history that they can defend it. I want an intelligent, well-instructed laity.”

Though Newman may have been bound by the 19th century when he spoke of “men” here, laywomen as well as laymen have been living their vocations more and more as the Church is well into its third millennium.

This first appeared in the pages of St. Anthony Messenger.